World Refugee Day 2023: #ImagineRohingya - A photo story

© Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

On this World Refugee Day 2023, Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is launching the first episode of a monthly photo essay picturing the situation in the camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, as experienced by the Rohingya and witnessed by Doctors Without Borders.

‘I don’t know what the life of a man is. All I know is here.’ - Jamal, Camp 2W, 01/06/2023. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

The Rohingya are a stateless ethnic group, most of whom are Muslim. They have lived for centuries side by side with the Buddhist community in Rakhine state, Myanmar, but following repeated cycles of targeted violence and continuous loss of their rights, nearly one million Rohingya people fled to neighbouring Bangladesh. The camps of Cox’s Bazar are now the world’s largest refugee camp.

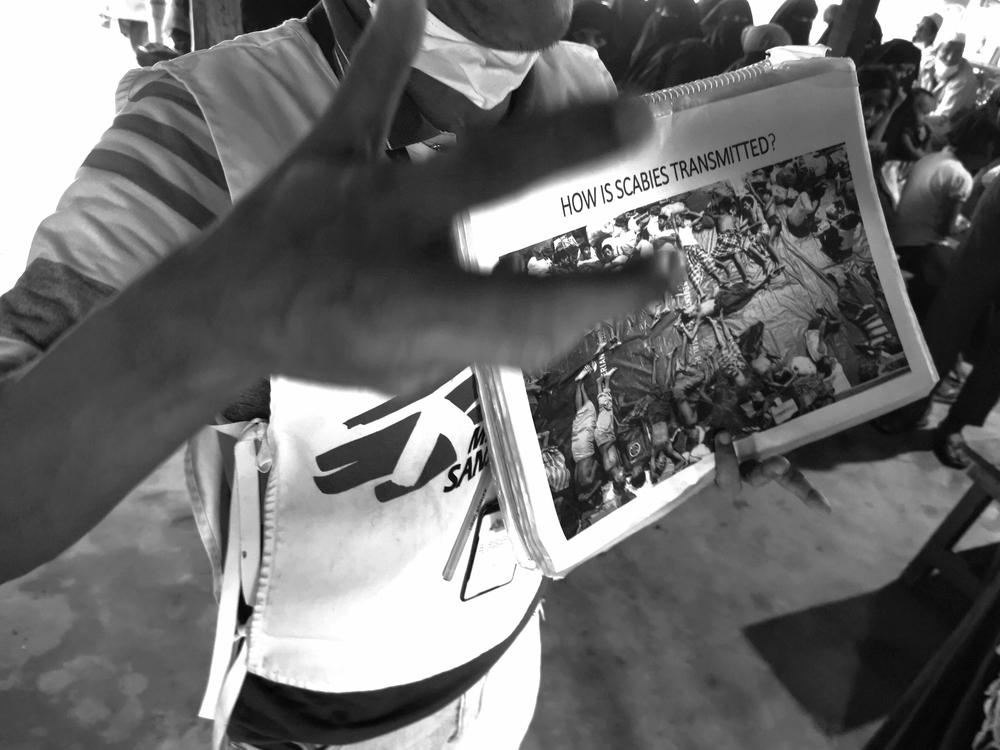

So far, the year 2023 has been very challenging once again for the Rohingya refugees who live behind wires. The least amount of funding went into the Rohingya refugee crisis response in the past five years in 2022. Consequently, the Rohingya have so far faced two cuts to their food rations this year. They also face disease outbreaks because of insufficient water and sanitation facilities, including a so far uncontrollable scabies outbreak that Doctors Without Borders first sounded the alarm about more than a year ago. Scabies is a skin disease caused by a microscopic mite that burrows into the upper layer of the skin where it lives and lays its eggs – this causes intense, relentless itching, and a pimple-like rash in most people. Scabies usually affects children but if left untreated it can quickly spread to a whole family.

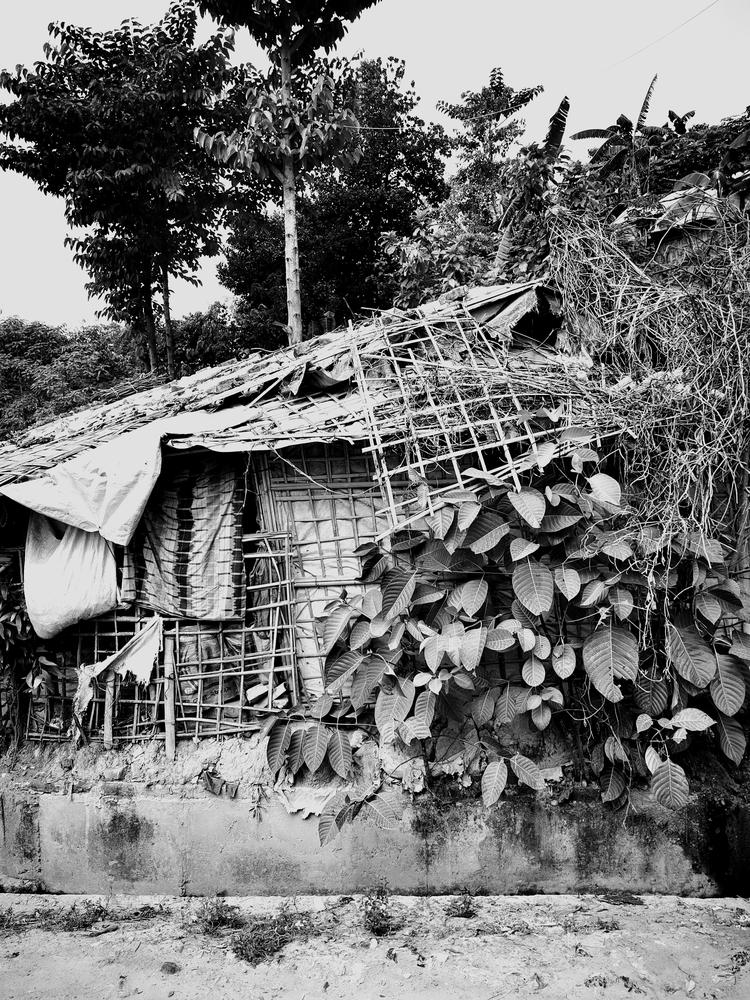

On May 13, a strong cyclone, called ‘Mocha’, hit the camps, affecting thousands of families and damaging bamboo shelters in some areas. A few days after the cyclone passed, we met Jamal in camp 2W, next to Doctors Without Borders’s Kutupalong hospital. Jamal has been living with his wife and two young children in a bamboo shelter for years. When the cyclone hit, he had no other option than to stay inside and wait for it to pass, hoping for the best. Jamal is also a photographer. He documents life in the camps, “hoping to raise awareness on living conditions of the Rohingya refugees”. After the cyclone hit, he went out walking around the camps to document the damage with his phone “to show the world how people are dealing with it”, he said.

‘It is not by choice that we rely on humanitarian assistance, you know? But here, remember, we are not authorised to work. Not a choice, you know.’ - Rahim, Kutupalong Hospital, 03/2023. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

While living with no prospects of safe returns to their homes in Myanmar, the Rohingya are not allowed to work or receive a formal education and have no alternative but to rely on humanitarian assistance to meet their basic needs. They struggle with uncertainty about their future, for themselves and their children. In 2022, the least amount of funding in the past five years went into the Rohingya refugee crisis, affecting provision of basic services such as food rations which have been cut twice this year.

“The ration cuts are just another blow. The common word is “we take whatever we get”. There is nothing we can do about it. The situation here is even more tense this year, not only because of the food ration cuts. In 2020 they imposed fences, we cannot work legally in Bangladesh, so people are taking the risky route to Malaysia. It is better to die with hope, than to live here without any. With the ration's cuts, on an empty stomach, people will try anything, whatever way possible” said another woman met on March 2nd, 2023, in the camps.

‘Yes, we were afraid during cyclone Mocha. A tree fell on our shelter but I fixed it myself. Our shelters are so weak, man.’ - Abul, Camp 2E, 31/05/2023. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

The month of May has proven very challenging again in the world’s largest refugee camp in Bangladesh, where close to one million Rohingya refugees live behind wires. With monsoon season starting earlier than expected, a strong cyclone, called ‘Mocha’, hit the camps on May 13. Damages caused by the cyclone exacerbate the living conditions of the Rohingya as they continue to be exposed to frequent risks of devastating natural disasters without the possibility to leave the camps to take shelter in safer locations.

‘When asked about their happiest memories from Myanmar, women always respond with something about their home.’ - A Rohingya volunteer, Rohingya Cultural Center, Camp 18. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

The Rohingya are a stateless ethnic group, most of whom are Muslim. They have lived for centuries side by side with the Buddhist community in Rakhine state, Myanmar, but following repeated cycles of targeted violence and continuous loss of their rights, nearly one million Rohingya people fled to neighbouring Bangladesh. The camps of Cox’s Bazar are now the world largest refugee camp.

While living with no prospects of safe returns to their homes in Rakhine state, our patients and the larger Rohingya refugee community often tell us about their longing for their life in Myanmar.

‘I have a bag ready in case of a fire (…). Incidents, fires, cuts in food, it all keeps me awake at night. I can see the impact in the way I behave and talk to others.’ - Rihanna, Camp 09, 01/03/23. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

Rihanna lives in the world’s biggest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. She shares a bamboo shelter with seven other people: her mother, her sister and their children. On March 7, 2023, a massive fire broke out in a nearby camp, destroying hundreds of shelters. We met Rihanna a few days after the dramatic incident. She shared about the vulnerability and fragility of living conditions in the camps, being exposed to the elements and feeling unsafe.

Some of the most common reasons to visit the mental health program in our Doctors Without Borders facilities is anxiety linked to the situation of hopelessness, lack of safety and uncertainty about the future. Already this year, Rohingya have endured two food ration cuts due to funding reduction affecting the Rohingya refugee crisis. Cuts in food rations increase risk of malnutrition and other deadly outbreaks while the Rohingya are almost fully dependant on food assistance. There has also recently been a cut to soap rations, at the same time as a health sector survey conducted in the camps showed a 40% prevalence of scabies in the camps.

‘It is unfathomable that a scabies outbreak should have been allowed to go on for this long.’ - Karsten Noko, Doctors Without Borders Head of Programmes, Bangladesh, 06/2023. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

Nearly 40 percent of people in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh have scabies according to the results of a prevalence survey conducted by the camps’ health sector this year. In some camps this figure is as high as 70 percent. This reflects what Doctors Without Borders has seen in our clinics where we have conducted over 200,000 consultations for scabies since March last year. Scabies causes intense, relentless itching, and a pimple-like rash in most people. Scabies usually affects children but if left untreated it can quickly spread to a whole family.

Reacting to these results, Karsten Noko, Doctors Without Borders Head of Programmes in Bangladesh, said on June 7, 2023:

“It is unfathomable that a scabies outbreak should have been allowed to go on for this long, causing pain, suffering and indignity to so many. These are people who were forced from their homes by persecution and violence. They live in camps behind fences. They have no legal status and no right to work. They have no choice but to depend entirely on humanitarian aid. Yet repeated funding cuts have reduced again and again the assistance available to them.

These figures show the consequences. We strongly call on the health sector, donors and all other actors who can help make this happen, to develop and implement a comprehensive, multi-pronged response that finally addresses both the treatment and prevention of scabies on a large scale, and the appalling water and sanitation conditions that have allowed this outbreak to grow out of control.”

‘We do not have enough space. I tried my best to maintain hygiene standard, but it is hard. Still, we share bedding, we share clothes, everything. Now, we share scabies too.’ - Taher, Camp 15, 02/03/2023. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

Scabies, a skin disease, is on the rise among Rohingya refugees living in camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. The sharp increase in scabies cases is directly linked to the living conditions in the camps, where people share small, cramped spaces and some have inadequate access to water to meet their daily needs at the same time as having their monthly soap ration cut earlier this month.

For over a year now, Doctors Without Borders has been trying to manage this outbreak, but the number of scabies patients has surpassed Doctors Without Borders’s capacity to respond alone.

Ajmot Ullah, another 26 years old patient suffering from scabies, told us in March 2023:

“My wife had scabies a couple of years ago. She went to a Doctors Without Borders facility, received treatment and ultimately got better. Now my whole family suffers from scabies again. Our four-year-old son has had it since last December. First, he had rashes on his hands, which then spread to his whole body. We spent money on doctors and in local pharmacies nearby. He eventually got better, but scabies hit him again very quickly. He doesn’t sleep much; cries a lot from pain, and his whole body is itching, especially at night. My other two sons are also suffering from scabies now, while my wife and I have scabies symptoms again. It has become a nightmare for my family”.

‘No special plan for next year. No. Hope would be great, but above all, some education for my kids would be best.’ - Jamal, Camp 2W, 01/06/2023. © Olivier Malvoisin/MSF

Rohingya have no prospects of any imminent safe returns to their homes in Myanmar. They are contained to the camps in Cox’s Bazar. They have no permission to work or travel and have little access to education. This makes them almost entirely reliant on services provided by humanitarian actors in the camps, even if they would have preferred to take responsibility for their own future. We have a responsibility as humanitarian community to ensure sustained funding and resources to provide Rohingya with dignified and safe living conditions until their situation changes and they can take control over their lives.