Mental health in Yemen: “The number of severe cases is astonishingly high”

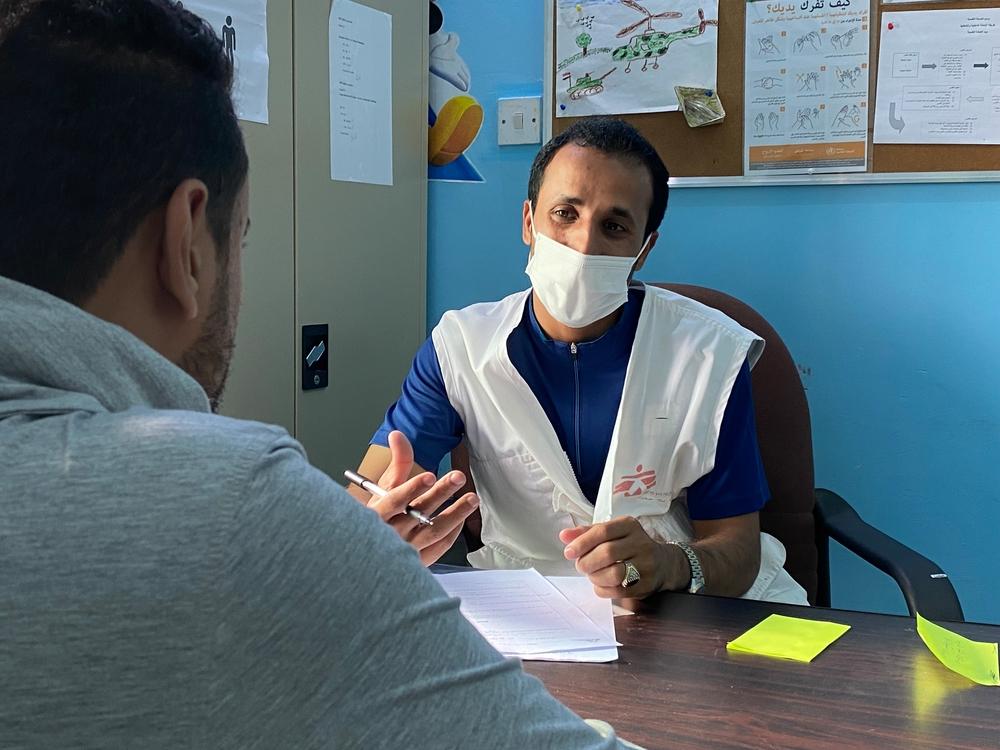

A psychologist conducting a counselling session with a patient at mental health clinic supported by Doctors Without Borders at Al-Gamhouri Hospital in Hajjah. Yemen, 2021. © Nasir Ghafoor/MSF

Now in its seventh year, the crisis in Yemen is no longer headline news. But the conflict continues to have a devastating impact on people’s wellbeing, and on their mental health in particular. Antonella Pozzi, Doctors Without Borders' Mental Health Activity Manager in Hajjah tells the complex needs in the region.

What is happening now in Yemen?

The crisis in Yemen has been going on for more than six years, and it’s no longer a top story in the headlines. Fortunately, in Hajjah governorate we see fewer casualties as a result of fighting compared to the early days of the conflict. However, the war is not over. There are of course still conflict-related deaths in the country. What doesn’t usually receive attention, though, is the impact that this conflict has had on people’s wellbeing, and their mental health in particular.

What kind of mental health issues does Doctors Without Borders see?

In the city of Hajjah, about 120 kilometers northwest of Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) supports Al-Gamhouri hospital to provide specialized mental health services. The range of conditions that we treat is very large; there are people suffering from anxiety and insomnia, and then we see patients presenting with severe pathologies such as psychosis, depression, bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In our service we regularly see patients following suicide attempts. A suicide attempt can be provoked by a variety of circumstances. Severe symptoms of psychosis can manifest as auditory hallucinations that tell the patient to hurt him or herself, or a patient might be suffering from severe depression. In the case of psychosis, it is important to understand the subjective experience of the individual, since hallucinations can seem very real and create a great deal of suffering.

Why are there so many patients suffering from mental health conditions?

Mental wellbeing is very much affected by external factors. The more intense someone’s circumstances are, the more their wellbeing will be impacted. Living in a context of war means being exposed to constant stress for a long period of time. Armed conflict in Yemen has not only affected people’s physical health: it has reduced their access to healthcare, education, and food, it restricts their freedom of movement and denies them the freedom to express themselves. This creates serious mental health disorders.

Patients with mental health issues in Yemen are no different to others experiencing conflict around the world. But 45% of the patients we see in the Doctors Without Borders mental health clinic are severe cases. The number of severe cases is astonishingly high, especially taking into account that worldwide, and even in conflict settings, the number of patients presenting severe mental health conditions should not exceed 5.1% of the total cases, as defined by the World Health Organization in 2019. The lack of services in the area of Hajjah city and for several kilometers around it means that all severe cases in the area are directed towards our services, which may explain the numbers.

- Hamdan story: Mental health disorders aren’t a choice

Hamdan Saleh had worked happily in the administration department of the Yemeni security forces for years. But at the start of the civil war in Yemen, he became one of the hundreds of government employees who had their salaries stopped. His pay was the only source of income for his family. Their sudden financial difficulties, alongside the worsening conflict, led Hamdan to develop mental health issues. Hamdan began to suffer from psychosis and feelings of paranoia.

“I started believing that everyone was conspiring against me, trying to harm me. I had hallucinations too, hearing and seeing mystical creatures telling me to do things. Telling me to die. One day I poured gasoline on myself to set myself on fire. I changed my mind at the last moment by thinking of my children.”

With no knowledge or understanding of mental health care, Hamdan’s family turned to spiritual treatment. However, it did not work.

“Hamdan was referred to the Doctors Without Borders mental health clinic at Al-Gamhouri Hospital in 2019 after he had already suffered from the disorder for years,” says Doctors Without Borders psychologist Rasmia Mohammed Ali. “He is another example of how the conflict has affected people’s lives economically and socially, leading to severe mental health issues.”

“While the lack of services for mental health care is a problem, people’s limited understanding of such conditions is also a challenge. There are patients who feel better once they start taking the right medication and so leave the treatment considering themselves fine. This could lead to relapse. Hamdan was one who struggled to consistently take his treatment, but he is now fully treated and discharged from the clinic.”

Hamdan is now a farmer back in his village. He grows corn and wheat. He feels better, and his family and social life are back to normal. It has been a month since Hamdan last came to the mental health clinic with his son. As he walked out of the clinic, Hamdan said he hoped he would never come back here again.

“I experienced some side effects of the treatment. But I had to take medicines to make myself better. If I had a choice, I would have never taken the medicines, but mental health disorders aren’t a choice.”

- Hafsa story: I still fear something could happen to my children

The memories of her hometown of Harad still haunt Hafsa. At around nine o’clock one evening in 2016 an airstrike hit her neighbourhood. Her children were at their mosque praying and only Hafsa and her husband were at home. Now, living over 150 kilometres away, Hafsa remembers how her house trembled and the heavy sound as a bomb struck a nearby gas station. Many of the houses nearby collapsed and more than 250 people were either injured or killed.

The external part of Hafsa’s house was badly damaged, but this was nothing compared to the loss the family suffered that night.

Hafsa’s husband already had a heart condition and, while he was not physically harmed during the airstrike, the shock of the explosion caused his heart to stop. Hufsa took him immediately to hospital, but the doctors told her that he had died some hours earlier.

“We moved from Harad to Hajjah. It’s been more than five years since I visited my hometown, where I lived the first 50 years of my life. Harad is very close to the frontline and nobody lives there now. We are not allowed to travel there. I was told the only things one can find there are landmines.”

Hafsa developed psychosis following this traumatic incident. She began to have flashbacks of the airstrike and could not stop thinking about how it had taken everything from her. She also developed a sense of paranoia, fearing all the time that something terrible could happen again.

“I do not want to have all my children together in one room. If something happens, everyone together would become victims of bombs or airstrikes. I do not like letting my children go out. When they do, I ask them to stay in contact with me regularly. I fear something could happen to them,” adds Hafsa.

Following the death of her husband and their move to Hajjah, life has not been easy for Hafsa and her family. There is no income for her family, and they are entirely dependent on humanitarian aid. Hafsa came to know about mental health services from her granddaughter, who attended a routine mental health awareness session at a hospital. When she learned about the symptoms that might point towards a mental health disorder, she realised her grandmother could be a patient.

Hafsa was not the only one in her family who developed mental health issues. Her daughter developed psychosis and attempted suicide by setting herself on fire. She was severely burned and needed weeks of treatment for her injuries. Alongside this, she was also treated for psychosis at the Al-Gamhouri Hospital mental health clinic in Hajjah, which is supported by Doctors Without Borders.

“We treated both Hafsa and her daughter for psychosis developed following their experiences during and after the airstrike. We see a number of such patients. The conflict and its consequences on people’s lives are one of the leading causes of mental health disorders,” says Doctors Without Borders psychologist, Rasmia Mohammed Ali.

*The name of the patient is changed.

How many people need medical support?

Authorities have identified more than 9,000 patients in the Hajjah area who are in need of mental health services. The actual number is probably even higher, since mental health needs tend to be underestimated. People often come to our clinic from distances of more than 100km to access our services, and it indicates the high needs across the country.

Because of the war, the population in Hajjah is accustomed to high levels of violence. People here are very resilient and their tolerance to adverse circumstances is very high. This means that they arrive at mental health consultations only if a mental health issue has become very obvious and disruptive to the patient and his loved ones. For instance, a family might only become alarmed and seek help when a patient is at the point of becoming agitated or paranoid and is threatening to hurt others.

The war and the lack of mental health services in the area has increased the prevalence of these sorts of conditions. In March, June, and July (for example) of this year, more than half of new patients seeking help at the Doctors Without Borders clinic presented with severe mental health disorders.

The treatment of severe mental health conditions is very challenging here. In Yemen the first option for people with mental health symptoms is to seek spiritual treatment. The consequence of this is that sometimes, by the time that patients arrive at our clinic, they have been exposed to ineffective and sometimes harmful practices that exacerbate their symptoms. Seeking spiritual treatment instead of going to a health facility indicates the lack of mental health awareness among the population, another pertinent factor in this context.

Hamdan and his son Hashid share a smile as Hamdan bidding farewell to the medical staff after completing his treatment at waiting area of the mental health clinic supported by Doctors Without Borders at Al-Gamhouri Hospital in Hajjah. Yemen, 2021. © Nasir Ghafoor/MSF

What can be done to improve the situation in Hajjah?

It is essential to try to help the population to understand what mental health conditions are, and how to recognise them. This would give patients and their families at least some of the tools to handle severe conditions. In the case of psychotic patients presenting severe signs of agitation, the families often have to resort to chaining them, sometimes with fixed chains that patients wear for days or weeks, to deal with their crisis. When asked about these methods, the families clearly explain that they do not know how to handle the patients in moments of severe aggressiveness and agitation, when they pose a danger to those around them, so they apply these measures. Even If we empathize with the family’s need to control the symptoms, we have to take into account that these measures are extreme and in violation of basic human rights. This is one of the reasons why it is paramount to work on mental health awareness, so that when they face these types of symptoms families know where to turn to for professional help.

Lack of awareness and stigma are two sides of the same coin. Lack of awareness leads to stigma, discrimination, and segregation, and this leads to people hiding their conditions, increasing their suffering and isolation. This is particularly the case for women who are discouraged from sharing their feelings and from speaking up about their psychological struggles. In many cases this leads to severe states of depression.

Hafsa* holding her own hands during a chat with psychologist during a counselling session at mental health clinic supported by MSF at Al-Gamhouri Hospital in Hajjah. Yemen, 2021. © Nasir Ghafoor/MSF

What’s the way forward from here?

In our daily work at the Doctors Without Borders clinic in Hajjah, we try to normalize mental health issues and help change the social understandings and associations that link mental health conditions with things like “craziness” and “danger”. These associations create stigma and suffering for mental health patients and their families. Norms do not change as fast as we would like, but it is our hope that if we keep committing to our work, the changes in our practices will have a direct impact on the way these notions are articulated within society, leading to a slow but hopefully sustainable change.

Even if the conflict were to end tomorrow, what it has done to people’s psychological health will be seen and felt for many years to come. Yemen needs a long-term comprehensive approach including more services to address the looming mental health crisis. If overlooked, mental health issues can turn into chronic problems on a larger scale, resulting in the isolation of those suffering from disorders. This can lead to further damage to the social fabric, which is already very weak. It is our hope that through our collaborative work we can contribute to improving the mental health conditions of a population that has already had to face and overcome adversity at profoundly deep and devastating levels.