Mediterranean Sea: survivors seize the right to speak

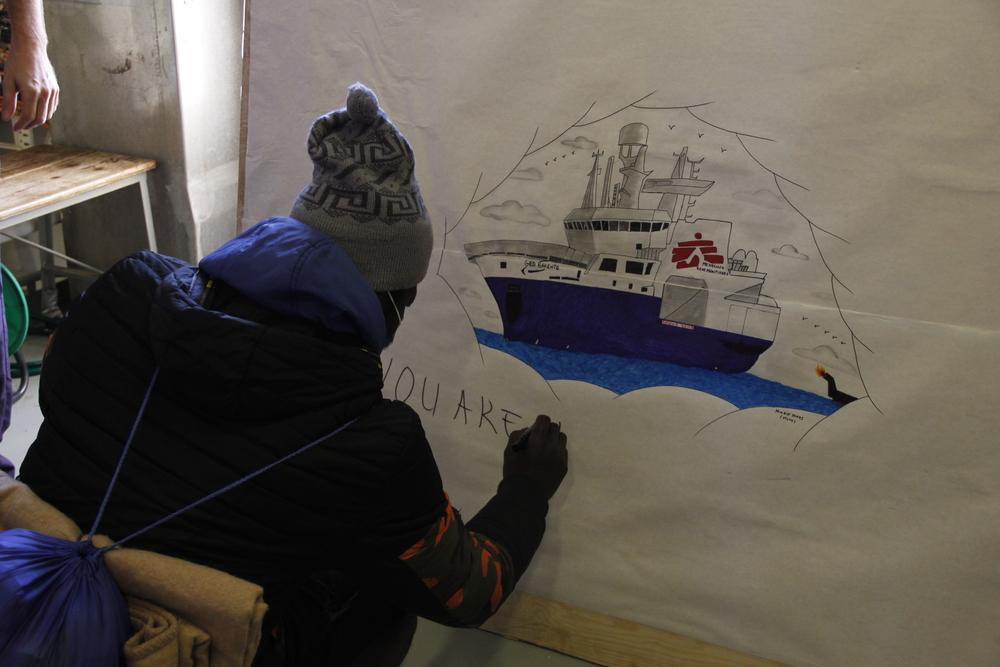

François (not the real name) from Cameroon is one of 558 survivors on the Geo Barents. He endured violence in Libya and survived the central Mediterranean Sea. He's been sharing his art with the our team to express his gratitude and raise awareness about the abuses people face. Mediterranean Sea, December 2021. © Eloise Liddy/MSF

In December 2021, the Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) search and rescue vessel Geo Barents saved 558 people across eight rescues of boats in distress in the Central Mediterranean.

Many of these people had not only survived the sea, but also severe violence—inflicted in Libya, from where they had fled; in their countries of origin; and during their journeys.

There were several people who arrived on board with physical injuries that were visibly fresh, including fractured bones. These types of injuries required urgent pain management, which can be challenging in the crowded environment of the ship.

Most told our medical teams that these injuries had been sustained just before or during the time they were leaving the Libyan coast. Others had older wounds. Some people said that their injuries were inflicted in Libya by detention centre guards and non-state armed groups, and others that it occurred at the hands of the Libyan Coast Guard during interceptions at sea.

“I suffered a lot in Libya,” says Aissatou (not the real name), a 21-year-old woman from Cameroon. “When I entered Libya, I didn’t have any scars. Now, my whole body is covered in scars.”

A Doctors Without Borders' midwife assisting a survivor from rescue 4, on December 22, 2021. Mediterranean Sea, December 2021. © Eloise Liddy/MSF

Aissatou has a large scar on her chest, a reminder of being stabbed as she escaped from a prison in Libya. “It was a women’s prison, so the guards were always raping the girls. They did not feed us well. We did not have clothes; we lived in the dirt. Whenever we tried to escape, they called the [gangs] to come and whip us… they beat us with their Kalashnikovs.”

One day, several of the women including Aissatou managed to run out of the prison. “When [the guards] saw that the girls were escaping, they took everything they could—iron [bars], weapons—to hit us. This is when a guard stabbed me in the chest. He stabbed me with a metal pipe,” she says. “Many girls were injured, but we ran anyway. My clothes were damp with blood. I asked people in the street to hide me.”

Another man speaks of the violence he experienced in Abu Issa detention centre in Zawiyah, roughly 50 km from Tripoli, where he was held for over a year. “They would beat us every morning… sometimes they hit you with their guns, [or] wooden or metal pipes; electricity; everything. I suffered from a lot of injuries.”

“People told us about being beaten or stabbed, with wooden or metal sticks,” says Doctors Without Borders medical team leader Stefanie Hofstetter. “Others reported being beaten with guns. We also saw people with smaller wounds all over their bodies: when we asked about these wounds, they usually said that they’d been burnt with hot water or melted plastic poured onto the skin.”

Hofstetter says that medical teams on search and rescue ships in the Central Mediterranean have been treating rescued people with these types of injuries for years.

Enduring horror in silence

Several survivors rescued by the Geo Barents in December 2021 disclosed experiencing or witnessing sexual violence—both in Libya and in their countries of origin—including transactional sex, forced prostitution, rape, forced marriage, trafficking and female genital mutilation. Many had experienced this abuse over a long period of time.

Aissatou was among those who experienced sexual violence while being held by traffickers in large warehouses near the sea, before entering the boats leaving Libya. “The smugglers, they rape us in the campo (warehouses). If you refuse, they will put the blade on you... you have no choice.”

Ahmed*, 17, from a Sub-Saharan African country, witnessed rape while in prison in Libya. “A lot of people suffer… for women it is hard. Libyan men will take a woman [from the prison]; she will come back sick, with no medical assistance.”

Ahmed says that in Libya, it was impossible for survivors to report these horrific experiences or ask for help for fear of retaliation: “If you speak, they kill you or [the woman].”

Aissatou agrees: “We suffered many things, but we did not speak [in Libya]. Who would we complain to? There is no law. You can only pray to God that if you go in the water, someone will save you.”

A Doctors Without Borders' psychologist on board the Geo Barents talking to a survivor. Mediterranean Sea, December 2021. © Eloise Liddy/MSF

The opportunity to speak

For survivors who have experienced long periods of fear and stress associated with severe violence, the Doctors Without Borders medical team on the Geo Barents focuses on basic mental health support that begins to provide a sense of safety and dignity.

Psychologist Hager Saadallah says the opportunity for survivors to speak with a medical professional and have their experiences acknowledged is often one of the most significant things the team can offer.

“What people need at this point, as they are still on the move, is to simply have the possibility to speak about what they have been through,” she says. “Being able to speak, and have someone listen, is completely normal for you or me. But it’s something survivors often haven’t had access to.”

Geo Barents midwife Kira Smith says this opportunity is especially important for those who have experienced sexual violence.

Often, when I speak with one of the survivors, it’s the first time they’re talking to anyone—especially a professional—about what happened to them. I aim to make them feel safe and valued, and to let them know that it’s not their fault. That sets the foundations for what they should expect and feel they deserve from care providers down the track. While there’s a lot we can’t do for people in their short time on the ship, they deserve to be heard and to be treated with dignity.Kira Smith, Midwife

Doctors Without Borders has been running search and rescue (SAR) activities in the Central Mediterranean since 2015, working on eight different SAR vessels (alone or in partnership with other NGOs). Our teams have saved more than 80,000 lives. Since launching search and rescue operations on board the Geo Barents in May 2021, Doctors Without Borders has rescued 1,903 people and recovered the bodies of 10 who died.

Between 17 and 24 December 2021, Doctors Without Borders teams on board the Geo Barents rescued 558 people from boats in distress in eight rescue operations in the Libyan and Maltese Search and Rescue Regions. Among the survivors, 35 were women, two of them pregnant, and 174 were minors, of whom 143 were unaccompanied.