Breadcrumb

- Home

- Remember the Rohingya - What we do

What we do

Unyielding Commitment to the Rohingya

For decades, Doctors Without Borders has been at the forefront of addressing the Rohingya refugee crisis with unwavering dedication. Our mission commenced in Bangladesh in 1985, and over the years, we have significantly broadened our medical humanitarian efforts to encompass the Rohingya diaspora in neighboring countries, forming an integral part of our comprehensive strategy to tackle the crisis.

At present, our projects span across Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Malaysia, where we tirelessly deliver essential medical care to the Rohingya population in their most critical times of need.

Regional Rohingya Activity Report 2023 - Myanmar, Bangladesh and Malaysia

This report highlights our initiatives and actions in response to the humanitarian needs of the Rohingya community in the region.

Doctors Without Borders has significantly expanded its operations in Bangladesh since August 2017 to address the healthcare needs of over 1,000,000 Rohingya refugees in the camps, as well as the local host community. With a team of over 2,000 staff, Doctors Without Borders provides a wide range of services, including general healthcare, treatment for chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension, emergency services, women’s healthcare, mental health support, and care for survivors of gender-based violence. Doctors Without Borders also works to improve water and sanitation facilities within the camps.

Recently, Doctors Without Borders has been responding to an increase in violence-related injuries among Rohingya refugees crossing the border from Myanmar. In early August 2024, Doctors Without Borders treated 39 people for such injuries, including mortar shell and gunshot wounds, with women and children making up over 40 per cent of the patients. This surge in violence has raised concerns about the worsening humanitarian crisis in Myanmar and the impact on the Rohingya population, many of whom face life-threatening conditions and perilous journeys to seek safety in Bangladesh.

In addition to emergency care, Doctors Without Borders is addressing a significant public health issue in the camps: hepatitis C. A study conducted by Doctors Without Borders revealed that almost 20 per cent of the Rohingya refugees tested in Cox’s Bazar camps have an active hepatitis C infection. Doctors Without Borders has been the sole provider of hepatitis C care in these camps since October 2020, but the need for treatment far exceeds the available capacity. With over 8,000 patients treated so far, Doctors Without Borders’s facilities can only accommodate 150 to 200 new patients per month, leading to strict admission criteria and the need for a broader humanitarian response.

Doctors Without Borders is advocating for a large-scale prevention and ‘test and treat’ campaign to combat the hepatitis C epidemic in the camps.

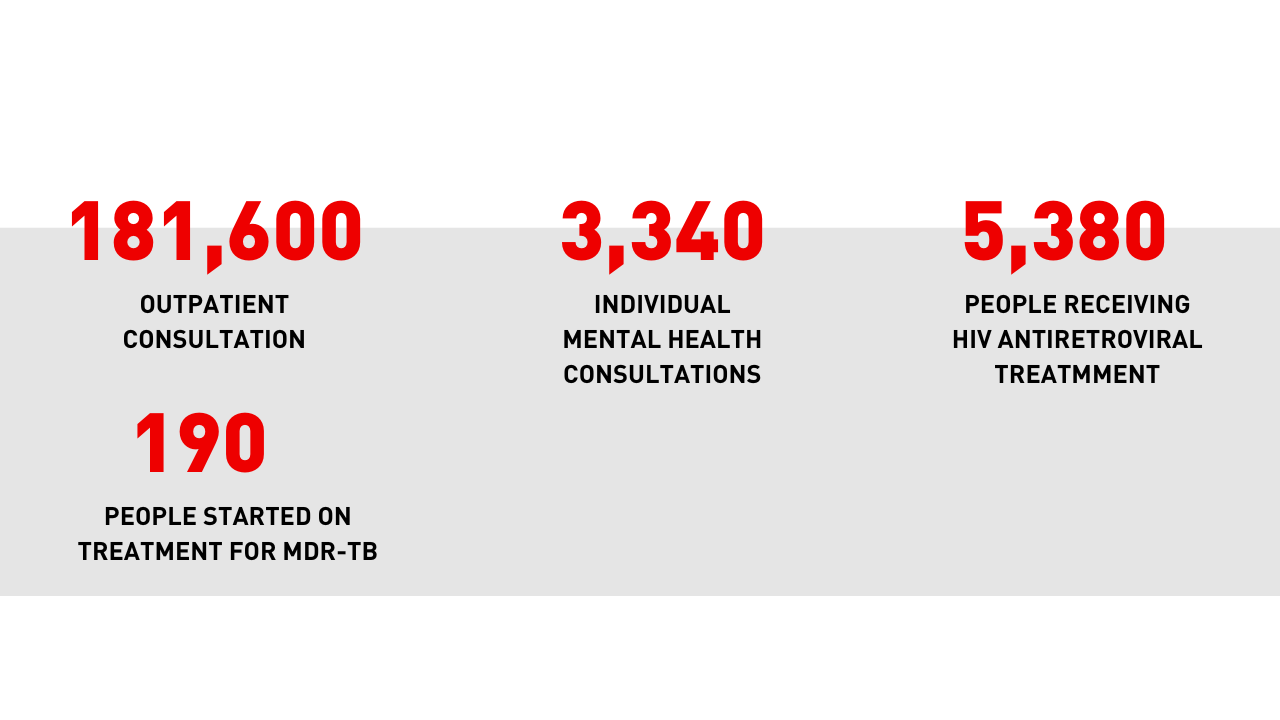

Highlights of our activities in Bangladesh

In 2023

Doctors Without Borders has been providing healthcare to refugees, asylum-seekers, and undocumented migrant communities in Malaysia since 2015. Initially part of a broader response to the refugee crisis, Doctors Without Borders established a programme in Penang to offer primary healthcare, mental health services, psychosocial support, and counseling to these vulnerable populations.

In 2018, Doctors Without Borders set up a fixed clinic in Butterworth, which currently serves around 900 to 1,000 patients each month. Additionally, weekly mobile clinics, run in partnership with the local NGO ACTS (A Call to Serve), extend services to refugees in more remote areas of Penang. Doctors Without Borders collaborates with local clinics and hospitals for referrals and provides medical support to several Immigration Detention Centres (IDCs) in cooperation with local NGOs.

Through advocacy and liaison efforts, Doctors Without Borders assists refugees and asylum-seekers needing protection, referring cases to UNHCR and working with Malaysian partners to identify service gaps. Doctors Without Borders's advocacy includes calls for the repeal of Health Circular 10/2001 and the safe disembarkation of refugees in distress at sea. Additionally, Doctors Without Borders collaborates with local partners and state institutions on long-term improvements to refugees' access to healthcare.

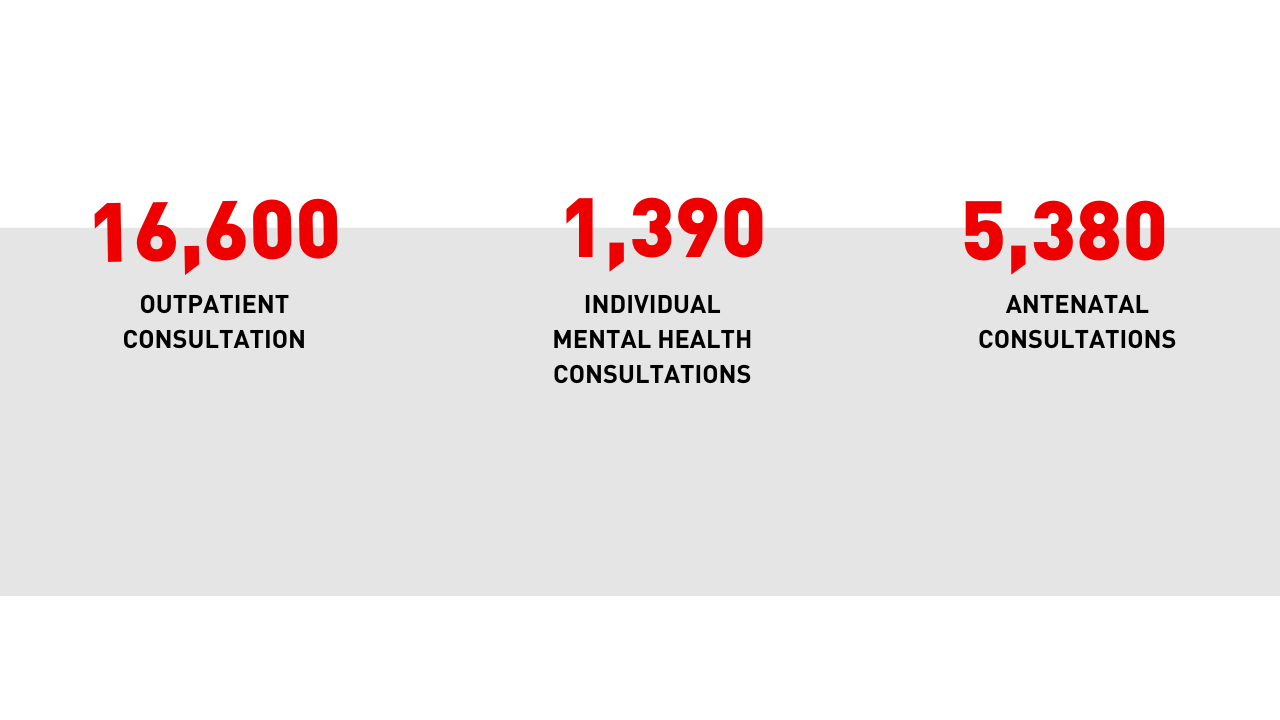

Highlights of our activities in Malaysia

In 2023

Since November 2023, Doctors Without Borders has faced significant challenges in providing healthcare in Myanmar due to the resumption of conflict between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army. For eight months, Doctors Without Borders was unable to operate mobile clinics in Rakhine State, including in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in Pauktaw Township, where Doctors Without Borders is often the sole healthcare provider. The ongoing conflict has made it nearly impossible for Doctors Without Borders teams to reach patients, and travel restrictions have prevented the transport of emergency patients to hospitals.

In June 2024, Doctors Without Borders briefly resumed its mobile clinic in Sittwe’s Aung Mingalar quarter, though with limited capacity due to severe supply constraints. However, many areas, including Pauktaw Township, remain inaccessible. Travel restrictions also prevent Doctors Without Borders from delivering medicines to the camps, exacerbating the already critical situation. Emergency referrals, once a lifeline for patients needing specialized care, are now blocked, leaving many without access to essential healthcare. The ongoing conflict has led to an alarming increase in maternal and neonatal deaths.

Public healthcare facilities in Rakhine State have also been severely impacted, with many closing due to safety concerns and shortages of staff, supplies, and fuel. Teleconsultations, a lifeline for some patients, are often hampered by poor phone signal, making it difficult for communities to access even remote medical support.

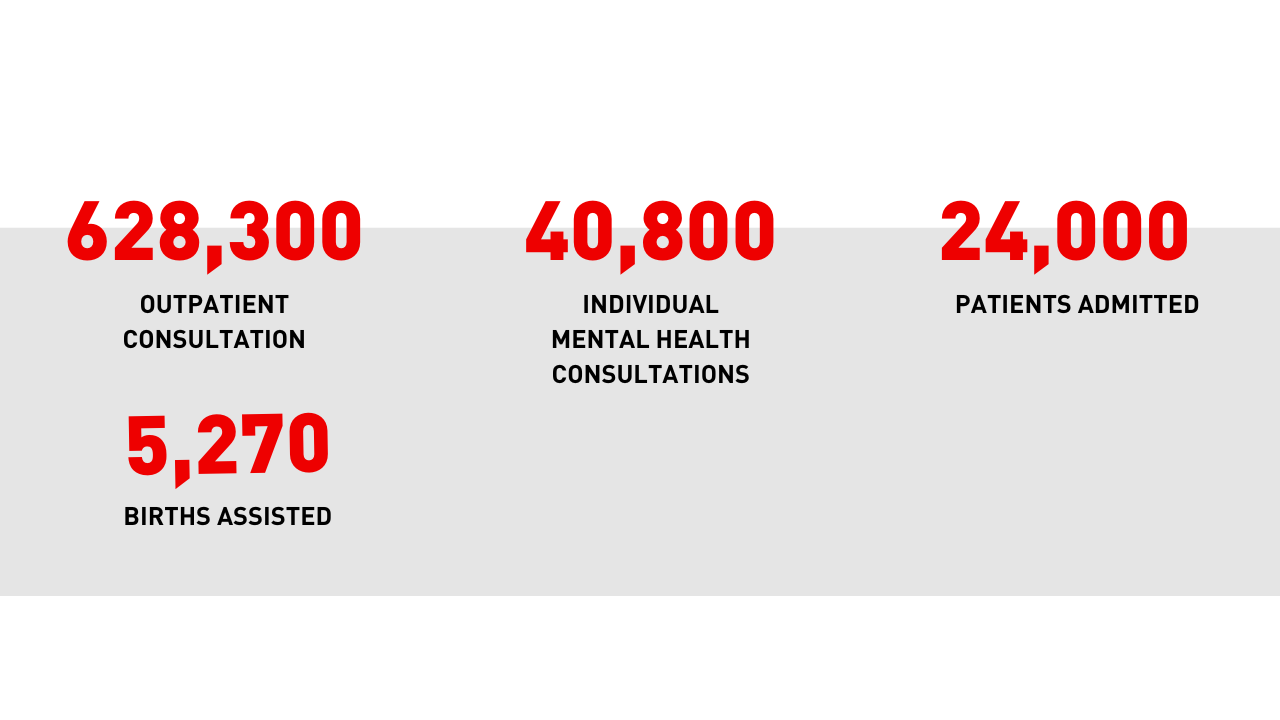

Highlights of our activities in Myanmar

In 2023