Follow where your heart leads

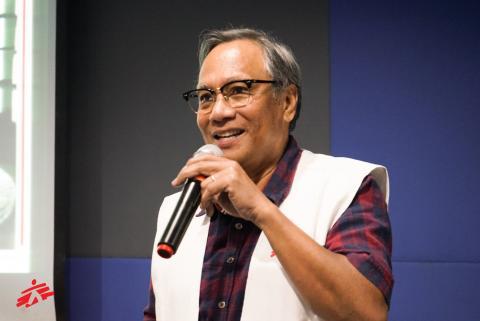

Dr. Francisco Raul Salvador is one of Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) seasoned field workers. He was in Marawi as the medical coordinator support of the Doctors Without Borders mission there. Doctors Without Borders has been in Marawi since October 2017, supporting the outpatient department and emergency room of a rural health unit.

February, the month of love and beating hearts, always makes me contemplate the pacemaker in my chest. I had it in 2013, two months before Supertyphoon “Yolanda”— the tragedy that made me decide to return to humanitarian work for good.

You see, I was born with a heart that leisurely beats: only an average of 55 a minute, short of five more beats to normalcy. It was not a problem until I turned (coincidentally) 55. I was back in the Philippines then from my first mission in India with Doctors Without Borders. While waiting for my next mission, I had taken a job as hospital administrator at the Metropolitan Medical Center.

I was in the hospital hallway one day when I experienced a blackout. The worst was when I was behind the wheel with my entire family along Edsa. We were lucky we got home that day.

The tests revealed that I had arrhythmia, or the irregular beating of the heart. I was at high risk of stroke; my heart was not working properly to ensure enough blood flow to the brain. Because of these, I agreed to a pacemaker implant in September 2013.

One of the inflatable hospitals Doctors Without Borders put up in Guiuan, Samar as part of its Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) response. Philippines, 2013. © Florian Lems/MSF

In just a little over two months of recovering, Yolanda happened. Due to the magnitude of the tragedy, I decided to put my newly equipped heart to the test.

I joined our hospital’s medical mission to Aklan on Nov. 26. When it ended, I returned to Manila with a heavy heart. I felt that I had to do more, being fortunate enough to be alive, thanks to the apparatus in my chest that makes sure my heart keeps going. I have resolved that, just like this pacemaker, those of us who were able to help must stand in the huge gap left by the disaster, to prevent further loss of lives.

I wanted to return to the Visayas, so I took a leave of absence from my job in the hospital. On Dec. 4, I once again joined Doctors Without Borders, onboard a chopper to a mission in Eastern Samar.

Every week, the Doctors Without Borders tented hospital in Eastern Samar admitted 60 to 70 patients, had 20 to 30 maternity admissions, and conducted an average of 10 surgeries. The outpatient clinic in the tented hospital had an average of 110 consultations per day. Aside from attending to patients, I traveled to various towns in the island as part of the assessment team making recommendations for the response mission.

The weather was not friendly, even for just a few hours of rest after an exhausting day. It was blistering hot in our sleeping tents, while outside was always cold and damp. I developed a viral cough, but I managed to finish my two-week support mission because I was highly motivated. The way I saw it, our troubles were nothing compared to the unimaginable loss suffered by the survivors.

Seeing people get help made my heart fulfilled. So I heeded its beating toward the direction of medical humanitarian work. In 2014, I went to South Sudan for Doctors Without Borders' malaria outbreak response mission. The situation was dire. Doctors Without Borders treated over 170,000 malaria patients that year, more than triple the number in 2013. In our mission in Gogrial, children with high-grade malaria fever were admitted on a daily basis. Convulsing children were particularly agonizing for me. We did our best with everything that we had.

That mission took a toll on my heart, metaphorically and literally. After six months, the pacemaker had to be repaired, because the battery power was depleted by 50 percent. That, however, didn’t stop me from going to conflict-torn Eastern Ukraine in 2015. This time, instead of the patients coming to us, we had to be the one to reach them.

The heavy fighting trapped many civilians, and medical facilities became constant targets of attacks. Most of our patients were ailing or injured elderly who volunteered to be left behind in their homes during the evacuations, convincing their families that they were too weak to run from the war and that they were going to die anyway. An elderly man told me that he did not want to burden his children and grandchildren. It was a poignant story for me to hear. But, it toughened my heart to withstand fear, focus on the mission, and make our patients feel that every beat of their hearts counted by providing quality healthcare.

That year, Doctors Without Borders teams carried out 159,900 basic healthcare consultations and 12,000 mental health consultations, in cooperation with Ukraine’s Ministry of Health.

That experience, I think, prepared me for another conflict area mission in Yemen the same year. And I’m glad I joined this mission, because it was where I experienced a most touching act of kindness. A woman was brought to our emergency room with severe abdominal pain. I was examining her when she suddenly kissed my hand. I asked a colleague what it meant, and I was told that such was an act of respect and gratitude. It moved me, because in overseas missions I’ve been to, self-expression is often a challenge given the language barrier and the oppressive physical pain our patients experience. It was heartening to encounter such kindness—a way beyond words to express gratitude.

Just last month, I visited my alma mater, the University of the East Memorial Medical Center College of Medicine, for a career talk, where I shared my story as an Doctors Without Borders field worker. Seeing some curious, interested faces made my heart flutter in ardent hope that they, too, would go where their heart takes them. Maybe, if we follow our heartbeats, we will find our purpose. And keeping other people’s hearts beating is, I believe, something worthwhile.

First published on the Philippine Daily Inquirer on 16 Feb 2019.