Breadcrumb

- Home

- Infectious But Not Invincible

- Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C: The Silent Killer

There are reports of the hepatitis virus existing since 400 BC. However, it was only first described in the middle of the 19th century. In the 1970s, the hepatitis A and B viruses were formally identified. Several years later, scientists observed that following blood transfusions, some patients became infected with a new a form of hepatitis. This new infection has been identified in April 1989 as hepatitis C virus or HCV.

Worldwide, an estimated 58 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in 2019, 72% of whom live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

How is Doctors Without Borders Responding to Hepatitis C?

Doctors Without Borders treats people with hepatitis C in several countries, and has dedicated HCV projects in Iran, Myanmar, Ukraine, Pakistan, India and Cambodia.

In 2019, Doctors Without Borders provided HCV treatment to some 10,000 people globally.

Cambodia

Doctors Without Borders is working with the Cambodian Ministry of Health to increase people’s access to care and has researched and introduced innovative ways of diagnosing and treating HCV in Cambodia. First, all patients now receive the same treatment regardless of the type and stage of their liver disease, which means they no longer need most of the pre-treatment analysis required by earlier treatments. Second, direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) are very safe, so additional tests and monitoring, which used to take place before and during treatment, are no longer necessary. In total, patients now need only five medical consultations instead of 16, which means it's easier and more affordable to adhere to or to complete the treatment. More than 13,000 patients have been treated under the new regimen since 2016.

In the 1990s to 2010s, hepatitis treatment lasted anywhere between six to 12 months. On top of that, it wasn’t well tolerated, with negative side effects, and the patient had to be monitored closely. Worse still, the treatment wasn’t very effective, as the virus was only eliminated in around 50% of cases.

Treatment has been simplified in the past five years. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), a not-for-profit research organisation developing new treatments for neglected patients which was partly founded by Doctors Without Borders, is working to deliver a treatment that is as effective as the best HCV drugs, at a fraction of the cost. A new generation of treatments called DAAs was introduced at the end of 2013. DNDi led several clinical trials of ravidasvir (RDV) and sofusbuvir (SOF) in Malaysia in 2016, co-sponsored by the Malaysian Ministry of Health, and in Thailand in 2017, in partnership with the government.

Initial results presented in 2018 showed that 12 weeks after treatment completion, 97% of those enrolled in the treatment were cured. This means HCV is not detectable in the blood three months after completing the treatment. The results indicate that the RDV/SOF combination is comparable to the very best HCV therapies available today. This also shows that such a regimen has potential to be the simple and affordable treatment that cures existing HCV strains.

In June, 2021, Malaysia approved the use of Ravida®, which is indicated in combination with other medicinal products for the treatment of HCV infection in adults. This is the outcome of years of collaboration between DNDi and the Malaysian government to reduce barriers in access and affordability of HCV drugs for patients in Malaysia.

In the past years, Doctors Without Borders —through Access Campaign and DNDi—is advocating to lower the price of the DAAs and make it more accessible to patients who need it most. In 2018, around 3 million patients—out of the 71 million people worldwide who are living with HCV—have been enrolled in DAA treatments.

DAAs represent a treatment breakthrough for people with HCV. However, access to DAAs is limited because pharmaceutical corporations charge unaffordable prices. In some places, these corporations have even blocked the entry of affordable generics with patents. This has led many countries to reserve treatment only for people with the most advanced stages of the disease.

Although the estimated manufacturing cost for a 12-week course of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir is less than US$100, the manufacturers Gilead and Bristol-Meyers Squibb priced them at a staggering US$147,000 per treatment when they launched them in the United States. The move drew widespread outrage, but exorbitant prices remain a deadly barrier to treatment in both high-income and developing countries.

Since the launch of the first DAAs, Doctors Without Borders worked to close the HCV treatment gap with strategies aimed at increasing access to affordable, quality-assured generic versions of the drugs. In a major milestone of 2017, Doctors Without Borders’ supply centres and Access Campaign team negotiated successfully with generics manufacturers to procure DAAs for just $120 per treatment in almost all Doctors Without Borders projects, allowing teams to start more people on treatment.

REAL PEOPLE, REAL STORIES

Police officer Din Savorn was in despair. This 50-year-old father of three living in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, learned that new medicines which could cure his hepatitis C existed but were unaffordable.

“I wanted to get treated, but I couldn’t afford it,” he says. “I would have had to sell my house. Then my children would have no shelter. So, I just waited.”

Din Savorn carries his son to daycare in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. April 2017. © Todd Brown

Din Savorn poses with his children at his apartment in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. April 2017. © Todd Brown

Din Savorn receives news that the hepatitis C treatment was a success, from Doctors Without Border's Doctor Hang Vithuneat, at the Doctors Without Borders' Hepatitis C clinic at Preah Kossamak Hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. April 2017. © Todd Brown

Then he saw on social media that Doctors Without Borders was offering free treatment locally. In early 2017, Din started treatment at a Doctors Without Borders clinic in Phnom Penh, the only facility in Cambodia providing HCV treatment free of charge. By May 2017, he got the news he had waited almost 20 years to hear: his treatment was a success. He was cured.

Breakthrough medicines can cure HCV in just 12 weeks and can turn people’s lives around. But millions of people are still missing out and cannot access these lifesaving treatments.

- What is hepatitis C?

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, and may be caused by any of the five viruses – hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Among these, hepatitis C virus or HCV is considered one of the deadliest, and also the most difficult to treat. HCV has eight genotypes or strains and 86 subtypes, among which are 19 novel subtypes recently identified. These many strains and subtypes, and its nature as a fast-mutating RNA virus, make HCV very difficult to treat.

HCV is considered a “silent killer” because people are often unaware of their infection, going untreated for years. They show no symptoms of the disease and therefore do not seek treatment.

- Is hepatitis C similar to HIV?

HCV and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are both RNA viruses. They enter and replicate their genetic material in the cytoplasm or the fluid portion of the cell. Although HCV is a flavivirus and HIV is a retrovirus, both viruses mutate rapidly, making it harder to create a vaccine against them.

It is possible for a patient to have both HCV and HIV. This is called a coinfection. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that HCV affects 2% to 15% of people living with HIV worldwide, and up to 90% of those are people who inject drugs (PWID). The global burden of HIV-HCV coinfection is 2.3 million people, of whom 1.3 million people are PWID. These co-infections are greatest in the African and Southeast Asian regions.

- How is hepatitis C transmitted?

HCV is a blood-borne virus, spreading through the body via the bloodstream following blood transfusions or unsafe drug injection. It may also be transmitted through unsafe healthcare settings, transfusion of unscreened blood and blood products, and sexual practices that lead to exposure to blood.

Scientists think it is also possible for HCV to be transmitted from mother to foetus during pregnancy, though according to WHO, these modes of transmission are less common.

- Can hepatitis C kill you?

Hepatitis C is one of deadliest forms of hepatitis. The WHO estimates that nearly 300,000 people died from HCV in 2019, mostly from resulting complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. For every 100 people infected with HCV, about five to 25 will develop cirrhosis in the next 10 to 20 years.

Patients with HCV are more likely to develop cirrhosis if they are male, aged over 50, consume alcohol, or have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or hepatitis B or HIV coinfection.

However, hepatitis C is a curable disease.

- What does hepatitis C do to the body?

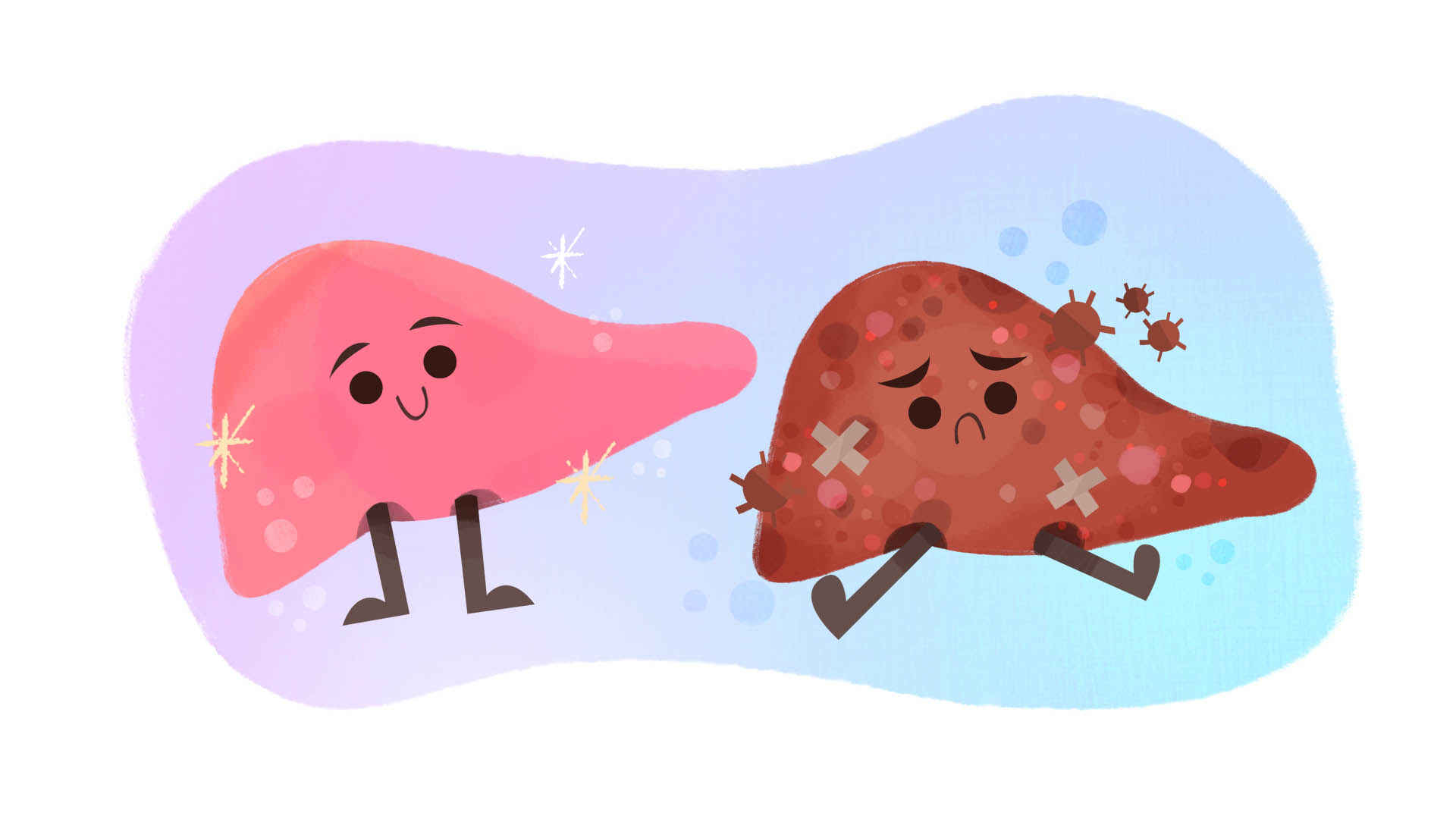

Once in the body, HCV attacks the liver. It gets into the lobules, which are microscopic units that enable the liver to function. Like all viruses, HCV has to penetrate a cell to survive and multiply.

Alerted to the intrusion, the body sends in immune cells, which are its first line of defence. But in eliminating the virus, they also destroy the liver cells that harbour them.

According to WHO, around 30% of infected persons spontaneously clear the virus within six months of infection without any treatment.

But more often, the immune cells aren’t up to the task. The infection can become chronic after six months, as the virus continues to multiply and infect more lobules that are then destroyed by the immune cells. This can lead to a scarring process called liver fibrosis. The liver shrinks and hardens, and its blood vessels flatten, forcing the blood to bypass it.

More advanced fibrosis may eventually lead to cirrhosis, which is more severe and can cause irreversible damage. Cirrhosis is a risk factor for liver cancer, which can develop at any stage of the liver disease.

- Who is most prone to hepatitis C?

Most prone to being infected with HCV are people who use injection drugs (PWID); people who are in prisons and other closed settings with poor hygiene; and people who receive infected blood products or invasive procedures with inadequate infection control practices.

Other people who are at increased risk of infection are children born to mothers infected with HCV; people with sexual partners who have HCV or HIV infection; and people with tattoos or piercings.

Healthcare workers and public safety personnel may also be exposed to HCV if they experience injury from a sharp implement, such as a needle or a scalpel used on an HCV positive patient.

- When should you meet the doctor or seek treatment?

If you are at high risk of contracting HCV, you should consider getting tested. Most HCV infection remains asymptomatic until decades after infection. See a doctor if you experience a combination of these symptoms: fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, yellowing of the skin and eyes, dark urine, nausea, and vomiting.

- Can hepatitis C be eradicated?

Hepatitis C is a curable disease, but millions are not able to access treatment due to prohibitive costs. To successfully eradicate this disease, there must be significant changes in diagnosis and treatment.

Existing diagnostic tests, serological or nucleic acid tests, are too complex and/or too expensive for countries with limited budgets, weak health systems, or both. Simple, more affordable tests are needed.

Fortunately, WHO said that global leaders have committed to eliminating HCV as a major public health threat by aiming to treat 80% of people with HCV globally by 2030.

- How can you prevent or treat hepatitis C?

For blood transfusion and other invasive surgeries, go to healthcare facilities that practice proper infection prevention and control measures, as well as safe handling and disposal of syringes and medical waste.

To prevent exposure to blood during sex, use condoms correctly and consistently.

Currently, Doctors Without Borders is pushing for direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) that are safe and effective in the treatment of HCV infection. Estimates indicate that only 9.4 million people worldwide had been treated with HCV treatment regimens by 2019, leaving 48.6 million people waiting for access to safer, more tolerable and more effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) to treat their HCV infection.

- Can you still get hepatitis C after medication or treatment?

Prior infection with HCV does not make you immune from being re-infected with the same or different strains or genotypes of the virus. Superinfection, or being infected with more than one HCV strain, is also possible if risk behaviours for HCV infection continue, like injection drug use.

TEN QUESTIONS ABOUT HEPATITIS C

WHAT ELSE SHOULD YOU KNOW

It is possible to have an active infection of at least two types of viral hepatitis. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection is a complex medical condition where the viruses replicate in the same host. In some instances, one virus is more dominant than the other, while there can also be cases where one virus either stimulates or suppresses the other's replication. Patients living with HBV-HCV coinfection are more prone to cirrhosis and severe liver disease.