Breadcrumb

- Home

- Infectious But Not Invincible

- Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis: An Old And Ongoing Epidemic

Tuberculosis (TB) has been around for thousands of years. It has been found in Egyptian mummies, and was also thought to be common in both ancient Greece and Imperial Rome.

However, it was only on March 24, 1882 when Dr. Robert Koch announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes TB.

Various major steps in TB history were made decades after Koch's discovery, from the Pirquet and Mantoux tuberculin skin tests in 1908, Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin 's (BCG) vaccine in 1921, to the development of TB drugs in the beginning of the 1940s.

Antibiotics were a breakthrough in TB treatment. In 1943, Selman Waksman, Elizabeth Bugie, and Albert Schatz developed streptomycin, and in November 1944 this drug was given to a patient for the first time. In 1951, the next drug for TB treatment, isoniazid, was discovered by scientists at Germany’s Bayer Chemical, and two pharmaceutical companies, Squibb and Hoffmann-La Roche. TB drug development continued and resulted in other drugs, such as pyrazinamide (1952), ethambutol (1961), and rifampin (1966).

How is Doctors Without Borders Responding to Tuberculosis?

Doctors Without Borders has fought against TB for many years. In 2019, Doctors Without Borders started 18,800 people on TB treatment, including 2,000 people with drug-resistant TB (DR-TB).

The settings in which Doctors Without Borders provides TB care vary widely. They include areas of chronic conflict, such as Chechnya; refugee camps in Chad or Thailand; prison settings in Kyrgyzstan; and countries with overburdened health systems such as Papua New Guinea.

The focus of the projects also varies: some concentrate on integrating HIV and TB services, such as in South Africa and Kenya; others offer treatment to patients suffering from DR-TB, as in Uzbekistan and Georgia; others reach out to particular populations who have little access to medical care, such as migrants in Thailand.

Doctors Without Borders is striving to improve diagnosis of all TB patients, by introducing tools such as a urine-based test called TB LAM, which is rapid, inexpensive, and easy-to-perform without electricity or instruments. Due to its lower sensitivity (which means that it misses many positive diagnoses) TB LAM cannot replace other tests, but in combination with GenXpert MTB/RIF and TB-LAMP, it can help diagnose TB cases in people living with HIV that would have otherwise gone undetected.

Another important tool is drug susceptibility testing (DST). The treatment of drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) requires DST to ensure people with TB disease are not treated with medicines against which their bacteria are resistant.

In terms of treatment, Doctors Without Borders is currently exploring different ways of ensuring patient adherence, and is committed to using fixed-dose combinations and quality-assured drugs in its programmes. Doctors Without Borders also aims to integrate TB and HIV services where possible, and to treat drug-resistant TB in appropriate settings.

There are quite a few challenges in addressing TB. Most of the drugs used to treat TB have been around for decades. Some were not even originally developed for TB use, or have toxic side effects. Another challenge is that TB treatment takes a long time, up to two years for DR-TB; and research into new, shorter, more effective drug regimens is urgently needed.

Doctors Without Borders is participating in two clinical trials, EndTB and PRACTECAL, to find new treatment regimens. Both trials enrolled their first patients by the end of March 2017.

DR-TB is a particularly worrying and growing problem in many of the places where Doctors Without Borders works. To improve chances of survival, Doctors Without Borders is conducting crucial research together with partner organisations to develop the evidence base for the therapeutic value of newer DR-TB treatments.

Most drugs to treat TB are old and have toxic side effects. But in the last decade, three new TB drugs were developed—bedaquiline, delamanid and, more recently, pretomanid—giving patients hope and treatment providers options.

When bedaquiline was first authorised for use in 2012, it was the first DR-TB drug to be developed in more than 40 years. But by late 2018, only 28,700 people had received it worldwide; that’s less than 20% of those who could have benefited from it.

Doctors Without Borders spoke out in 2018 to urge Johnson & Johnson (J&J), the pharmaceutical corporation that holds patents on bedaquiline, to take swift action to ensure affordable access to the drug for everyone who needs it to survive. In July 2020, after 120,707 people signed petitions urging the corporation to drop the price, J&J announced a reduced price of US$1.50, 32% lower than the previous lowest price. But this price is only available to a list of countries determined by J&J, and tied to purchase commitments made through the Global Drug Facility (GDF), an organisation run by the Stop TB Partnership that supplies TB drugs to low- and middle-income countries. Doctors Without Borders is still calling on J&J to further reduce the price of bedaquiline and offer it to all countries with a high DR-TB burden, so that more lives can be saved.

Through Access Campaign, Doctors Without Borders continues to call on and pressure governments and pharmaceutical companies to live up their commitments to address TB to save lives and reduce suffering and death from this terrible disease.

REAL PEOPLE, REAL STORIES

After losing her mother to MDR-TB five years prior, Ankita Parab learned that she too was infected with the disease. Following two years of arduous treatment, she was declared cured. Later, her brother also fell ill with MDR-TB.

© Abhinav Chatterjee

In 2016, when Ankita’s brother’s condition worsened, the doctor referred him to Doctors Without Borders’ TB clinic in Mumbai, India. He was quickly started on a treatment regimen that included the newer TB drugs. Ankita was also tested for TB through contact tracing, one of the preventive services Doctors Without Borders offers to all family members living with people with TB. The results were a terrible shock for her. Despite her earlier treatment, Ankita had developed XDR-TB – the most severe form of the disease.

Although the team in Mumbai started both siblings on the newer treatment at the same time, Ankita’s brother’s illness was too advanced and he died soon after. Her brother’s death and her new diagnosis were a double blow for Ankita. “He started his treatment at the same place, so if this can happen to him, it can happen to me as well – I’m not special. He took care of himself better than I ever did.”

It can be extremely difficult for people to complete long, toxic DR-TB treatment regimens without consistent encouragement and support, particularly when faced with personal hardships like the loss of a family member, unemployment or social exclusion due to other people’s fear of the disease.

- What is tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium tuberculosis that mainly affects the lungs.

In 2019, TB killed 1.4 million people, which makes the disease one of the top 10 causes of deaths worldwide from a single infectious agent. The World Health Organization (WHO), estimates that 10 million people globally fell ill with TB in 2019.

Of this number, two-thirds of people with TB are from these eight countries: India, Indonesia, China, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and South Africa.

- Is tuberculosis similar to pneumonia?

Pulmonary tuberculosis and pneumonia are two distinct forms of lung infection. But both diseases share some common signs and symptoms, such as cough and breathlessness, which is why they can be confused.

Pneumonia is inflammation of the lung tissue in one or both lungs. It can be caused by a bacterial infection, or by virus or fungus. It is an acute, rapidly progressive infection. If the pneumonia is caused by bacterial infection, antibiotics can help the condition improve in about 48 hours. The treatment itself usually lasts for several days, and in three or four days, patients will be free of symptoms. If it is viral pneumonia, the patient will need rest, plenty of fluids, and medicine for the fever.

Meanwhile, TB is caused by bacteria. Unlike pneumonia, the symptoms appear slowly and gradually. Even when treated, recovery from TB is slower compared to pneumonia. This disease also requires longer treatment, lasting at least 6 months.

- How is tuberculosis transmitted?

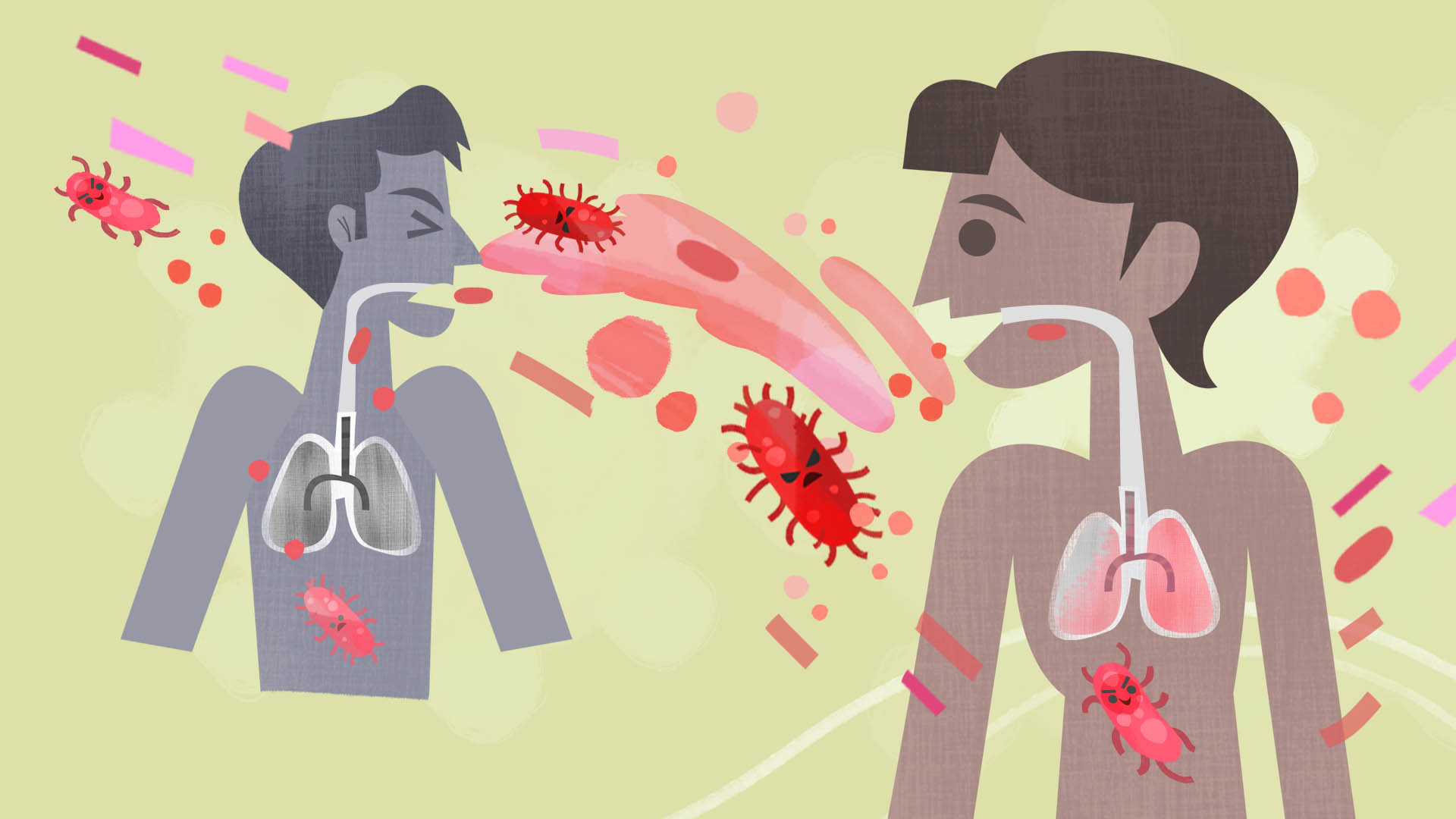

When someone who is sick with TB disease of the lungs or throat coughs, speaks, laughs, sings, or sneezes, the TB bacteria passes from them through the air. When another person breathes them in, the bacteria can settle in the lungs and begin to grow.

People with TB disease are most likely to spread it to people they spend time with on a daily basis, such as family members, friends, and co-workers or schoolmates.

- Can tuberculosis kill you?

This disease is infectious, and can be fatal if not treated properly.

If someone with TB disease fails to finish the recommended treatment, TB bacteria can also develop into a drug-resistant strain (DR-TB). This means that it is more difficult to treat than drug-susceptible ones.

Another factor that complicates treatment is if a TB patient is immunocompromised, or has another condition like HIV or diabetes.

- What does tuberculosis do to the body?

When the bacteria that causes TB enters the lungs and infects someone, the body will detect the invasion and mobilise its immune cells. This includes macrophages or cells whose job is to neutralise the bacteria and other harmful organisms. If this process of neutralisation works, the person will have latent TB. But if the immune system loses the battle and the bacteria multiply, then the person becomes sick with TB disease.

There are two types of TB conditions: latent TB infection, where TB bacteria are neutralised and live in the body without making you sick and without any symptoms; and TB disease, when TB bacteria become active in the body, multiplying and making you sick.

Many people who have latent TB infection never develop the disease. But in people who have weak immune systems, the bacteria can become active, and TB disease can develop.

- When should you meet the doctor or seek treatment?

Common symptoms of active lung TB include cough that lasts more than three weeks, sometimes with sputum and blood, chest pains, weakness, weight loss, fever, and night sweats.

If you have any of these symptoms, see your doctor and get tested.

- Who is most prone to tuberculosis?

Anyone can get TB. But some are at greater risk, such as those who are in prolonged close contact with someone who's infected, and people living in crowded conditions.

There is also greater risk of TB among those who have conditions that weaken their immune system, such as diabetes. Another risk factor is poor health or poor diet due to lifestyle and other problems, such as drug misuse, alcohol misuse, or homelessness.

- Can tuberculosis be eradicated?

Despite being a preventable and curable disease, TB still claims millions of lives each year. Access to better treatment and diagnosis in poorer countries is an ongoing obstacle. Emerging drug-resistant strains of TB—when first-line drug treatment can no longer kill the TB bacteria—are also hampering efforts to stamp out the disease.

- How can you prevent or treat tuberculosis?

If you have latent TB infection, you may need medication to reduce risks of developing TB disease later.

If you have TB disease, you need to take several medications for at least six months and possibly as long as one year to kill all the TB bacteria. Ethambutol, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, and Rifampin are four medications most commonly used to treat TB disease. It is very important that you complete the entire course of treatment (medicine is often given in regular intervals or even on a daily basis - it's easy to finish the medicine, but hard to complete the entire treatment) , and take the medications exactly as prescribed by the doctor. Otherwise, the bacteria that are still alive may become difficult to treat and may result to drug-resistant TB/DR-TB.

- Can you still get tuberculosis after medication or treatment?

It’s possible to catch TB more than one time. If someone is already clear of TB, but later breathes in TB bacteria, re-infection can happen. TB can also recur as a result of a relapse of a previous infection.

You should always take new TB symptoms seriously, and get them checked by a doctor, and undergo treatment if advised.

TEN QUESTIONS ABOUT TUBERCULOSIS

WHAT ELSE SHOULD YOU KNOW

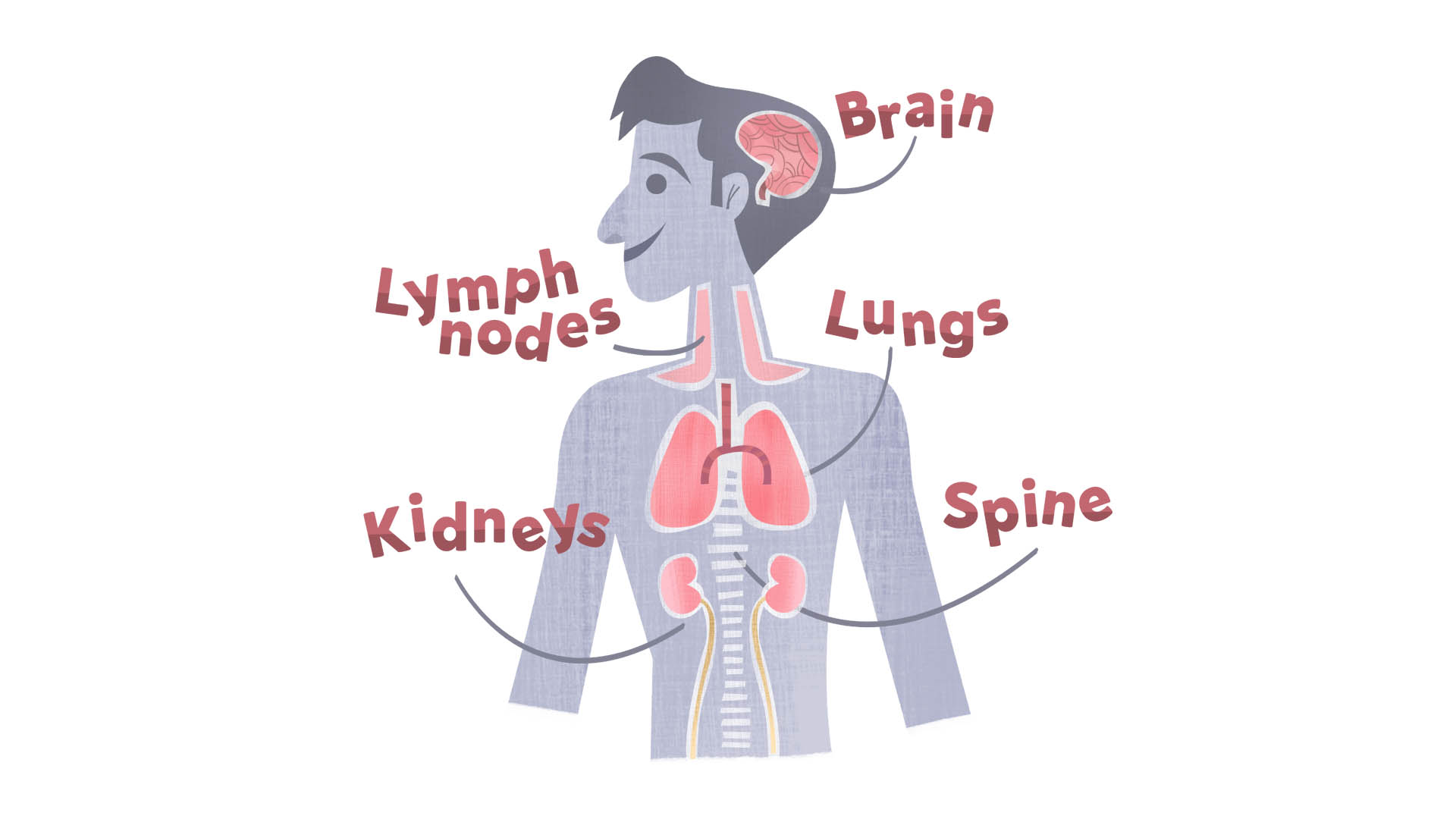

Even though TB most commonly attacks the lungs, this disease can also occur outside the lungs (extrapulmonary), affecting other parts of the body including the spine, kidneys, brain, and lymph nodes. In general, the infection progresses slowly.