Bangladesh: Lack of hepatitis C care amid alarming prevalence rates in Rohingya refugee camps

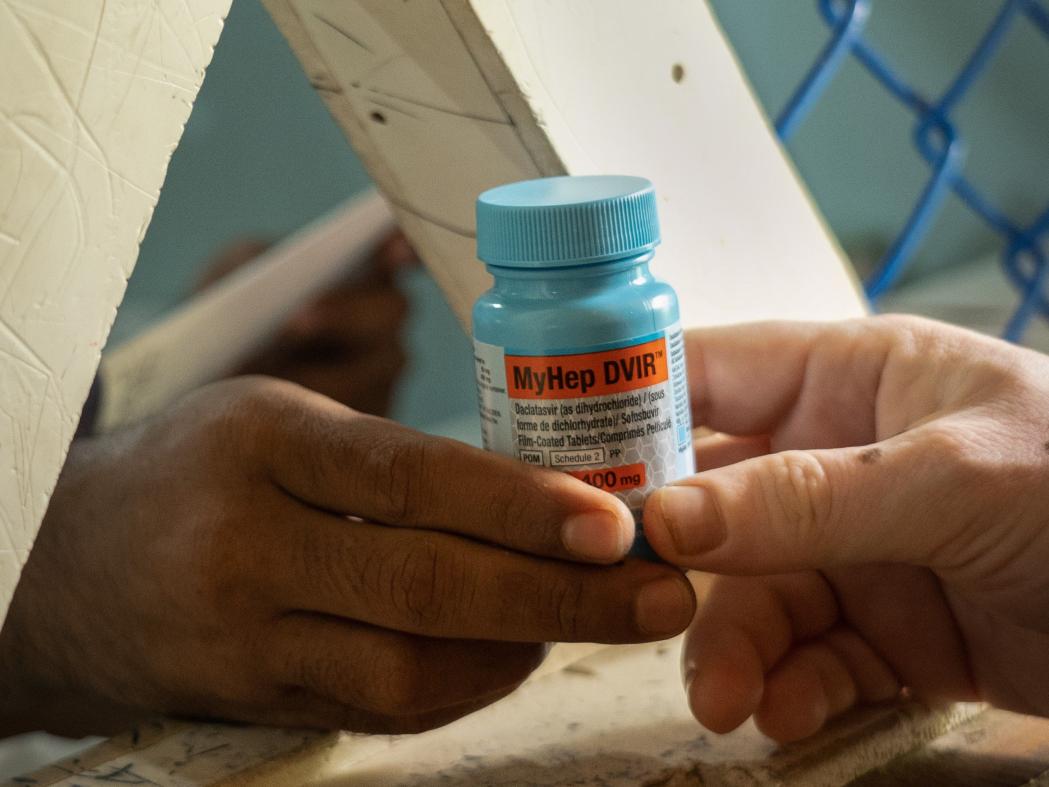

A patient is receiving medicines for Hep C from Doctors Without Borders’ Jamtoli facility at the Rohingya refugee camp in Ukhiya, Cox’s Bazar. Bangladesh, May 2024. © Abir Abdullah/MSF

- A study carried out by Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) indicates that almost 20 per cent of the Rohingya refugees tested in the Cox's Bazar camps in Bangladesh have an active hepatitis C infection.

- A blood-borne virus, hepatitis C is a disease that can remain dormant for a long time in those infected. If untreated, it can attack the liver and lead to serious or even fatal complications, usually cirrhosis or liver cancer, with an increased risk of developing several conditions including diabetes, depression and heavy fatigue.

- In the camps, people have very limited diagnostic and treatment options. Doctors Without Borders is calling for a joint humanitarian effort to combat the disease among this stateless population already deprived of basic rights and heavily dependent on aid for survival.

Faced with an influx of hepatitis C patients in the Cox’s Bazar camps over the last few years, Epicentre, Doctors Without Borders' epidemiology and research centre, carried out a survey of 680 households in seven camps between May and June 2023. The results show that almost a third of the adults in the camps have been exposed to hepatitis C infection at some point in their lives and that 20 per cent have an active hepatitis C infection.

“As one of the most persecuted ethnic minorities in the world, the Rohingya population is paying the price for decades of lack of access to healthcare and to safe medical practices in their country of origin. The use of healthcare equipment that has not been disinfected, such as syringes, which are widely used in alternative healthcare practices within the refugee community, could explain the potential ongoing transmission and the high prevalence of hepatitis C among the population living in the overcrowded camps", explains Sophie Baylac, Doctors Without Borders head of mission in Bangladesh.

Extrapolating the results of this study to all the camps would suggest that about one in five adults is currently living with a hepatitis C infection – totalling an estimated 86,000 individuals – and requiring treatment to be cured.

Our teams have to turn away hepatitis C patients every day, because the need for care exceeds the capacity of our organisation alone. There are barely any other available and affordable alternatives for these patients outside our clinics in the camps. This is a dead end for a stateless population deprived of the most basic rights, already facing dead ends in all areas of their daily lives.Sophie Baylac, Head of Mission

Access to diagnosis and treatment is inadequate in many low- and middle-income countries, making this disease a potential public health threat. Yet, direct-acting antiviral drugs can cure over 95 per cent of those infected.

In the overcrowded refugee camps of Cox's Bazar, access to diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus is almost non-existent. Doctors Without Borders has been the sole provider of hepatitis C care there for four years. Yet the need for treatment is extremely high.

Refugees are not legally allowed to work or leave the camps. For those we cannot treat, paying for expensive diagnostic tests and drugs or obtaining appropriate care outside the camps is out of their reach. “Most refugees simply cannot be cured and resort to alternative methods of care, which are not effective and not without risks to their health,” says Sophie Baylac.

Doctors Without Borders staff is collecting blood sample from a patient to run Hep C rapid diagnostic test (RDT) at the Hepatitis C consultation room of Hospital on the hill at Ukhiya, Cox’s Bazar. Bangladesh, May 2024. © Abir Abdullah/MSF

We welcome the announcement by the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Save The Children that 900 hepatitis C patients are to be treated in two health centres in the camps. This is an important step in the right direction. However, a large-scale prevention ‘test and treat’ campaign is needed to effectively limit the transmission of the virus and avoid severe liver complications and deaths. For this, the involvement and determination of those coordinating the humanitarian response in the Cox's Bazar camps will be required.Sophie Baylac, Head of Mission

“Every generation of refugees living in the camps is affected by hepatitis C. They risk severe liver complications – which are not treatable in camp settings – and may die from it despite the existence of a very effective, well tolerated and patient-friendly treatment (one tablet per day for three months) that can be inexpensive,” Sophie Baylac continues.

WHO guidelines and simplified models of care used by Doctors Without Borders in similar contexts have proved efficient to scale up hepatitis C treatment with very good outcomes in humanitarian and low-resource settings. Over the past two years, Doctors Without Borders has also supported the Bangladesh Ministry of Health in drafting national clinical guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis C.

Doctors Without Borders stands ready to continue working with national authorities, inter-governmental and non-governmental organisations to implement large-scale prevention and health promotion activities, as well as a mass ‘test and treat’ campaign in all Cox's Bazar camps in order to limit the virus transmission and treat as many patients as quickly as possible.

Doctors Without Borders work in Bangladesh:

Since October 2020, Doctors Without Borders has been offering free hepatitis C virus screening, diagnosis and treatment to the refugee population in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, at two of our health facilities in the camps (Jamtoli Clinic and Hospital on the Hill). From October 2020 to May 2024, over 12,000 individuals with suspected active hepatitis C infection have been tested by Doctors Without Borders with the GeneXpert diagnostic machine.

Over 8,000 patients with confirmed active infection have received treatment in Doctors Without Borders facilities. Due to the high number of HCV patients, soon after the start of the programme, our teams had to limit and establish admission criteria mainly based on patients being aged over 40, as our capacity to absorb the care needs of people with hepatitis C had quickly reached capacity. Doctors Without Borders' treatment programme has a maximum capacity of 150 to 200 new patients requiring treatment per month.

Through its ‘Time for $5’ Campaign, Doctors Without Borders has been putting pressure on the medical test maker Cepheid and its parent corporation Danaher to lower the price of the GeneXpert hepatitis C viral load test used to diagnose hepatitis C. The test is currently sold to low- and middle-income countries at US$15 each – this is more than three times what Doctors Without Borders-commissioned research has shown the tests could cost to produce and be sold for with a profit, which would be $5 each. Following campaign pressure, in September 2023, Danaher announced it would reduce the price of the standard tuberculosis test from $10 to $8 each. However, Danaher continues to charge at least double that price for tests for other diseases, including hepatitis C. Doctors Without Borders is asking Cepheid and Danaher to reduce the price of all tests to $5 so that more people can access this diagnostic test, which could lead to lifesaving treatment, and especially vulnerable people such as the refugees in Cox's Bazar camps in Bangladesh.