Ukraine: Caring for the vulnerable people left behind by the war

Drawings at a metro station in Kharkiv. Ukraine, April 2022. © MSF

Doctors Without Boders' Dr Natalie Roberts has just come back from Ukraine, where she witnessed the severe challenges facing some of the most vulnerable people in the areas that were controlled by the Russian forces or otherwise inaccessible for a while, and are now under Ukrainian control and accessible for our teams.

My first impression of the Kyiv region was that of an exodus. In early March, as we headed along the road from the west towards the capital, long lines of cars were moving in the opposite direction. Most of them had the word “children” written on the windscreen, in the hope it would protect them from Russian bullets. Each one was filled with people, belongings and pets. If not for the air-raid sirens, the checkpoints and the snow, one might have imagined they were families heading away on holiday.

I soon realised that these people were the lucky ones. Young people, women and children and people with access to a car and money were able to flee to western Ukraine and neighbouring countries.

A market destroyed by a fire caused by Russian bombing in Kharkiv. Ukraine, April 2022. © Adrienne Surprenant/MYOP

That is why even in areas that were occupied by Russian forces such as Makariv, Borodianka, Irpin and Bucha, there remained a significant number of inhabitants.

The world was shocked to see the images of civilians who were massacred in the streets of Bucha, but special attention must now be paid to the survivors. For a month, it was impossible for anyone to enter these areas and it was very difficult to leave. Older people living alone, the infirm and the disabled simply did not have the opportunity to flee.

Those who ventured outside risked being shot at by Russian soldiers or tanks. Electricity, gas and water supplies were cut off. Hospitals and health facilities were damaged or destroyed and the staff fled, cutting off all access to healthcare. Hypothermia, stress and the lack of access to care provoked acute decompensation of chronic diseases, resulting in people having heart attacks and strokes. Many health workers suspect that the mortality related to these diseases among this particularly vulnerable group of people will in fact be higher than that directly related to the violence.

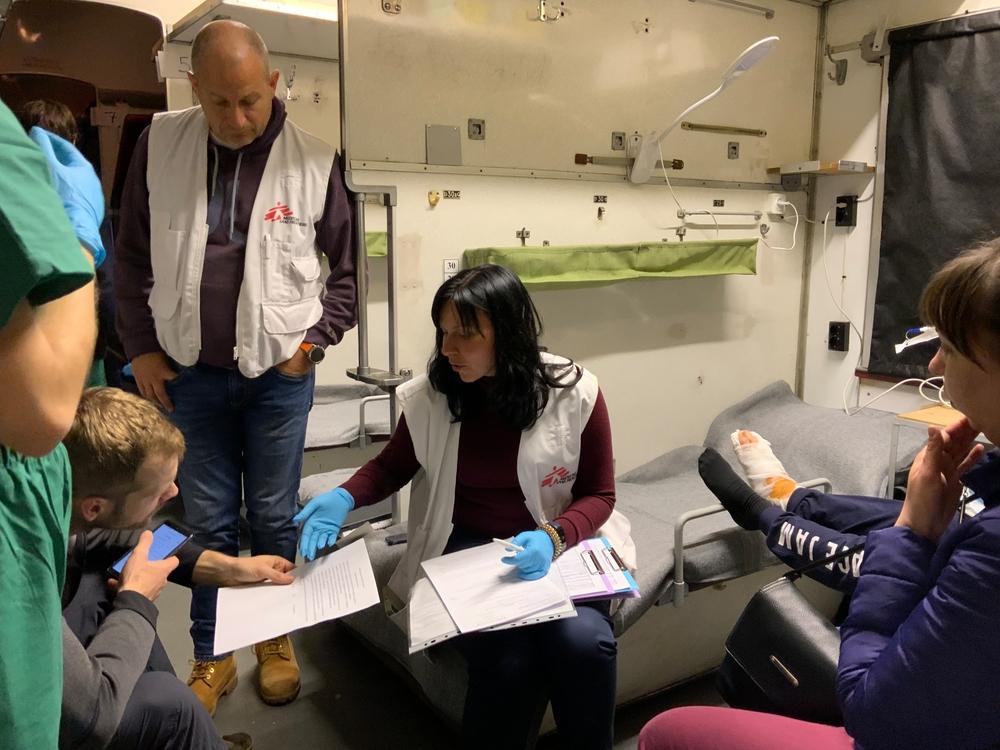

In areas that are now back under Ukrainian control, such as Makariv, Borodianka and the villages north of Fastiv, Doctors Without Boders teams have begun to support local doctors and authorities to offer medical care, trying to find and stabilise sick people before transferring them to the hospital in Fastiv. Doctors Without Boders is also helping the hospital to cope with the increased demands by donating medicines and equipment and organising visits of a physiotherapist and a psychologist. We plan to extend these activities to areas further north of Kyiv and to Chernihiv, where access is now possible.

Makeshift beds lining the platform in one of Kharkiv's Metro stations. Ukraine, April 2022. © Lisa Searle/MSF

To the south of Kyiv, in Bila Tserkva, Hrebinky and Ksaverivka, a large part of the population has fled, fearing the possibility of a rapid advance by Russian troops. Once again it was the most vulnerable people, the elderly and the sick, who were left behind. Hospitals and health facilities were ordered to stop all non-emergency care and prepare themselves to receive the wounded.

Access to healthcare, including primary care, has become extremely difficult. Pharmacies have closed or no longer have basic medicines in stock. The sale of alcohol was banned so alcoholics have begun to suffer from acute withdrawal, a situation that can lead to death. Social workers, lacking access to fuel, have resorted to using bicycles, but frequent curfews, movement restrictions and checkpoints prevent them from reaching housebound and bedbound people as often as they need to. These same ocial workers pointed out the paradox that while functional hospitals remain empty, waiting for the injured, the sick are condemned to stay at home.

Some people have also remained in these areas because of chronic illnesses such as kidney failure or cancer, which make them dependent on dialysis or chemotherapy. Without assurances that they will be able to access these services if they flee to the west of the country or abroad, they are trapped, and their relatives are often trapped with them.

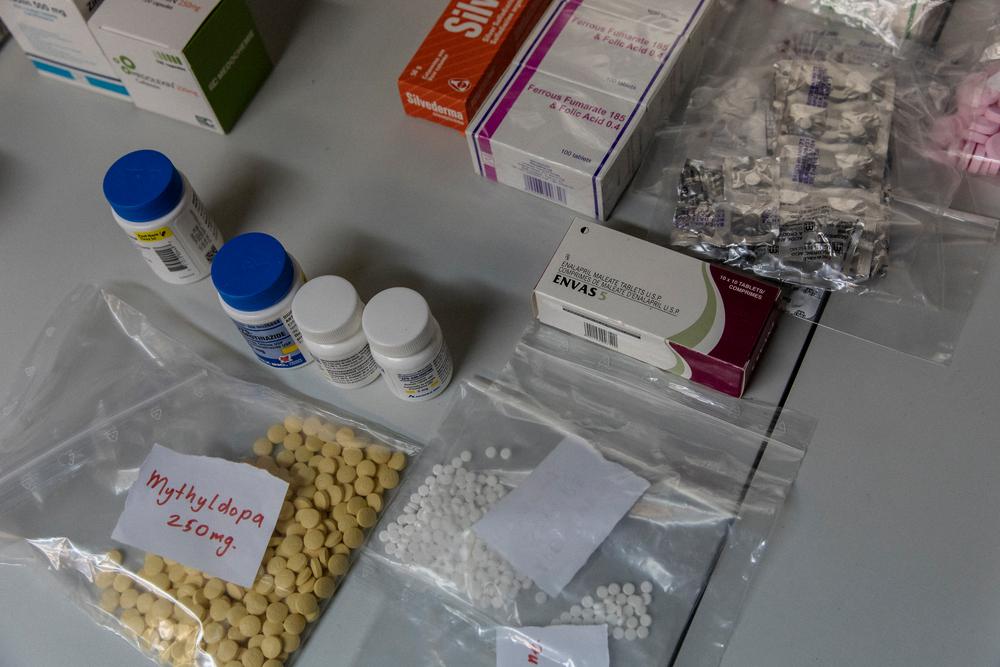

Medecine is ready to be given to patients at an Doctors Without Boders mobile clinic in a metro station where people hide form bombings and now live, in Kharkiv. Ukraine, April 2022. © Adrienne Surprenant/MYOP

The director of Nezabutni, a Ukrainian charitable foundation that supports older people and their carers across the country, told me that even in places that are being heavily bombed, families of people with dementia often choose not to take cover when the alarms sound, as the disorientation and distress provoked by being confined to a crowded bunker each time is simply too traumatic for the most fragile. They prefer to hope that it was a false alarm than risk an irreversible decompensation of their loved one’s condition.

During my time in Ukraine, I was impressed by the solidarity shown by the carers who refused to allow these people to be abandoned. Time and again I heard people explain that they could have left but instead were staying to help the most vulnerable. The mayor and residents of Fastiv who, thanks to an impressive mobilisation of volunteers, were already hosting displaced people from nearby occupied towns such as Makariv and Borodianka, were also trying to find a way to evacuate the remaining population from these areas.

Social workers, often middle-aged women with families of their own, were working 24/7 to try to identify and reach every single person who was stuck at home. Volunteer networks were trying to source medicines in the pharmacies and deliver them to the homes of the stranded, along with food and other essential goods. Staff in old people's homes stayed on duty, even when they were terrified that the fighting was closing in.

This mobilisation of civil society that I saw in the region of Kyiv is also being replicated in areas like Chernihiv, Kharkiv and other parts of the east.

Doctors Without Boders’s third medical train referral in Ukraine: arrival in Lviv. Ukraine, April 2022. © Maurizio Debanne/MSF

So, what can organisations like Doctors Without Boders do about this situation? Nine million people in Ukraine are over 60, and many have been isolated since the war began. We need to pay special attention to them and their caregivers.

We can support the evacuation of elderly and disabled people who find themselves close to the front lines to suitable accommodation in safer areas of the country. That same accommodation could house people who have experienced catastrophic trauma in places such as Bucha. Doctors Without Boders can play an important role in collaborating with Ukrainian social services to establish and support these structures and to assist with medical evacuations. We can also support volunteer-run pharmacies to ensure that they have adequate supplies of medicines, including those for chronic illnesses.

Doctors Without Boders' fifth medical train referral arrived Lviv. Ukraine, April 2022. © Avril Benoit/MSF

In addition, Doctors Without Boders is planning to financially and technically support a digital platform developed by Nezabutni which would allow elderly people and their families to benefit from teleconsultations and from access to information on the specific assistance that is available to them, even in such an uncertain and unstable context.

It is through agility and creativity that an emergency medical organisation like Doctors Without Boders can be most useful in the rapidly changing context of war. Long-term needs are starting to emerge that means that we must engage now, especially in support of all those vulnerable people 'left behind'.