วิกฤตโรฮิงญา

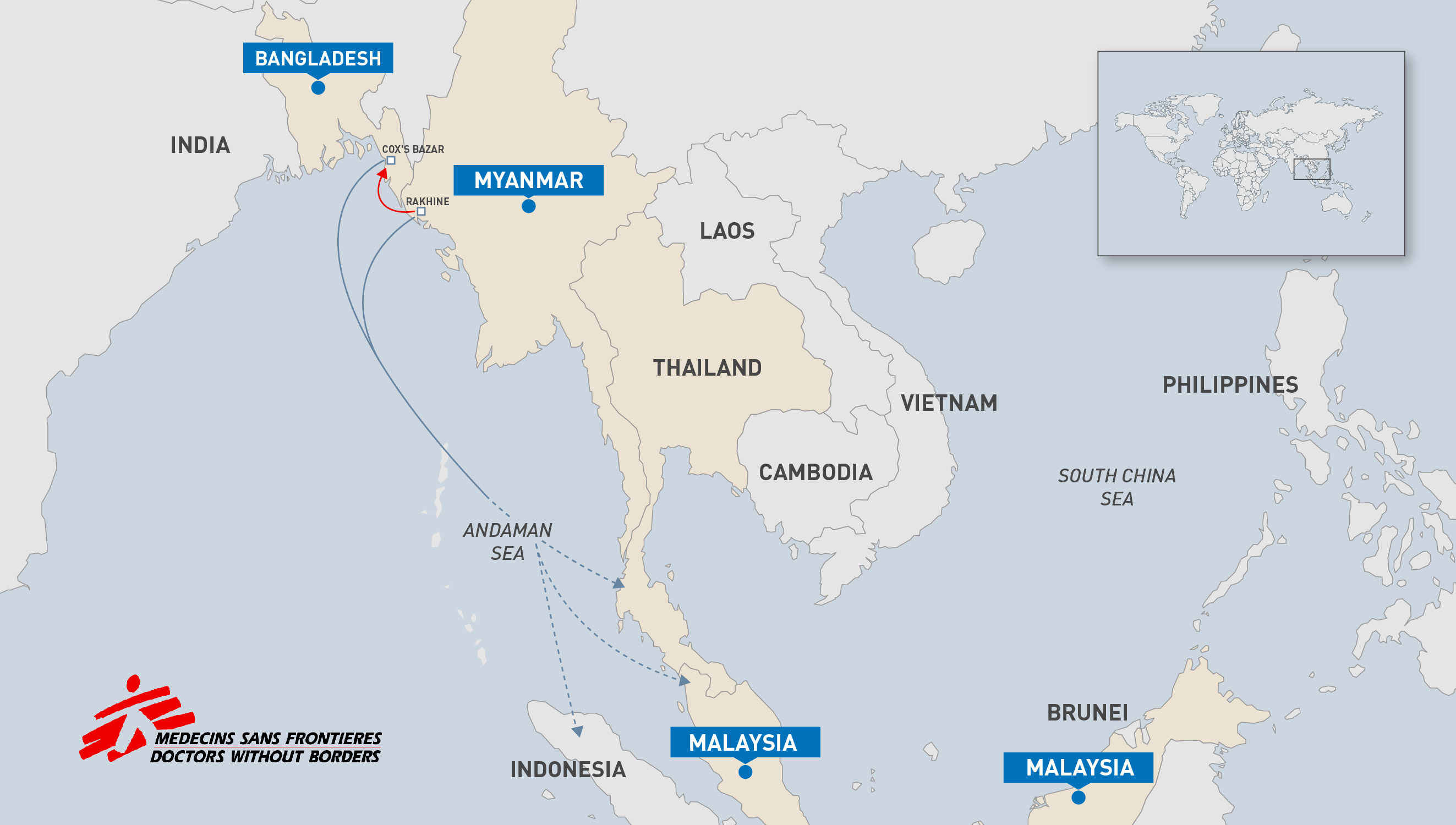

ไม่ว่าจะในประเทศเมียนมา บังกลาเทศ หรือมาเลเซีย องค์การฯ มีความกังวลเกี่ยวกับความเปราะบางและอนาคตที่กำลังหายไปของชุมชนโรฮิงญา

ข้อมูลล่าสุด

วิกฤตการณ์ด้านมนุษยธรรมในรัฐยะไข่ ประเทศเมียนมานั้นย่ำแย่ลง ความรุนแรงที่ยกระดับขึ้นส่งลงให้มีชาวโรฮิงญาจำนวนมากได้รับบาดเจ็บและต้องอพยพไปยังประเทศบังกลาเทศ ทีมงานขององค์การแพทย์ไร้พรมแดนในเมืองค็อกซ์ บาซาร์ รับตัวผู้บาดเจ็บอาการสาหัสจำนวน 39 ราย ซึ่งจำนวนมากเป็นผู้หญิงและเด็กเข้ารักษา ตัวเลขของผู้บาดเจ็บที่มากขึ้นสะท้อนสถานการณ์ที่ร้ายแรงในเมียนมา และผู้คนอีกมากที่ตกอยู่ใต้ความขัดแย้งที่ไร้ทางออก

บทความที่เกี่ยวข้อง

สำหรับชาวโรฮิงญา การแก้ไขปัญหาอย่างยั่งยืนและต่อเนื่องคือสิ่งจำเป็น ประชากรกลุ่มนี้ไม่อาจกลายเป็นบุคคลที่ถูกละเลยและลืมเลือน หรือเป็นเหยื่อของการดึงเชิงกันทางการเมืองระดับภูมิภาค

ประเทศพม่า (เมียนมาในปัจจุบัน) ได้รับอิสรภาพจากสหราชอาณาจักรในปี 2491 ภายใต้การก่อร่างสร้างประเทศขึ้นใหม่ ชาวโรฮิงญาเองก็ได้สัมผัสกับคำว่าความเสมอภาคเช่นกัน หากเรื่องราวกลับตาลปัตรในปี 2525 เมื่อชาวโรฮิงญาถูกริบสถานะพลเมืองและกลายเป็นบุคคลไร้รัฐในชั่วข้ามคืน

การเปลี่ยนแปลงอย่างฉับพลันดังกล่าวนำไปสู่ศตวรรษแห่งการประหัตประหารและข่มเหง ชาวโรฮิงญาถูกปฏิเสธสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐานและสถานะพลเมืองในเมียนมา โดยสถานการณ์มีการยกระดับในช่วงเดือนสิงหาคม 2560 เมือมีการยกระดับควานรุนแรงที่พรากชีวิตชาวโรฮิงญาและเด็กอย่างน้อย 6,700 ชีวิต รวมถึงบีบให้ผู้คนกว่า 600,000 รายต้องหลบหนีออกจากประเทศเมียนมา สำหรับคนที่ยังคงอาศัยอยู่ในประเทศก็ต้องเผชิญกับความเป็นจริงแสนโหดร้ายภายในค่ายผู้ลี้ภัย รัฐยะไข่ เนื่องจากบ้านเรือนของพวกเขาถูกทำลายอย่างสมบูรณ์

สำหรับกลุ่มคนที่เลือกอพยพและแสวงหาพื้นที่ลี้ภัย นั่นหมายถึงพวกเขาเลือกเดินบนเส้นทางแสนอันตรายทางบกหรือทะเล เพื่อส่งตัวเองไปยังประเทศอย่างบังกลาเทศ มาเลเซีย กัมพูชา ไทย และอินเดีย

มีชาวโรฮิงญาราว 2 ล้านชีวิตอาศัยอยู่ทั่วภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ มากกว่าครึ่งอาศัยอยู่ภายในรั้วค่ายผู้พลัดถิ่นที่ใหญ่ที่สุดในโลกอย่างค็อกซ์ บาซาร์ ประเทศบังกลาเทศ ขณะที่มีอีกกว่า 600,000 ชีวิตถูกจำกัดการใช้ชีวิตอยู่ในรัฐยะยไข่ การอาศัยอยู่ในภาวะแสนแร้นแค้นนั้นรวมถึงการจำกัดการเข้าถึงการศึกษา การทำงาน และความก้าวหน้าในชีวิต นอกจากนี้ยังมีการออกเงื่อนไขเพื่อตีกรอบการเดินทางออกจากชุมชนหรือค่าย หรือแม้ว่าจะหลบหนีไปตามมุมเมืองอื่นทั่วโลก พวกเขาก็กลายเป็นคนชายขอบในสังคม ที่ไม่ได้รับโอกาสในการศึกษ สิทธิในการทำงาน และต้องอยู่กับความหวาดผวาว่าอาจจะถูกจับกุมไม่ต่างกัน

ปัจจุบันมีชาวโรฮิงญาเพียง 1 ใน 5 ที่ยังคงอาศัยอยู่ในประเทศเมียนมา โดยเด็กเกิดใหม่เกือบทั้งหมดลืมตาบนพื้นที่อื่นนอกเหนือจากบ้านเกิดเมืองนอน ไร้เยื่อใยสายสัมพันธ์กับสาแหรกของตน การปฏิเสธสถานะพลเมืองหมายถึงการสูญเสียโอกาสในการได้รับพาสปอร์ต ส่งผลต่อให้การเดินทางข้ามประเทศนั่นเป็นเรื่องที่ผิดกฎหมายหรือเสี่ยงต่อการถูกคุมตัว เป็นเรื่องที่แสนเศร้าที่ต้องยอมรับว่าปัจจุบันชาวโรฮิงญาคือหนึ่งในกลุ่มคนที่มีสถานะเป็นคนไร้รัฐมากที่สุดในโลก ไม่ได้รับการคุ้มครองตามกฎหมาย ไร้อิสระเสรีและกลายเป็นคนชายขอบในสังคม ไร้โอกาสในการเข้าถึงบริการทางการแพทย์และการมีชีวิตที่เหมาะสม

อิสรภาพที่ถูกพรากไปทิ้งให้พวกเขาต้องจมอยู่ใต้ความทุกข์ทนที่ซ้ำซ้อน ถูกพรากสิทธิอันเสมอภาคอันพึงมีกลายเป็นคนไร้รัฐ และเป็นปัญหาฉุกเฉินที่ยังเรื้อรังอยู่

ชาวโรฮิงญาต้องการเห็นภาพอนาคตที่ชัดเจน การอาศัยอยู่ในพื้นที่พักพิงชั่วคราวคือการลดทอนศักดิ์ศรีความเป็นมนุษย์เอริค เองเกล ผู้ประสานงานโครงการ

ไทม์ไลน์ "วิกฤตโรฮิงญา"

รัฐบาลทหารของพม่าประกาศใช้พระราชบัญญัติคนเข้าเมืองฉบับฉุกเฉิน ซึ่งภายใต้กฎหมายฉบับดังกล่าว บังกลาเทศ จีน และอินเดีย ถูกลดสิทธิเนื่องจากถูกตีตราว่าเป็น "ชาวต่างชาติ" และเจ้าหน้าที่เริ่มยึดบัตรประจำตัวประชาชนของชาวโรฮิงญา © Willy Legrendre/MSF

รัฐบาลพม่าเปิดยุทธการราชามังกร (นากามิน - Naga Min) มีการลงทะเบียนและตรวจสอบสถานะของพลเมืองและบุคคลที่ถูกตีตราว่าเป็น “ชาวต่างชาติ” ทหารทำการโจมตีและข่มขู่ชาวโรฮิงญา

สิ่งนี้ส่งผลให้ชาวโรฮิงญาราว 200,000 คนหลบหนีข้ามชายแดนไปยังบังกลาเทศ ซึ่งมีค่ายผู้ลี้ภัยตั้งอยู่ © Bangladesh/MSF

ชาวโรฮิงญาในบังคลาเทศบางส่วนถูกส่งตัวกลับประเทศพม่า ในบรรดาชาวโรฮิงญาที่ยังอาศัยอยู่ในบังกลาเทศ มีรายงานผู้เสียชีวิตราว 10,000 คน ซึ่งส่วนใหญ่คือเด็ก เรื่องจากการขาดแคลนอาหาร © John Vink/MAPS

รัฐสภาพม่าประกาศใช้กฎหมายฉบับใหม่ ซึ่งกำหนดความเป็นพลเมืองโดยพิจารณาจากชาติพันธุ์ โดยกฎหมายฉบับนี้ตัดสิทธิความเป็นพลเมืองของชาวโรฮิงญาและชุมชนชนกลุ่มน้อยอื่น © Bangladesh/MSF

หลังจากมีการลุกฮือของประชาชนที่ตามมาด้วยการปราบปราม รัฐบาลพม่าได้ประกาศเปลี่ยนชื่อประเทศเป็นเมียนมา (Myanmar)

รัฐบาลได้กำหนดให้ผู้คนในเมียนมาทำบัตรประจำตัวใบใหม่ เรียกว่าบัตรประจำตัวของบุคคลซึ่งอยู่ในระหว่างการพิจารณาเป็นพลเมือง (Citizenship Scrutiny Cards) ซึ่งชาวโรฮิงญาไม่เคยได้รับบัตรใบนี้

สภาฟื้นฟูกฎหมายและระเบียบแห่งรัฐได้เพิ่มปฏิบัติการทางการทหารในทางตอนเหนือของรัฐยะไข่ มีรายงานว่าชาวโรฮิงญาตกอยู่ภายใต้การบังคับใช้แรงงาน การบังคับย้ายถิ่นฐาน การข่มขืน การประหารชีวิต และการทรมาน ส่งผลใหเชาวโรฮิงญาหลายพันคนหลบหนีไปบังกลาเทศ © Willy Legrendre

กองทัพเมียนมาเปิดปฏิบัติการปิ ทายา (Pyi Thaya) หรือ “ปฏิบัติการทำความสะอาดเพื่อประเทศที่สวยงาม” ซึ่งในระหว่างนั้นทหารได้ก่อความรุนแรงเป็นวงกว้าง นำไปสู่สถานการณ์ที่ชาวโรฮิงญาราว 250,000 คน หลบหนีไปบังกลาเทศ

องค์การแพทย์ไร้พรมแดนให้บริการทางการแพทย์ในค่ายผู้ลี้ภัย 9 แห่งจาก 20 แห่งที่จัดตั้งขึ้นสำหรับชาวโรฮิงญาทางตะวันตกเฉียงใต้ของบังกลาเทศ โดยปริมาณอาหาร น้ำอุปโภคบริโภค และระบบสุขอนามัยในค่ายไม่เพียงพอ © John Vink/MAPS

รัฐบาลบังกลาเทศและเมียนมาลงนามในข้อตกลงเพื่อส่งผู้ลี้ภัยกลับประเทศ และค่ายผู้ลี้ภัยจะปิดรับผู้มาใหม่ในฤดูใบไม้ผลิ ในฤดูใบไม้ร่วงปีเดียวกันการบังคับให้ส่งตัวกลับประเทศเมียนมาเริ่มต้นขึ้น ท่ามกลางเสียงประท้วงจากประชาคมโลก รัฐบาลเมียนมาได้จัดตั้งกองกำลังรักษาความมั่นคงบริเวณชายแดนพิเศษที่เรียกว่า นาซากา (NaSaKa) เพื่อคุกคามข่มขู่และประหัตประหารชาวโรฮิงญา ในช่วงหลายปีต่อมา ชาวโรฮิงญาประมาณ 150,000 คนถูกส่งกลับไปยังเมียนมา และผู้ลี้ภัยรายใหม่ที่พยายามเดินทางถูกปฏิเสธไม่ให้เข้าบังกลาเทศ © MSF

รัฐบาลเมียนมาปฏิเสธออกสูติบัตรให้กับทารกชาวโรฮิงญา © Liba Taylor

บัตรลงทะเบียนชั่วคราว หรือ "บัตรขาว" เป็นเอกสารทางการที่รัฐบาลออกให้กับชาวโรฮิงญา ซึ่งไ่ม่ใช่บัตรที่รับรองสิทธิในฐานะพลเมืองของรัฐเมียนมา © A. Hollmann

ค่ายผู้ลี้ภัย 20 แห่งในประเทศบังกลาเทศช่วงปี 1990 เหลือเพียง 2 แห่งในปัจจุบัน สภาพแวดล้อมและการอยู่อาศัยเป็นไปอย่างยากลำบาก การวิจัยพบว่าเด็กร้อยละ 58 และผู้ใหญ่ร้อยละ 53 ในค่ายมีปัญหาด้านทุพโภชนาการ © Johannes Abeling

ชาวโรฮิงญามากกว่าหนึ่งหมื่นรายหนีออกจากประเทศเมียนทางทะเล เนื่องจากการต่อสู้อย่างรุนแรงระหว่างชุมชนพุทธและมุสลิมในรัฐยะไข่ © Giulio Di Sturco

องค์การแพทย์ไร้พรมแดนได้ปฏิบัติการด้านการแพทย์ในค่ายกูตูปาลอง (Kutupalong) ประเทศบังกลาเทศ มีผู้แสวงหาที่ลี้ภัยเพียงหยิบมือเท่านั้นที่ได้รับการรับรองสถานะผู้ลี้ภัย (refugee) ในบังกลาเทศ ในส่วนของผู้แสวงหาที่ลี้ภัยที่ไม่ได้รับรองสถานะต้องเผชิญกับความยากลำบาก ทั้งในส่วนของการคุกคามและการบังคับส่งตัวกลับประเทศ © Juan Carlos Tomasi

บัตรขาวเป็นเอกสารเพื่อบ่งชี้สถานะฉบับเดียวที่ชาวโรฮิงญามีอยู่ ถูกยกเลิกโดยรัฐบาลเมียนมา ในทางกลับกัน ชาวโรฮิงญาได้รับบัตรพิสูจน์สัญชาติ (national verification card) ซึ่งในทางกฎหมายใช้สำหรับชาวต่างชาติที่ไม่ใช่ชนพื้นเมืองเดิมในเมียนมา นับว่าชาวโรฮิงญาคือผู้อพยพจากบังกลาเทศ และชาวโรฮิงญาเกือบทั้งหมดถูกปฏิเสธการออกบัตรประจำตัวฉบับใหม่ © Alva Simpson White

วันที่ 9 ตุลาคม การโจมตีของกลุ่มติดอาวุธโรฮิงญากับตำรวจชายแดนในรัฐยะไข่ของเมียนมา ส่งผลกระทบต่อชุมชนโรฮิงญา ส่งผลให้ผู้ลี้ภัยและผู้ป่วยระลอกใหม่ข้ามชายแดนหลั่งไหลเข้ามายังคลินิกขององค์การแพทย์ไร้พรมแดนในค่ายชั่วคราวกูตูปาลอง ซึ่งให้บริการทางการแพทย์ครบวงจร เพื่อดูแลผู้ลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาและชุมชนท้องถิ่นในบังคลาเทศ © Alva Simpson White

หลังจากกลุ่มติดอาวุธชาวโรฮิงญาโจมตีสถานีตำรวจและกองทัพหลายแห่งในเมียนมาในวันที่ 25 สิงหาคม กองกำลังความมั่นคงของรัฐได้เริ่มใช้ความรุนแรงโดยมุ่งเป้าไปที่ชุมชนชาวโรฮิงญา ชาวโรฮิงญามากกว่า 700,000 คนถูกขับออกจากเมียนมาภายในไม่กี่สัปดาห์ การกระจัดกระจายของสาแหรกมวลชนเริ่มต้นขึ้นอีกครั้งในระดับตัวเลขที่ไม่เคยเกิดขึ้นมาก่อน องค์การแพทย์ไร้พรมแดนบันทึกการเสียชีวิตของชาวโรฮิงญามากกว่า 6,700 ราย ในช่วงเวลานี้

ปฏิบัติการทางการแพทย์ในบังกลาเทศ รวมถึงที่ดำเนินการโดยองค์การฯ เกิดขึ้นอย่างรวดเร็ว ในเดือนกันยายนองค์การฯ เรียกร้องให้เพิ่มความช่วยเหลือด้านมนุษยธรรมกับชาวโรฮิงญาในบังกลาเทศโดยทันที เพื่อหลีกเลี่ยงวิกฤติด้านสาธารณสุข องค์การฯ ยังเรียกร้องให้รัฐบาลเมียนมาอนุญาตให้องค์กรด้านมนุษยธรรมเข้าถึงรัฐยะไข่ทางตอนเหนือได้โดยอิสระ © Madeleine Kingston/MSF

ตั้งแต่เดือนธันวาคม รัฐบาลบังกลาเทศเริ่มย้ายผู้ลี้ภัยบางส่วนไปยังเกาะบาซันชาร์ (Bhasan Char) ซึ่งเป็นเกาะในอ่าวเบงกอลที่ยังไม่มีคนอาศัยอยู่จนถึงขณะนี้ ส่วนหนึ่งเนื่องมาจากความห่างไกลของพื้นที่และสภาพแวดล้อมที่แปรปรวน © Hasnat Sohan/MSF

ทางการบังกลาเทศกำหนดมาตรการล็อกดาวน์ที่เข้มงวดในช่วงการแพร่ระบาดของโควิด-19 ซึ่งจำกัดเสรีภาพในการเดินทางและโอกาสในการทำงานของชาวโรฮิงญามากขึ้น ท่ามกลางสถานการณ์ที่สิ้นหวังมากขึ้น ขณะที่กลุ่มติดอาวุธมีความเข้มแข็งมากขึ้นจากปฏิบัติการณ์ที่ใช้ความรุนแรงและการข่มขู่ โดยสภาพความเป็นอยู่ของชาวโรฮิงญายังคงย่ำแย่ลง เดือนมีนาคม เกิดเหตุเพลิงไหม้พื้นที่บาลูกคาลี ที่ทำให้มีผู้เสียชีวิต 11 ราย และทำลายคลินิกขององค์การฯ จากนั้นเดือนกรกฎาคมค่ายก็ประสบกับฝนตกหนักและน้ำท่วม

หลายชีวิตเลือกเสี่ยงชีวิตและอนาคตของตนเอง บางคนใช้เส้นทางอันตรายอย่างการอาศัยบนเรือค้ามนุษย์เพื่อข้ามอ่าวเบงกอลไปร่วมกับชาวโรฮิงญามากกว่า 100,000 คนที่อาศัยอยู่ในมาเลเซีย เรือเหล่านี้มักถูกทางการมาเลเซียจับไว้ แต่เมื่อพวกเขาถูกส่งตัวกลับมายังบังกลาเทศ ก็ถูกทางการบังกลาเทศขัดขวางและใช้ชีวิตอยู่กลางทะเลเป็นเวลาหลายสัปดาห์หรือบางครั้งก็เป็นเดือน

สภาพที่ยากลำบากในค่ายและอนาคตที่สิ้นหวังทำให้เกิดวิกฤตสุขภาพจิตในหมู่ชาวโรฮิงญาที่อาศัยอยู่ที่นี่ © Pau Miranda

5 ปีหลังจากการใช้ความรุนแรงแบบกำหนดเป้าหมายครั้งใหญ่ที่สุดที่เคยเกิดขึ้นต่อชาวโรฮิงญาในเมียนมา ผู้คนเกือบหนึ่งล้านคนอาศัยอยู่ในที่พักพิงที่ทำจากไม้ไผ่และพลาสติกแบบเดียวกันในคอกซ์ บาซาร์ โดยต้องอาศัยความช่วยเหลือขององค์การที่เกี่ยวข้อง และไม่มีวิธีแก้ปัญหาใดที่ดีไปกว่านี้อีกแล้ว © Saikat Mojumder/MSF

รายงานระดับภูมิภาคเกี่ยวกับสถานการณ์ชาวโรฮิงญา ประจำปี 2566 ในประเทศเมียนมา บังกลาเทศ และมาเลเซีย

รายงานฉบับนี้รวบรวมกิจกรรมการทำงานด้านมนุษยธรรมสำหรับชาวโรฮิงญาในภูมิภาค

- ชาวโรฮิงญาคือใคร

ชาวโรฮิงญาเป็นกลุ่มคนที่มาจากรัฐยะไข่ ประเทศเมียนมา ซึ่งมีพรมแดนติดกับบังกลาเทศทางตอนเหนือ พวกเขาส่วนใหญ่เป็นชาวมุสลิมซึ่งอาศัยอยู่ในประเทศที่นับถือศาสนาพุทธเป็นส่วนใหญ่มานานหลายศตวรรษ ทางการเมียนมาได้แย้งและประกาศว่าพวกเขาเป็นผู้อพยพอย่างผิดกฎหมายจากบังกลาเทศ

ก่อนการปราบปรามของทหารในเดือนสิงหาคม 2560 ชาวโรฮิงญาประมาณ 1.1 ล้านคนอาศัยอยู่ในประเทศเมียนมา

อันวาร์ อาราฟัต อายุ 15 ปี อาศัยอยู่ในค่ายผู้ลี้ภัยจัมโตลี กล่าวกับคนหนุ่มสาวทั่วโลกว่า “ฉันอยากจะพูดกับคนหนุ่มสาวในช่วงวัยเดียวกับฉันทั่วโลก โปรดใช้ชีวิตและใช้โอกาสที่คุณมีให้มากที่สุด ตัวฉันเองและเพื่อนผู้ลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาไม่มีโอกาสเช่นนั้น” บังคลาเทศ 2022 @Saikat Mojumder/MSF

การใช้ความรุนแรงแบบกำหนดเป้าหมาย

ชาวโรฮิงญาหลายแสนคนหลบหนีหลังจากที่รัฐบาลเมียนมาเพิ่มระดับความรุนแรงของปฏิบัติการทางทหาร เพื่อตอบโต้การโจมตีที่เกิดจากกองทัพกอบกู้โรฮิงญาแห่งอาระกันในปี 2560

ชาวโรฮิงญาเดินทางไปยังคอกซ์ บาซาร์ด้วยการเดินเท้า บนเรือ และบางครั้งก็โดยการลุยผ่านแม่น้ำที่แยกชายแดนบังกลาเทศ-เมียนมา

สิ่งนี้ทำให้ชาวโรฮิงญาได้รับการเสนอชื่อโดยองค์การสหประชาชาติในปี 2556 ให้เป็นชนกลุ่มน้อยที่ถูกข่มเหงมากที่สุดในโลก

จากการสำรวจขององค์การแพทย์ไร้พรมแดน ระหว่างวันที่ 25 สิงหาคม ถึง 24 กันยายน 2560 ชาวโรฮิงญาเสียชีวิตอย่างน้อย 6,700 คน โดยการประมาณการผู้คนเสียชีวิตจากการถูกสังหารอย่างน้อย 6,500 ราย รวมถึงเด็กอายุต่ำกว่า 5 ขวบ จำนวน 730 ราย สิ่งเหล่านี้ยืนยันรายงานขององค์กรข่าวระหว่างประเทศเกี่ยวกับความรุนแรงแบบกำหนดเป้าหมาย ซึ่งรัฐบาลเมียนมายังคงปฏิเสธ

- เหตุผลที่ชาวโรฮิงญากลายเป็นคนไร้รัฐ

ชาวโรฮิงญานับว่าเป็นชาวต่างชาติในเมียนมา ภายหลังการประกาศใช้กฎหมายพลเมืองในปี 2525 กฎหมายดังกล่าวไม่ยอมรับว่าพวกเขาเป็นหนึ่งใน "ชนพื้นเมือง" ของเมียนมา

ในขณะที่รัฐบาลเมียนมาเสนอการเป็นพลเมืองผ่าน "การฝึกเพื่อได้รับยืนยัน" ชาวโรฮิงญาไม่เต็มใจที่จะรับบัตรพิสูจน์สัญชาติ (NVC1) ซึ่งแม้จะถือครองไว้ พวกเขาก็ยังไม่สามารถเคลื่อนไหวได้อย่างอิสระภายในรัฐยะไข่หรือภายในประเทศ รวมถึงเข้าถึงบริการที่จำเป็นได้อย่างจำกัด เนื่องจากอุปสรรคของระบบราชการและแนวทางปฏิบัติในการเลือกปฏิบัติอื่นๆ

“เราไม่ได้ไร้สัญชาติ เรามาจากเมียนมา บรรพบุรุษของเรามาจากเมียนมา” – อาบู อาหมัด อายุ 52 ปี หนีไปบังกลาเทศเพื่อรับการรักษาอาการอัมพาตของลูกสาว บังกลาเทศ 2018 @Ikram N'gadi/MSF

- วิกฤตการณ์โรฮิงญาคืออะไร

25 สิงหาคม 2560 ผู้ลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาทั้งหมด 745,000 คน หลบหนีไปยังบังกลาเทศ ผู้ลี้ภัยจำนวนมากถูกรวมเข้ากับกลุ่มผู้ลี้ภัยที่เดินทางมาถึงก่อนหน้าภายในค่ายผู้ลี้ภัย ซึ่งต้องอาศัยอยู่ในสภาพที่ยากลำบากอยู่ก่อนแล้ว

ปัจจุบัน เขตคอกซ์ บาซาร์ เป็นที่ตั้งของผู้ลี้ภัยเกือบล้านชีวิต ทำให้ที่นี่กลายเป็นค่ายผู้ลี้ภัยที่ใหญ่ที่สุดในโลก

ที่พักพิงชั่วคราวที่ชาวโรฮิงญาอาศัยอยู่ อยู่ใต้สภาพอากาศที่รุนแรงและอุบัติเหตุไฟไหม้มาตั้งแต่ปี 2560 - บังคลาเทศ 2565 @Saikat Mojumder/MSF

ชาวโรฮิงญายังเสี่ยงชีวิตบนเรือข้ามทะเลอันดามันเพื่อหลบหนีไปยังประเทศอื่นๆ เช่น มาเลเซีย ไทย อินโดนีเซีย กัมพูชา และลาว

การพลัดถิ่นของผู้คนจำนวนมากในช่วงเวลาระยะสั้นครั้งนี้นับว่าเป็นการพลัดถิ่นที่ใหญ่ที่สุดในโลกในประวัติศาสตร์สมัยใหม่

- สถานการณ์ปัจจุบันของชาวโรฮิงญา

บังกลาเทศ

“การใช้ชีวิตในค่ายเป็นเรื่องยากลำบาก พื้นที่เล็กคับแคบ และไม่มีพื้นที่ให้เด็กได้เดินเล่น” – อาบู ซิดดิก ผู้อาศัยอยู่ในคอกซ์ บาซาร์ ประเทศบังกลาเทศ

นับตั้งแต่ปี 2560 เป็นเวลา 5 ปีแล้วที่ชาวโรฮิงญามากกว่า 770,000 คนหลั่งไหลเข้าสู่คอกซ์บาซาร์ พวกเขาเข้าไปอาศัยร่วมกับกับชาวโรฮิงญามากกว่า 250,000 คนที่ใช้ชีวิตอยู่ก่อนหน้า ปัจจุบัน ผู้คนเกือบ 1 ล้านคนอาศัยอยู่ในพื้นที่ราว 25 กิโลเมตรทางใต้ของเมืองคอกซ์ บาซาร์

รัฐบาลบังกลาเทศยินดีต้อนรับผู้ลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาที่หลบหนีความรุนแรงในเมียนมา และรับภาระส่วนใหญ่ในการจัดหาที่พักพิงและความช่วยเหลือด้านอาหารในช่วงเริ่มต้นของการหลั่งไหลเข้ามาในปี 2560 ในความร่วมมือกับรัฐบาลบังกลาเทศและผู้มีส่วนร่วมอื่นๆ ที่เกี่ยวข้อง จับมือเพื่อช่วยเหลือชาวโรฮิงญาในค่ายผู้ลี้ภัยในเขตคอกซ์ บาซาร์ องค์กรพัฒนาเอกชนหลายแห่งทำงานในค่ายเพื่อสนับสนุนความต้องการขั้นพื้นฐานบางส่วน รวมถึงการจัดเตรียมวัตถุดิบในการทำอาหาร (ส่วนใหญ่เป็นข้าวและน้ำมัน) แก๊สหุงต้ม บริการน้ำอุปโภคบริโภค และสุขาภิบาล การศึกษาขั้นพื้นฐาน (จนถึงโรงเรียนประถมศึกษาเท่านั้น) และบริการดูแลสุขภาพเบื้องต้น อย่างไรก็ตาม บริการเหล่านี้แทบจะไม่ครอบคลุมความต้องการของผู้ลี้ภัยในค่ายเกือบ 1 ล้านคน

ทางการบังคลาเทศและชุมชนเจ้าบ้านยังรู้สึกไม่สบายใจมากขึ้นกับสิ่งที่พวกเขามองว่าการทำงานในระดับนานาชาติกำลังละเลยเพื่อค้นหาวิธีแก้ไขวิกฤตินี้ เจ้าหน้าที่ยืนยันว่าการส่งตัวกลับประเทศควรเกิดขึ้นโดยเร็วที่สุด และการพังพิงในบังคลาเทศจะต้องคงอยู่เพียงชั่วคราว สิ่งนี้สะท้อนผ่านลักษณะของที่พักพิงผู้ลี้ภัยภายในค่าย เช่นเดียวกับสิ่งอำนวยความสะดวกขององค์กรพัฒนาเอกชนทั้งหมดที่ปฏิบัติการอยู่ที่นั่น สิ่งปลูกสร้างทั้งหมดภายในค่ายจำเป็นต้องใช้เฉพาะวัสดุโครงสร้างที่ไม่ถาวรเท่านั้น (เช่น ไม้ไผ่และกระดานไม้)

“ฉันแก่แล้วและกำลังจะตายในไม่ช้า ฉันสงสัยว่าฉันจะได้เห็นบ้านเกิดของฉันก่อนที่ฉันจะตายหรือไม่ ความปรารถนาของฉันคืออยากหยุดลมหายใจสุดท้ายของฉันในเมียนมา” โมฮาเหม็ด ฮุสเซน ชาวโรฮิงญาวัย 65 ปี แบ่งปันความปรารถนาของเขากับองค์การฯ - บังกลาเทศ 2022 @Saikat Mojumder/MSF

ที่แย่กว่านั้นคือ วิกฤตการณ์ทั่วโลกแบ่งความสนใจด้านมนุษยธรรมต่อชาวโรฮิงญา ตามประกาศของ UNOCHA เงินทุนสำหรับแผนเผชิญเหตุร่วมชาวโรฮิงยา (JRP) ลดลงจาก 629 ล้านดอลลาร์ในปี 2563 เหลือ 602 ล้านดอลลาร์ในปี 2564 ณ เดือนสิงหาคม 2565 เงินทุนอยู่ที่เพียง 266 ล้านดอลลาร์

เนื่องจากสภาพส่วนใหญ่ในค่ายย่ำแย่ ผู้คนที่พยายามหลบหนีส่วนใหญ่มักจะจ่ายเงินให้ผู้ลักลอบขนคนเข้าเมืองเพื่อพาพวกเขาไปยังมาเลเซีย อินโดนีเซียและไทยด้วย

ตั้งแต่เดือนธันวาคม 2563 เพื่อสร้างมาตรการที่ชัดเจนในการลดความแออัดในค่ายผู้ลี้ภัย ทางการบังกลาเทศเริ่มย้ายชาวโรฮิงญาไปยังเกาะบาซันชาร์ ซึ่งเสี่ยงต่อการเกิดน้ำท่วมขนาด 40 ตารางกิโลเมตร จนถึงขณะนี้ (เดือนกรกฎาคม 2022) มีผู้ย้ายที่อยู่แล้วมากกว่า 27,000 คน

มาเลเซีย

ผู้ลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาเดินทางไปยังมาเลเซียมานานกว่า 30 ปี โดยต้องเดินทางข้ามทะเลอันดามันที่เต็มไปด้วยอันตรายเพื่อค้นหาที่หลบภัยและความหวังสำหรับอนาคต อย่างไรก็ตาม ในมาเลเซีย ชีวิตของผู้ลี้ภัยยังคงเป็นการต่อสู้เพื่อศักดิ์ศรีและการยอมรับ มาเลเซียไม่ได้ลงนามในอนุสัญญาผู้ลี้ภัยแห่งสหประชาชาติปี 1951 และพิธีสารที่เกี่ยวข้อง นำไปสู่สถาวะที่ประเทศไม่ยอมรับหรือคุ้มครองผู้ลี้ภัยและผู้ขอลี้ภัยในกฎหมายภายในประเทศ ดังนั้น ผู้ลี้ภัยและผู้ขอลี้ภัยในมาเลเซียจึงถูกดำเนินคดีอาญา (เนื่องจากนับว่าเป็นการเข้าเมืองผิดกฎหมาย) และเข้าถึงบริการสาธารณะได้อย่างจำกัด รวมถึงการดูแลสุขภาพ

บัตรที่ออกโดยข้าหลวงใหญ่ผู้ลี้ภัยแห่งสหประชาชาติ (UNHCR) ให้ความคุ้มครองแก่ผู้ลี้ภัยและผู้ขอลี้ภัยที่ลงทะเบียนแล้ว แต่พวกเขายังคงขาดสถานะทางกฎหมาย ซึ่งหมายความว่าพวกเขามีความเสี่ยงที่จะถูกจับกุมและคุมขังอย่างต่อเนื่อง นอกเหนือจากการเผชิญกับอุปสรรคในการเข้าถึง การดูแลสุขภาพ การศึกษา และการจ้างงานทางกฎหมาย

ผู้ลี้ภัยจำนวนมากและชาวโรฮิงญา ไม่ว่าจะเป็นผู้ใหญ่หรือเด็ก ถูกควบคุมตัวในศูนย์กักกันคนเข้าเมืองทั่วประเทศ UNHCR ถูกปฏิเสธไม่ให้เข้าถึงศูนย์เหล่านี้ตั้งแต่เดือนสิงหาคม 2562 ส่งผลให้ UNHCR ไม่สามารถดำเนินการพิจารณาสถานะผู้ลี้ภัยได้ และไม่สามารถขอปล่อยตัวผู้ขอลี้ภัยและผู้ลี้ภัยที่ถูกควบคุมตัวได้

องค์การฯ สังเกตเห็นความรู้สึกต่อต้านชาวโรฮิงญาเพิ่มขึ้นนับตั้งแต่เริ่มมีการระบาดใหญ่ของโควิด-19 ในปี 2563 ซึ่งใกล้เคียงกับการเปลี่ยนแปลงรัฐบาล หลังจากมีข่าวการเดินทางมาถึงทางเรือใหม่หลายครั้งเมื่อต้นปี รัฐบาลได้แสดงจุดยืนที่รุนแรงต่อผู้ลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาโดยป้องกันไม่ให้เรือเข้าถึงชายฝั่ง กระชับพรมแดนทางบกและทางทะเลของประเทศ และเพิ่มการจู่โจมโดยเจ้าหน้าที่ตรวจคนเข้าเมืองทั่วประเทศ โดยกำหนดเป้าหมายไปยังพื้นที่ที่ผู้ลี้ภัยและผู้อพยพอาศัยและทำงาน

มีรายงานการมาถึงของเรือลำใหม่ 3 ลำในเดือนพฤษภาคม 2565 องค์การฯ ทราบว่าการมาถึงเหล่านี้ประกอบด้วยผู้ชายมากกว่าผู้หญิง ซึ่งถือว่าแตกต่างไปจากแนวโน้มในอดีต ซึ่งการเดินทางส่วนใหญ่ดำเนินการโดยผู้หญิงและเด็กผู้หญิง มีรายงานว่า ผู้ลี้ภัยและผู้ขอลี้ภัยชาวโรฮิงญาที่เพิ่งมาถึงถูกตั้งข้อหาในศาล และขณะนี้อยู่ในเรือนจำหรือถูกควบคุมตัวโดยคนเข้าเมือง องค์การฯ ได้พยายามเข้าถึงบุคคลเหล่านี้เพื่อให้ความช่วยเหลือทางการแพทย์และการสนับสนุนด้านสุขภาพจิต ทว่า ความพยายามขององค์การฯ ไม่ประสบความสำเร็จ

เมียนมา

ชาวโรฮิงญาราว 600,000 คนยังคงอยู่ในรัฐยะไข่ โดยราว 140,000 คนอาศัยอยู่ในเขตสำหรับผู้พลัดถิ่น รวมถึงค่ายพักต่างๆ ที่พวกเขามีเสรีภาพในการเคลื่อนย้ายที่จำกัด ผู้ที่อาศัยอยู่ในหมู่บ้านยังต้องการเอกสารทางราชการที่มีราคาแพงในการเดินทางและเข้าถึงบริการขั้นพื้นฐานได้อย่างจำกัด

ในบรรดาชาวโรฮิงญาที่อาศัยอยู่ในรัฐยะไข่ การทำรัฐประหารของทหารไม่ใช่เปลี่ยนแปลงครั้งสำคัญสำหรับพวกเขา เพราะมันย่ำแย่มากก่อนวันที่ 1 กุมภาพันธ์ และตอนนี้ก็ยังแย่อยู่ แม้จะอาศัยอยู่ในเมียนมามาหลายชั่วอายุคนก็ตาม ภายใต้กฎหมายความเป็นพลเมืองเมียนมาร์ปี 1982 ชาวโรฮิงญาไม่ได้รับการพิจารณาให้เป็นหนึ่งใน “135 เชื้อชาติของชนพื้นเมืองอย่างเป็นทางการ” และด้วยเหตุนี้จึงถูกแยกออกจากการเป็นพลเมืองโดยสมบูรณ์ ทำให้พวกเขาไร้สัญชาติ สิ่งนี้นำไปสู่การละเมิดสิทธิมนุษยชนมากมาย พวกเขาถูกปฏิเสธเสรีภาพในการเคลื่อนย้าย และต่อมาก็เข้าถึงการรักษาพยาบาล การศึกษา และการดำรงชีวิต

ค่ายผู้ลี้ภัยยังคงคับแคบและสกปรก ไม่มีวี่แววว่าผู้คนจะได้รับอนุญาตให้กลับไปยังหมู่บ้านที่พวกเขาถูกขับไล่ออกไป และความจริงสำหรับหลายคนก็คือ บ้านของพวกเขาหายไปแล้วตลอดกาลหรือถูกครอบครองโดยกลุ่มชาติพันธุ์อื่น

เงื่อนไขการใช้ชีวิตในเมียนมาไม่สอดคล้องกับความพยายายามให้ชาวโรฮิงญากลับจากบังกลาเทศอย่างปลอดภัยและสมัครใจ ครอบครัวถูกแบ่งแยกไม่เพียงแต่ในหมู่ผู้ที่หลบหนีไปยังบังกลาเทศเท่านั้น แต่ยังรวมถึงเมื่อชาวโรฮิงญาเริ่มต้นการเดินทางที่เต็มไปด้วยอันตรายไปยังประเทศต่างๆ โดยเฉพาะมาเลเซีย เพื่อค้นหาโอกาสที่ดีกว่า ภาวะเหล่านี้มีผลกระทบร้ายแรงต่อสุขภาพจิตของผู้ที่เหลืออยู่ในเมียนมา

ผลกระทบของการยึดอำนาจของทหารจากการระบาดใหญ่ทำให้เกิดความวุ่นวายทางเศรษฐกิจในประเทศ โดยค่าจ๊าตพุ่งตรงเมื่อเทียบกับดอลลาร์ ส่งผลให้ราคานำเข้าพุ่งสูงขึ้น เชื้อเพลิงและอาหารมีราคาสูงขึ้น โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในรัฐยะไข่ซึ่งต้องพึ่งพาการขนส่งสินค้าเข้ามาจากพื้นที่อื่นของประเทศ

ความตึงเครียดในรัฐยะไข่ระหว่างกองทัพอาระกันและกองทัพเมียนมาร์กำลังเพิ่มมากขึ้น แม้ว่าชาวโรฮิงญาจะไม่เกี่ยวข้องโดยตรงกับความขัดแย้งนี้ แต่ความไม่มั่นคงที่เพิ่มขึ้นอาจทำให้ชาวโรฮิงญาจมอยู่กับความรุนแรง และส่งผลกระทบต่อการทำงานขององค์การฯ และการเข้าถึงชุมชน

องค์การฯ เผชิญกับการกีดขวาง ณ จุดตรวจสอบ จุดตรวจของกองทัพเรือระหว่างทางไปคลินิกขององค์การฯ เมืองพัคตอใช้เวลาประมาณสองชั่วโมงโดยเฉลี่ย ทำให้เวลาเปิดทำการของคลินิกลดลงครึ่งหนึ่ง และการให้คำปรึกษาทางการแพทย์ลดลง 30% ในหนึ่งสัปดาห์ องค์การฯ ประมาณการว่าผู้ป่วยประมาณ 200 รายต่อสัปดาห์ที่ขาดโอกาสในการเข้ารับการรักษาพยาบาล