Tales of Women at Sea

Miriam from Côte d'Ivoire is one of survivors on board of Geo Barents. Mediterranean Sea, December 2022. © Mahka Eslami

The experiences recounted by these four survivors are sadly common among the women and men rescued by the Geo Barents, the Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) rescue ship in the central Mediterranean. On the occasion of International Women's Day on 8 March, Tales of Women at Sea aims to amplify the voices of women rescued, as well as share stories from male survivors about important women in their lives. Through portraits and testimonies, the survivors describe the circumstances that led them to cross the central Mediterranean, the deadliest sea migration route in the world. Their stories are accompanied by testimonies from female Doctors Without Borders staff, who explain their motivations for the life-saving work of search and rescue, and the bonds felt with survivors on the Geo Barents.

Anyone crossing the sea to escape a dangerous situation or to find a better life is in a vulnerable position, but women face the additional burdens of gender discrimination and, all too often, gender-based violence, along their routes. Women represent only a small proportion - around five per cent - of those who make the dangerous journey from Libya to Italy.

On board the Geo Barents, female survivors regularly disclose practices such as forced marriage or genital mutilation (affecting either themselves or their daughters) as being among the reasons they were forced to leave their homes. Women also face specific risks during their journeys - Doctors Without Borders medical teams report that women are proportionally more likely to suffer fuel burns during the Mediterranean crossing, as they tend to be placed in the middle of the boat where it is thought to be safest. Many women rescued also report having experienced various forms of violence, including psychological and sexual violence and forced prostitution.

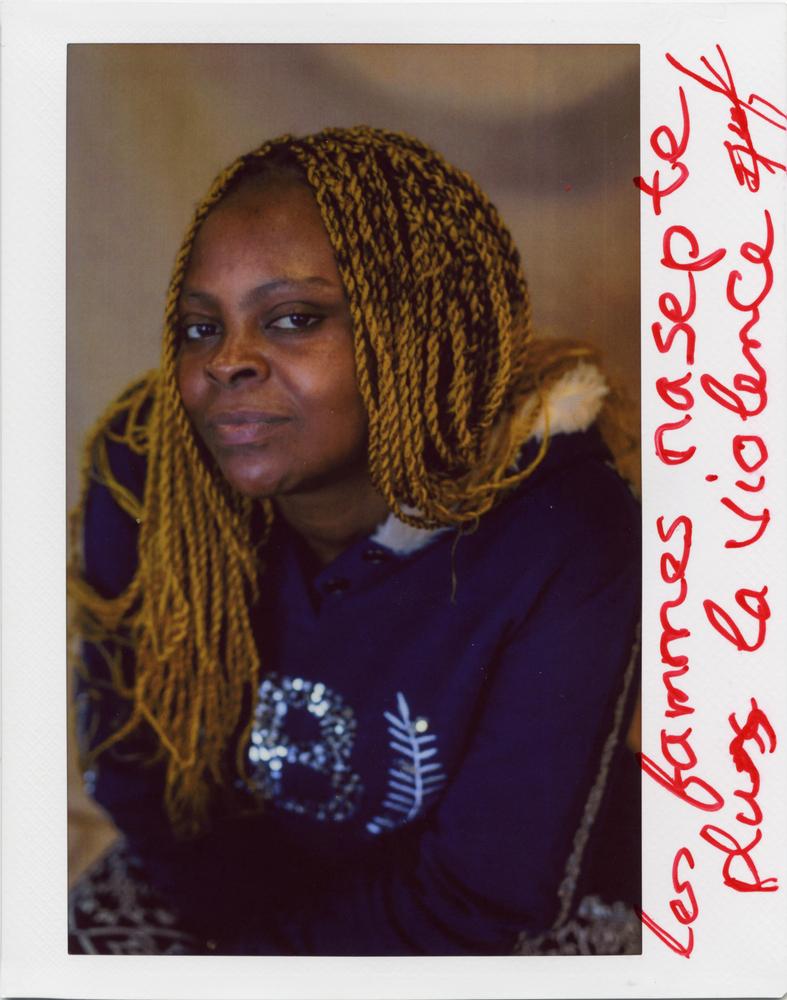

"Women, do not accept violence anymore!" Note from Decrichelle, a 32-year-old Cameroonian. Mediterranean Sea, 2022. © Mahka Eslami

Among these women is Decrichelle, who fled a forced marriage to a violent husband with her baby. They left their home country of Nigeria and went via Niger to Algeria. When they arrived in the desert, Decrichelle’s daughter fell ill and she could not do anything to treat her because she had no access to care or medicine. The young girl died, and Decrichelle had to leave her behind before continuing the journey to Algeria: “an immense and inconsolable sadness” for her.

Decrichelle attempted to cross the sea once but was arrested and sent to prison, where she was released immediately, only to be taken by taxi to a brothel. Some Cameroonian friends helped her escape. For six months, she lived in the campos (the abandoned buildings or large outdoor spaces near the sea where traffickers gather migrants) before scraping together the money to pay her way for another crossing.

Beyond the difficulties women face on migration routes and in Libya, Doctors Without Borders teams on board the Geo Barents often witness the strong bonds that develop between survivors on the women's deck. The women come together to support one another with daily tasks and childcare.

“I want to tell women: it is not your fault. You are exactly the same person as you were before. You are even stronger,” says Lucia, deputy project coordinator aboard the Geo Barents, who has herself experienced rape. “I think it has been really moving to see these women, who actually escaped what I experienced for an hour of my life, and in their struggle, their strength and their hope, [they do not stop] this fight,” she adds.

Deputy project coordinator Lucia speaks of her admiration for the courage and resilience she sees in survivors and how they inspire her to live her life despite her own trauma. Mediterranean Sea, January 2023. © Nyancho NwaNri

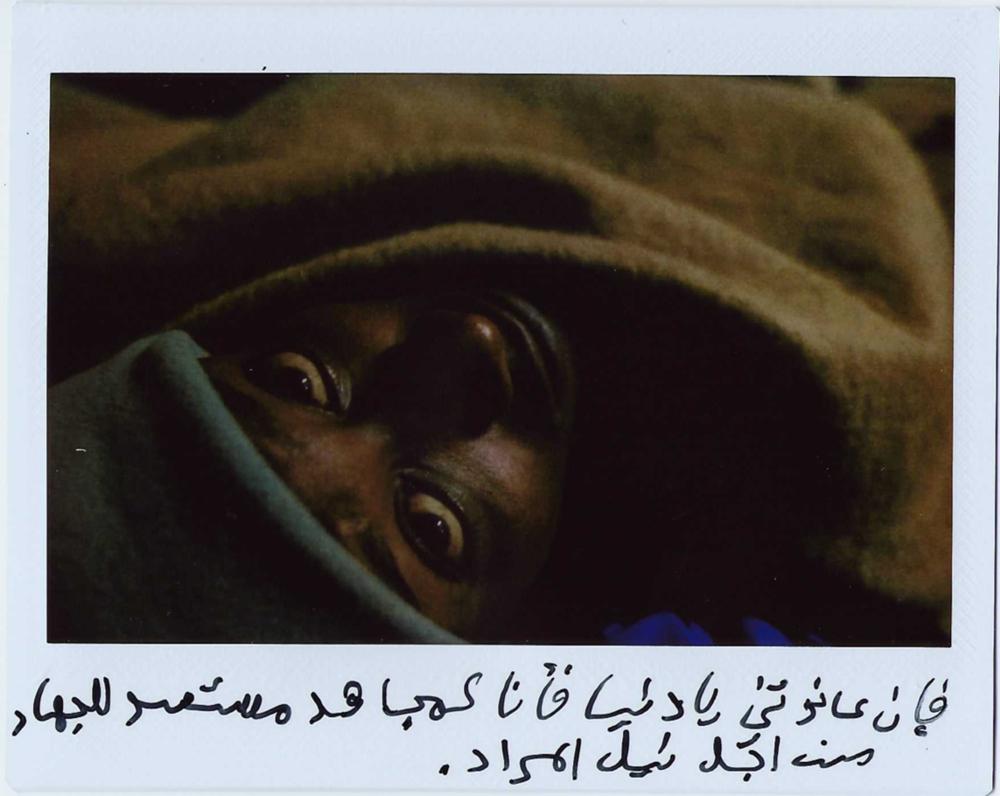

Meanwhile, when male survivors are asked about the people they left behind or the reasons for their journey, a woman is always mentioned in their stories. Ahmed, 28 years old, was born in Sudan to Eritrean parents who moved to Sudan to escape the war. Having lived all his life as a refugee, Ahmed never felt that he belonged in Sudan. He wished to leave, but as an undocumented person, unable to return to Eritrea for fear of military conscription and an oppressive dictatorial regime, he decided to travel to Libya and cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.

Ahmed’s mother was the only one who stood by him when he decided to convert from Christianity to Islam, despite harassment from his other family members.

"If you, life, has chosen to challenge me, I am the warrior ready to fight to achieve his goals." Note from Ahmed, a Sudan-born Eritrean rescued on Geo Barents. Mediterranean Sea, January 2023. © Nyancho NwaNri

“[Converting to Islam] affected me, affected my friendships… for sure [I faced issues because of that]. At first, from the family… in the beginning, I was secretive… until my family knew; then the harassment started. But my mother accepted me. She told me, ‘Whatever makes you comfortable, do it.’” Ahmed says his mother is one of the reason she was able to make the journey from Sudan through Egypt and into Libya. “She has a really big role in my life. She was continuously supportive and motivating me, wishing me the best. She is my inspiration… I hope to meet her again.”

Nejma, cultural mediator on board the Geo Barents, explains her bond with survivors like Decrichelle and Ahmed: “I am African and I am Middle Eastern. I am a mother. I am a woman. There are so many things that link us together. Maybe also the fact that I had to flee. That is a big part of it. I think it helps me understand where people are at the moment we find them; it is an understanding that books could never teach me.”

Cultural mediator Nejma talks with survivor Ekesili Emenike on the Geo Barents. In addition to bridging languages and cultures, Nejma, who was a refugee herself, spends time with the survivors both individually and collectively to answer their questions and provide them with much needed advice and support. Mediterranean Sea, January 2023. © Nyancho NwaNri

As a refugee herself, Nejma shares what helped her to move forward in the places she fled to. “[Survivors need to] keep the strength... once they disembark in Europe, it is not the end of the journey,” she says. “It is a different challenge: to not let go of who they are, to never forget who they are, where they are from. To be very proud of their origins. Because you will not know where to go if you do not know where you came from. And I want my brothers and sisters from Africa and the Middle East, or anywhere, to remember who they are. It will make it easier to move forward.”

Doctors Without Borders and search and rescue activities

Doctors Without Borders has been running search and rescue activities in the central Mediterranean since 2015, working on eight different search and rescue vessels, alone or in partnership with other NGOs. Since 2015, Doctors Without Borders teams have provided lifesaving assistance to more than 85,000 people in distress at sea. Doctors Without Borders relaunched search and rescue activities in the central Mediterranean in May 2021, chartering its own ship, the Geo Barents, to rescue people in distress, to provide emergency medical care to rescued people, and to amplify the voices of survivors of the world’s deadliest sea crossing. Since May 2021, the Doctors Without Borders team on board the Geo Barents has rescued 6,194 people, recovered the bodies of 11 people and assisted in the delivery of one baby.