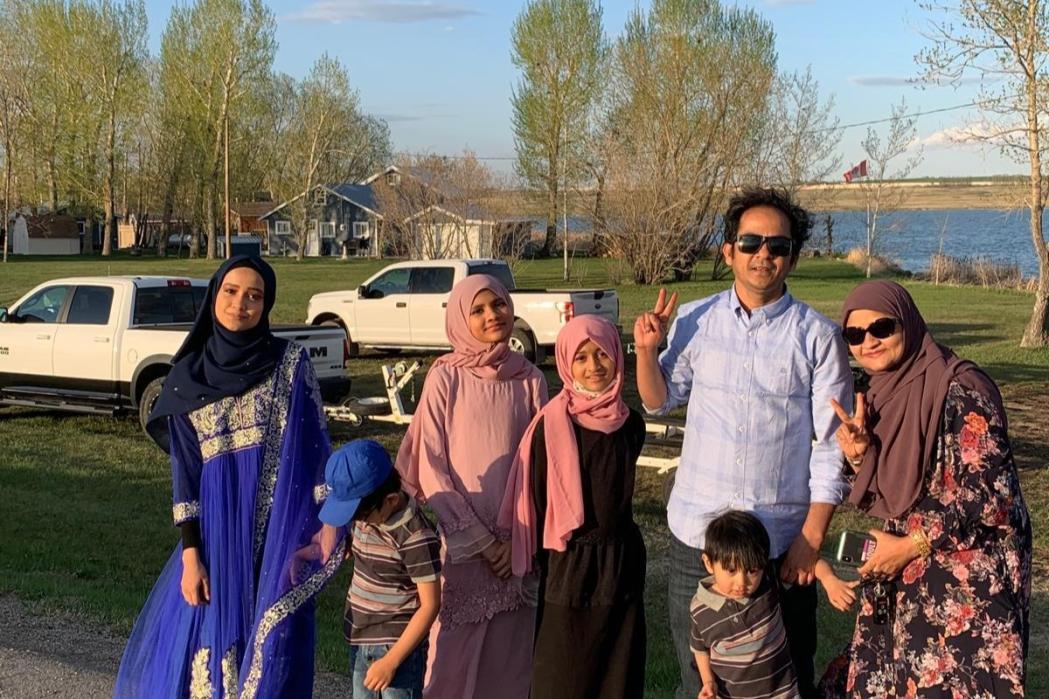

Mohd Ayas and family in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. © Private

Ayas was a health educator while Sandar moved from health education to office administration and finance. The couple’s lives were turned upside down when violent intercommunal clashes broke out in June 2012. Hundreds of people were killed, and thousands of Rohingya families fled their homes. Doctors Without Borders was forced to suspend most of its medical activities in Rakhine state.

Doctors Without Borders was the largest organization providing medical care to the Rohingya. Many no longer had access to healthcare after the Doctors Without Borders clinics closed. TB and HIV patients were no longer able to get their medication. The government-owned hospitals did not admit Rohingya patients.Ayas, a Rohingya volunteer

Already challenging before the clashes started, life became even more difficult for the married couple and their three young daughters. For several months, they had no information about the whereabouts of their family members, who were in a different town. Nighttime arrests of Rohingya by government soldiers and police became frequent.

The family spent most nights in the facilities of Doctors Without Borders and another NGO Ayas had volunteered for, hoping it would be safer. When Ayas learned that his name was on a police blacklist because of his volunteer work with NGOs and that he could be arrested at any time, he knew he had to leave Myanmar.

“I was very depressed and anxious. I decided to flee to neighboring Bangladesh and return if the situation gets better,” he says. Five months later, when the couple realized that things were not improving, they decided that he would go to Malaysia and that the rest of the family would follow later.

After several months, Doctors Without Borders was able to resume some of its medical activities in Rakhine, but the situation for Rohingya staff volunteering with foreign NGOs remained dangerous.

A perilous journey to Malaysia

In November 2013, Sandar decided to join her husband in Malaysia. With her three young children – nine months, four, and eleven years old at that time – she boarded an overcrowded boat with more than 2000 other Rohingya refugees. The 13-day boat ride from Myanmar to Malaysia, with a short stop in Thailand, was harrowing.

“They did not give us any water or food. People were dehydrated. The children were crying all the time. There were no diapers for the babies. It was very hot. We couldn’t sleep. There was no washroom. People were defecating on the floor where we were sleeping,” Sandar remembers.

When Sandar and the children arrived in Malaysia, they were traumatized by the journey. They needed to be hospitalized to be treated for skin diseases, sunburn, and dehydration.

Life in Malaysia

Reunited with Ayas, the family first lived in Malaysia’s capital Kuala Lumpur. Living without legal documents before they were recognized as refugees by the UNHCR, they still did not feel safe. “We were still scared of getting arrested. But unlike in Myanmar, at least we knew they wouldn’t kill us,” says Ayas.

In 2015, they heard that Doctors Without Borders had started a project in Penang to support Rohingya refugees, first launching mobile clinics and later implementing a referral system and opening a clinic. Ayas and Sandar decided to move to the Malaysian island, where they became part of the Doctors Without Borders team as facilitators between Rohingya patients and hospitals.

Rohingya came from all over Malaysia to Penang to get medical support from Doctors Without Borders, especially pregnant women. The Doctors Without Borders clinic became increasingly busy, also with patients from other communities.Ayas, a Rohingya volunteer

Life in Malaysia had many challenges. Sandar gave birth to two more children. One of them, a boy, was born in Kuala Lumpur with a medical condition that required surgery. “The hospital initially did not want to operate on our son because we are refugees, and because they thought he would die anyhow. We had to pay a lot of money so that they finally agreed to the surgery,” says Sandar.

Most of the couple’s allowances was spent on paying rent, medical bills for their son, and the private school their older children were forced to attend as Malaysian public schools did not accept refugee children. Due to these difficulties, they longed to be resettled. Eventually, UNHCR facilitated their resettlement to Canada.

Move to Canada

At the end of 2019, the family moved to Calgary, and they now live in Edmonton. Sandar and Ayas have attended professional development courses, have part-time jobs, and volunteer to support other former refugees in Canada.

After being stateless for most of their lives, due to the stripping of the citizenship of Rohingya people in Myanmar, having Canadian citizenship means they can now move around freely for the first time in their lives.

Mohd Ayas and family in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Sandar was able to visit her mother and other family members in Myanmar’s capital Yangon earlier this year, where they have fled from Rakhine. They hadn’t seen each other for more than a decade. “My mum and other family members suffer from depression and anxiety. My father died from shock after the latest outbreak of violence in Rakhine in 2017.”

The couple’s oldest daughter, the only child who still remembers the traumatic boat ride to Malaysia, is studying for a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology. “She wants to go to medical school after she graduates,” Ayas says proudly. “She says she wants to work with Doctors Without Borders in Myanmar or Malaysia one day.”