In 1971, a group of doctors and journalists founded Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders, with the aim of providing lifesaving assistance to the most vulnerable, regardless of gender, race, religion, creed or political affiliation; and the belief that medical needs outweigh respect for national boundaries.

Fifty years later, Doctors Without Borders continues upholding its principles of independence, neutrality and impartiality, while carrying out its humanitarian work despite challenging settings and limited resources.

We hope to be there for people who need us the most for the next 50 years .

Our Milestones

DOCTORS WITHOUT BORDERS FOUNDED

A group of French doctors and journalists creates Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in the wake of the war and accompanying famine in Biafra, Nigeria, and the floods in east Pakistan (now Bangladesh). © D.R

CAMBODIAN REFUGEES

Doctors Without Borders establishes its first large-scale medical program during a refugee crisis, providing medical care for waves of Cambodians seeking sanctuary. © MSF

IRAQ ATTACKS KURDS

Doctors Without Borders is the first medical organisation to bear witness to the use of chemical weapons on the Kurdish town of Halabja. © MSF

GENOCIDE IN RWANDA

Doctors Without Borders remains in Kigali throughout the genocide of more than 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus, and makes the unprecedented decision to call for international military intervention. © Rogerr Job

AWARDED NOBEL PEACE PRIZE

Doctors Without Borders is honoured for its ‘pioneering humanitarian work on several continents’. © Patrick Robert

TSUNAMI HITS SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Doctors Without Borders receives USD 133 million from the public and asks people to stop making donations for the crisis, having received more funding than is needed for its medical programmes in the region. Doctors Without Borders also asks donors if they consent to reallocating some of the funds received – to which the vast majority agree – to other Doctors Without Borders’s emergency medical programmes around the world. © Francesco Zizola/Noor

SUPER TYPHOON HAIYAN RESPONSES

Doctors Without Borders responds in the aftermath of super typhoon Haiyan, which caused an unprecedented disaster in the Philippines. Doctors Without Borders establishes inflatable hospitals, runs mobile clinics, and distributes more than 71,000 kits of basic supplies. © Agus Morales

EBOLA EPIDEMIC IN WEST AFRICA

At the peak of the largest Ebola outbreak in history, Doctors Without Borders employs nearly 4,000 national staff and over 325 international staff. Doctors Without Borders admits a total of 10,376 patient to its Ebola management centre. The outbreak ends in June 2016. © Anna Surinyah/MSF

ROHINGYA REFUGEE CRISIS

From 25 August, more than 655,000 Rohingya refugees flee Bangladesh following targeted violence against them in neighbouring Rakhine state, Myanmar. Most are living in dire conditions in the refugee camps. Doctors Without Borders expands its operations in the area, covering water, sanitation and medical activities. © Antonio Faccilongo

COVID-19 PANDEMIC

With nearly 85 million of people infected with COVID-19 and close to two million deaths, 2020 has become been a hard year for everyone, including Doctors Without Borders. We focus on continuing to provide care in our existing projects, while also opening new projects on COVID-19. © Abhinav Chatterjee/MSF

Make Your Impact

You can make an impact for people in need of medical assistance by joining us today with a monthly donation.

Your contribution ensures that we can send skilled medical professionals to provide medical care to people in urgent need.

- ACCESS

TYPHOON HAIYAN - 2013

When Typhoon Haiyan (or Yolanda, as it is known locally) ripped through the central Philippines on 8 November 2013, it caused a disaster of unprecedented scale . Whole communities were flattened, while a tsunami-like storm surge claimed thousands of lives. Roofs were blown off and livelihoods were swept away.

Challenges: Access to affected communities on outlying islands hard hit by typhoon

Following the disaster, many areas were inaccessible; bridges were destroyed, roads were impassable, power and communications were cut off, and fuel was in short supply. Partially damaged schools, stadiums and churches were turned into evacuation centres, where survivors crammed together waiting for help to come. Some 16 million people either lost their homes or livelihoods, and more than 6,200 people were killed.

The Visayas region was hardest hit by the typhoon. Encompassing Leyte, eastern Samar and Panay islands, it was—and still is--one of the poorest regions in the Philippines. This, combined with the sheer force of the wind and water, and the scattered geography of the archipelago, presented extreme challenges - first for the survival of the population and second for the delivery of relief.

Adaptation: Mobilising all means to assess the affected communities

In light of these tremendous efforts, Tacloban, one of the hardest hit areas, was the centre of rescue and relief operations and media attention. With scant information being received from outlying islands, Doctors Without Borders decided to split its teams to assess the needs in other areas.

Doctors Without Borders teams went to the provinces of eastern and southern Samar, northern Cebu, northern and southern Leyte, Panay, Negros Occidental and Palawan to assess the extent of the damage and the needs. These areas were particularly challenging to access, so Doctors Without Borders mobilised all possible means, including boats, trucks, chartered planes, commercial flights and helicopters.

Two mobile medical teams – one land-based, the other travelling by boat – ran mobile clinics to reach inland villages and outlying islands. These were particularly important because they made primary healthcare services and referrals for more advanced care available to people who were otherwise isolated or without access to medical services.

Within days of Typhoon Haiyan, Doctors Without Borders was able to provide emergency assistance to communities on three of the most affected islands: Guiuan and nearby towns on eastern Samar; Tacloban, Tanauan, Ormoc, Santa Fe and Burauen on Leyte; and Estancia, Carles and San Dionisio on mainland Panay, as well as several outlying islands. This included addressing acute and immediate medical trauma needs; restoring basic medical services and facilities; providing shelter, reconstruction kits, water and sanitation facilities; and offering psychosocial support to both children and adults.

SEARCH AND RESCUE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN - 2015

People from Asia and Africa crossing the sea and land borders into Europe without visas or permission has long been an issue. We saw the number reach its highest level in 2015, with more than 1 million arrivals.

Every year, thousands of people fleeing violence, insecurity, and privation at home attempt a treacherous journey via North Africa and across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. Countless lives are lost during the passage. Vast majority of people attempting the Mediterranean crossing pass through Libya, where they are exposed to horrific levels of violence, including kidnapping, torture and extortion.

Challenges: Countless lives lost while crossing the Mediterranean Sea

In different periods of the EU migration policy, people were either confined in camps on Greek & Italian islands waiting for refugee qualification or repatriation, or went on another border crossing journey all the way to countries more open to them.

Many attempts fail. People die at sea, or are caught and sent back by EU, and Turkish and Libyan coast guards.

Adaptation: Operate search and rescue vessels to save lives

In total, Doctors Without Borders teams took part in 682 search and rescue operations and assisted more than 81,000 people between 2015 and the end of August 2020. Basic medical and mental health services were also provided by Doctors Without Borders.

In late 2016, the SAR operations were accused of being a "pull factor" for migrants and refugees to attempt dangerous sea journeys and of "deteriorating maritime safety". Following severe security threats by the Libyan Coast Guards towards humanitarian NGO vessels, Doctors Without Borders partially suspended SAR activities in August 2017.

In view of these accusations, Doctors Without Borders and UK university researchers carried out an analysis of the available data on attempted sea crossings. It showed that the numbers of people attempting the crossing were not affected by rescue NGO's presence or absence but that coastguard activity against smugglers could increase the dangers to migrants. Rescue boats though did substantially decrease the number of deaths.

Since 2018, our SAR operations have encountered ever-larger obstacles. Our boat was stripped of its flag and registration by the Gibraltar and Panama Maritime Authorities, and then an Italian court applied to seize the boat because of what Doctors Without Borders believed were spurious claims of waste mismanagement.

Between December 2018 and July 2019, Doctors Without Borders had no SAR activities. We returned to sea in July but in September 2020 our boat was blocked from leaving port by Italian authorities. That detention lasted six months.

Doctors Without Borders returned to search and rescue activities in May 2021, saving the lives of people in distress trying to leave Libya, using our own chartered ship, the Geo Barents.

- EMERGENCY FUNDING

RESPONDING IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE INDIAN OCEAN TSUNAMI - 2004

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami had its epicentre off the west coast of northern Sumatra, Indonesia. It was an undersea megathrust earthquake with a massive reading of 9.1 on the Richter scale. The plate movements caused a series of huge tsunami waves that grew up to 30 m (100 ft.) high once heading inland. Communities along the surrounding coasts of the Indian Ocean were severely affected, and the tsunami killed an estimated 227,898 people in 14 countries.

Within 72 hours after the tsunami, the first Doctors Without Borders teams arrived in the affected areas. After initial assessments of needs, Doctors Without Borders decided to mainly focus its relief efforts on northern Sumatra and the southern, eastern, and northern coastal areas of Sri Lanka, where the catastrophe resulted in a huge number of deaths, as well as massive material destruction.

Challenge: A surge of aid money beyond the needs

What was unusual, or at least unprecedented, in this disaster was the quantity of media coverage. And that soon translated into a surge of aid money.

In Doctors Without Borders offices, like Hong Kong, New York and Paris, the fundraising departments were organised to respond very quickly to the needs of the operational medical teams. And they were delighted by the speed and generosity of people from around the world, people who wanted to do something about the horrors that they had seen reported from the scene.

As the teams on the ground became more aware of the extent of medical needs, and which ones Doctors Without Borders was best placed to meet, they now had an operational plan and a rough budget. It was immediately clear that Doctors Without Borders had more than enough money from emergency donations to cover the costs of what response teams should be doing.

Adaptation: Redirecting donation to other crises with donors' permission

After a week, Doctors Without Borders announced that it did not need any more money for this disaster. Doctors Without Borders sections received in total US$ 130 million, while the medical teams' forecast indicated that US$ 30 million would be sufficient to run programmes for the rest of 2005. Doctors Without Borders decided to contact its donors, asking their permission to derestrict their donations so that they could be used for other emergencies and forgotten crises. The response was overwhelmingly positive. Of all the people contacted, only 1% asked for their money to be refunded rather than redirected.

The reaction from the rest of the aid community and the news media was not universally positive. There were complaints that Doctors Without Borders's decision would damage the overall effort to fund the emergency response and that it was somehow disrespectful to philanthropic instincts.

That damage did not really demonstrate itself. Doctors Without Borders was always clear that there were huge needs for reconstruction and development that we were simply not qualified to meet, and which certainly deserved funding.

By the end of 2005, Doctors Without Borders had used over US$ 29 million of the donations to fund its operations in the Tsunami region and US$ 78 million to meet urgent needs in other emergencies and forgotten crises such as the nutritional crisis in Niger, the conflict in Darfur and the earthquake in Pakistan.

- FIELD STAFFING

COVID-19 PANDEMIC - 2020

A year on and counting, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to ravage countries worldwide. Many are still experience supply issues of specific medical equipment to save patients' lives and keep frontline healthcare workers safe.

In most of the countries where Doctors Without Borders is responding, access to vaccines has been a major problem. In Palestine, only two percent of the population had been vaccinated by March 2021, and hospitals have struggled to cope.

In Yemen, all aspects of the COVID-19 response are lacking and in need of greater international support, from public health messaging, to vaccinations, to oxygen therapy. India, which rode the first wave of COVID-19 relatively well, was overwhelmed by the second wave, which saw hundreds of thousands of people struggling to breathe, many dying without having received any medical care.

Challenge: Staffing and supply chain disrupted by COVID-19

Lockdown measures, travel restrictions, and a largely disrupted global transportation network posed major challenges to coordinating, staffing, and supplying Doctors Without Borders global COVID-19 response in 2020. Where international travel was possible, medical and project staff departing for or returning from international missions faced extra layovers, long travel times, and lengthy testing and quarantine measures.

Global stockouts and shortages of essential protective and medical equipment, severely disrupted transportation networks, as well as temporary import and export restrictions on items needed for the COVID-19 response posed extraordinary supply and logistical challenges.

Adaptation: Adapting to a new mode of care delivery

Despite these limitations, Doctors Without Borders continues to respond swiftly to the growing demands in many of our projects. With most commercial flights suspended for long periods, Doctors Without Borders staff relied largely on humanitarian charter flights to reach projects around the world. About 4,000 international staff travelled to Doctors Without Borders projects between April and December, only about 25% less than during the same period in 2019.

In some areas, our projects have been weakened, or we were forced to suspend our activities due to factors such as travel restrictions. Our locally-recruited staff, representing 90% of our employees in the field in our countries of intervention, have helped sustain our activities. We have also been able to adapt and innovate how we deliver care to maintain essential healthcare in our existing programmes amid this pandemic while accompanying ministries of health in preparing for or facing the pandemic.

From late February to the end of the year, Doctors Without Borders supply centres packed close to 125 million items for the global COVID-19 response, including personal protective equipment, medical devices, medication, testing material, and specialised laboratory equipment, with another 162 million dispatched for regular and emergency projects.

WEST AFRICA EBOLA OUTBREAK - 2014

The severity of the West Africa Ebola epidemic saw Doctors Without Borders launch one of the largest emergency operations in its history.

Between March 2014 and December 2015, Doctors Without Borders responded in the three most affected countries - Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone – and also to the spread of cases to other countries affected by Ebola. Doctors Without Borders employed around 5,300 national staff and international staff who ran Ebola management centres as well as conducted surveillance, contact tracing, health promotion and provided psychological support. Doctors Without Borders admitted 10,310 patients to its Ebola management centres of which 5,201 were confirmed Ebola cases, representing 1/3 of all WHO-confirmed cases. During the first five months of the epidemic, Doctors Without Borders handled more than 85% of all hospitalised cases in the affected countries.

Challenge: Field staffing and emergency fund

The duration of frontline field assignments during this Ebola outbreak was much shorter than usual – at the height of the outbreak, assignments for international staff would last a maximum of six weeks. This was to ensure that staff remained alert and did not become too exhausted and then infected. This high turnover resulted in huge HR needs. Also, we had to draw on a small pool of field workers with highly specific skill sets required in an Ebola setting, especially at the beginning of the response. The few foreign governments that were willing to support mainly focused on funding or infrastructure but not staffing.

Given the huge challenge in staffing, nearly one-third of the emergency fund in the first year of the response was spent on staff costs, due to the huge HR needs in such a large response.

When the outbreak became out of control and spilled out of the continent, people began to be much more aware and pour in financial resources to support. In October 2014, Doctors Without Borders decided to launch a dedicated, earmarked fund for Ebola.

Adaptation: HR Flexibility and Innovation

One of the ways to answer the problem was to try and mobilise even larger numbers of experienced international staff. The high levels of media interest in the Ebola crisis, Doctors Without Borders's response, and a strong dynamic in Doctors Without Borders's social networks, reinforced the global calls for more of those volunteers.

During the Ebola response, all other Doctors Without Borders programmes had to maintain their activities with fewer resources and support. With a very high level of unfilled positions, a new mobility policy was a concrete solution to decrease the pressure on HR.

More than 55 people relocated from their existing missions to the Ebola response. International positions were replaced by national staff, where they had the right experience and qualifications or where they could be reinforced through coaching and training.

Doctors Without Borders also decided to take the unusual step of training a large number of staff from other organisations. Because Doctors Without Borders was a leader in dealing with Ebola, we were able to transfer our knowledge to others. Doctors Without Borders also assisted WHO and the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) in developing their own training modules.

- LOGISTICS

PAKISTAN EARTHQUAKE - 2005

On Saturday 8 October 2005, an earthquake measuring 7.6 on the Richter scale, one of the biggest in recent years in this region, hit Pakistan, North India and Afghanistan. More than 150 aftershocks added yet more landslides. By December, over 73,000 were estimated to have been killed, 128,000 injured and over 2.8 million displaced in Pakistan.

Challenge: A large number of injured people in mountainous area inaccessible to health services

The mountainous terrain in that part of Pakistan means that some areas were all but inaccessible, making delivery of aid and even assessment of the needs difficult. The situation was made worse by roads blocked by landslides. We had to set up assistance in remote areas that are accessible essentially only by helicopter, or walked to get to our patients in remote locations where road access was blocked. Doctors Without Borders provided care to a large number of seriously injured people, and see to the material needs of those affected.

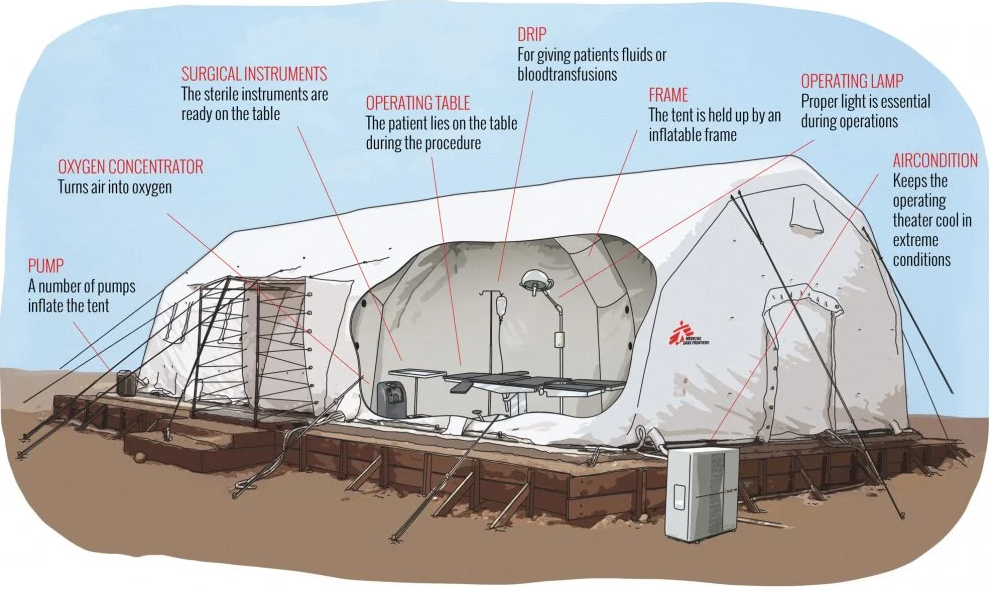

Doctors Without Borders deployed a surgical team and one of the inflatable hospitals to Mansehra, Pakistan, to help improve the quality of care there. The temporary hospital measured over 1000 m² with a 120-bed capacity, built under nine inflatable tents. This structure, which included four operating suites, an emergency room, and an intensive care unit, was put up in two weeks. This was the first time Doctors Without Borders was able to establish a substantial surgical presence following an earthquake. Around 700 injured received care in this temporary hospital in Pakistan.

Too often after a man-made or natural disaster, essential health structures including hospitals are completely destroyed. While some injuries can be treated in open air or temporary clinics that Doctors Without Borders often put up in these circumstances, significant numbers of patients will require surgery that can only be effectively performed in a closed and sterile environment.

Construction or even refurbishment of damaged health structures with operating theatres that meet the stringent medical requirements take far too long.

Adaptation: Inflatable field hospital to provide surgery and post-operative treatment

In 2004, when Doctors Without Borders teams saw the Italian Army using inflatable tents during the response to the tsunami in Southeast Asia, we immediately recognized their potential for us. We adapted the design, and began equipping our teams with state-of-the-art inflatable field hospitals—dramatically reducing the time it takes to begin providing trauma surgery and post-operative treatment.

Doctors Without Borders developed a 120-bed inflatable field hospital with a self-contained heating, sanitation, and water-purification system. This hospital can be quickly deployed around the world.

Advantages:

- Fast to install – 24-48 hours from delivery to receiving first patients

- Easy to disinfect

- Delivered as a kit. Surgical equipment and other materials already included to start initial service.

- Adaptable- can be set up as operating theatres, in-patient wards, pharmacy.

- Reusable (can be packed and re-deployed in another location)

Challenges:

- A lot of manpower is needed for the initial placement and set-up

- Temperature control is a challenge in hot climates

- SPEAKING OUT

ROHINGYA CRISIS - 2017

Following a concerted campaign of extreme violence by the Myanmar authorities against Rohingya people in Myanmar’s Rakhine state in August 2017, over 700,000 Rohingya fled over the border into the Cox's Bazar district of Bangladesh.

Prior to the influx of refugees in August, Doctors Without Borders were already offering comprehensive basic and emergency healthcare for Rohingya in Cox's Bazar. With the new arrivals, we have significantly scaled up our efforts in support of the growing population. We now manage multiple health posts, primary health centres and inpatient facilities across the camps.

How did the Rohingya crisis start?

The Rohingya are a stateless ethnic group. Majority of them are Muslim, and they have lived for centuries in the majority Buddhist Myanmar. However, Myanmar authorities contest this. They claim the Rohingya are Bengali immigrants who came to Myanmar in the 20th century. Prior to the military crackdown in August 2017, roughly 1.1 million Rohingya people lived in the Southeast Asian country.

Described by the United Nations in 2013 as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world, the Rohingya are denied citizenship under Myanmar law. Due to ongoing violence and persecution, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled to neighbouring countries, either by land or by boat, over the course of many decades.

Challenge: The largest refugee camp in the world

Refugees arriving in Bangladesh are often in dire need of medical care, having had no access in Myanmar. Finding shelter in the overcrowded camps is a challenge for the new arrivals. The exponential growth of the population in such a short amount of time has resulted in a severe deterioration of living conditions.

The situation is extremely precarious, with many people lacking access to healthcare, safe drinking water, latrines and food. What we see remains an acute emergency situation with huge humanitarian needs. Living conditions must greatly improve - with a focus on water, sanitation and shelter - to avert a public health emergency.

Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases among the refugees in Bangladesh demonstrate just how little access the Rohingya population had to routine healthcare in Myanmar. In the current context of the dense population, and poor water and sanitation conditions, the risk of people falling ill is high.

Cholera, diphtheria and measles vaccination campaigns have been carried out but risks of disease outbreaks remain.

Adaptation: Scaling up efforts to serve the most vulnerable with limited resources

Doctors Without Borders teams carried out more than 1.3 million medical consultations from August 2017 to June 2019, and continue to treat tens of thousands of patients a month. The most common conditions treated were respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and skin diseases—all related to poor living conditions. Teams have also worked to improve water and sanitation services, constructing more sustainable latrines, drilling boreholes, and tube wells, and installing a gravity-fed water supply system, making 193 million litres of chlorinated water available to 77,430 people.

The Rohingya had very limited access to health care in Myanmar, and the majority did not receive routine vaccinations. This makes them highly vulnerable to preventable diseases. Vaccination campaigns, supported by Doctors Without Borders,have been instrumental in preventing outbreaks of cholera and measles, and in containing the spread of diphtheria—a rare disease long forgotten in most parts of the world. In December 2017, Doctors Without Borders warned that diphtheria was re-emerging among the Rohingya. Diphtheria is a contagious bacterial infection known to cause airway obstruction and damage to the heart and nervous system, and can be fatal if left untreated. Doctors Without Borders treated more than 7,032 people for diphtheria in Cox’s Bazar district by the end of June 2018.

Teams provide medical and mental health care to the victims of violence, including sexual violence. Doctors Without Borders is working with other organizations to respond to the additional needs of pregnant survivors of sexual violence and children born as a result of rape. Women and children in the refugee camps are also particularly vulnerable to abuse and exploitation, and have been targeted by human traffickers. A Doctors Without Borders hotline is available for survivors of sexual violence to receive information about how to reach our services as soon as possible.

ACCESS CAMPAIGN - 1999

When your work involves lifesaving medical action, what do you do when the medicine your patients need is unavailable, expensive or toxic? While Doctors Without Borders is focused on humanitarian medical aid, the Access Campaign makes sure the right medicine is available to the patients who need it most.

Challenge: Scale of the problem

In the 1990s, treatment for HIV/AIDS included new, effective drugs called antiretrovirals. But in developing countries, pharmaceutical companies charged high prices for antiretrovirals, keeping them out of reach of most people living with the virus. The number of AIDS deaths in these countries kept rising. Many of them were places where Doctors Without Borders worked.

When patients and healthcare advocates worked together and generated political pressure, the price of HIV medicines dropped dramatically, allowing millions to receive life-saving treatment.

The same problem exists with other diseases that persist in many places where Doctors Without Borders treats patients, from tuberculosis and sleeping sickness, to malaria and drug-resistant infections, and patients do not have access to vaccines.

Adaptation: A solution that is an ongoing campaign

The Access Campaign was started in 1999 and it works to help people from to get the treatment they need to stay alive and healthy. This goes beyond life-saving drugs and includes tests and vaccines that are available, affordable, suited to the patients' needs, and adapted to the places where they live.

The vital missing link is to align drug development more closely with patient needs. What's necessary are medical tools that are more affordable, innovative, and effective in the places where we work.

In 1999, Doctors Without Borders was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. With the proceeds, the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) was established. DNDi is a collaborative, patient-centred, non-profit organisation. DNDi is proving that change and creative thinking in medical research and development can be an effective catalyst for new approaches to patient-centred drug development and access.

Since its inception, DNDi has already delivered seven new treatments for malaria, sleeping sickness, Chagas disease and paediatric HIV/TB coinfection, among other diseases.

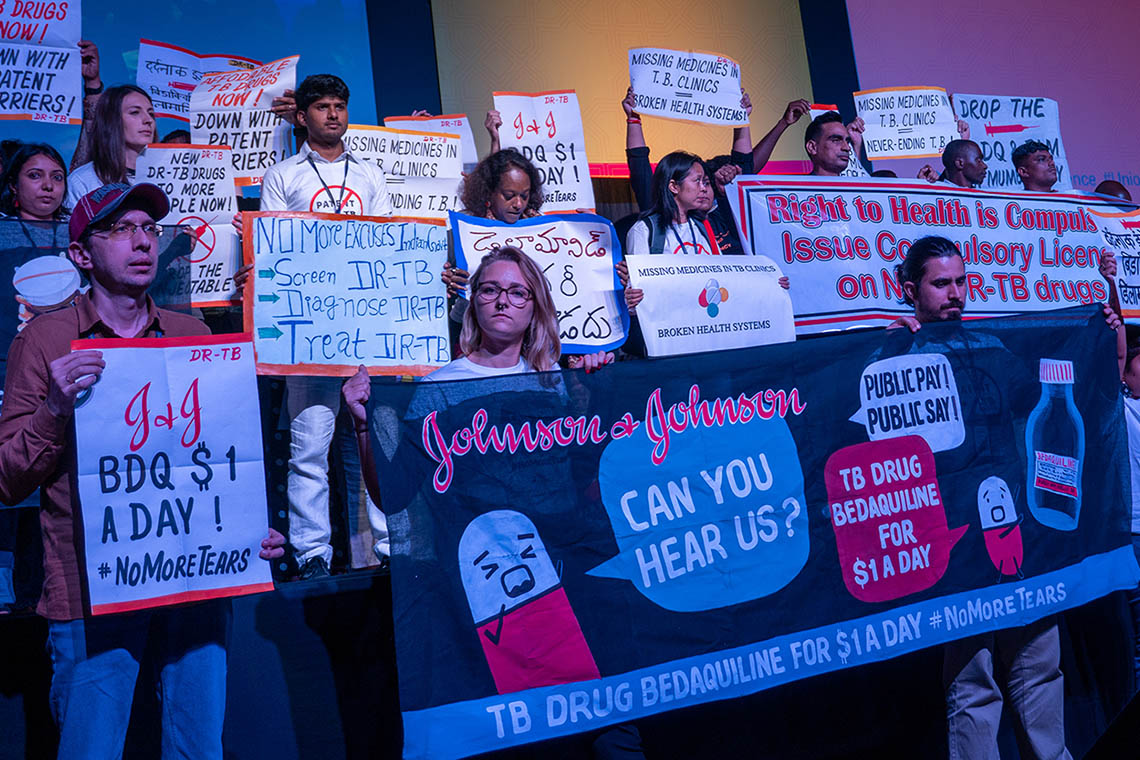

Tuberculosis treatment and trials

One of the diseases that Access Campaign has worked hard to treat is tuberculosis (TB). In 2019, TB remains as the world's deadliest infectious disease.

However, many people are unable to get tested, and the ones who do get diagnosed are often unable to get or complete the treatment they need. Cost is a significant factor, but so are the toxic side effects.

In 2012, the oral drug bedaquiline came to market. It was developed by pharmaceutical corporation Johnson & Johnson (J&J). WHO recommended bedaquiline as the backbone of DR-TB treatment, to replace older, more toxic drugs. But it cost too much for most patients.

For many years, Access Campaign pressured J&J to lower the price. Finally, in 2020, J&J announced a reduced price of US$1.50 per day.

But lower prices are just one part of the solution. Shorter, more effective treatment regimens are another.

In 2017, Doctors Without Borders,in partnership with many other health research organizations, pioneered new a clinical trial aiming to find a radically improved course of treatment for DR-TB. In January 2017, TB-PRACTECAL was born.

In March 2021, TB-PRACTECAL stopped enrolling patients. Its independent data safety and monitoring board indicated that the regimen being studied was superior to current care, and more patient data was extremely unlikely to change the trial's outcome.

Vaccine inequality in the pandemic

In 2020, everything changed when COVID-19 took over the world.

One year and over 150 million cases later, the world sees some hope, as vaccines are approved for use and vaccinations are taking place across populations. But as with many other diseases, access to vaccines, testing and treatment varies greatly in each country.

Over many months, the Access Campaign has asked governments to prepare to suspend and override patents and take other measures, to ensure availability and reduce prices to save more lives; and to work in solidarity to meet not only their domestic needs but also to support other countries to get access to effective medicines, diagnostics, and vaccines.

In October 2020, at the World Trade Organization (WTO), India and South Africa put forward the landmark ‘TRIPS waiver' proposal. As of April 2021, the proposal is officially backed by 59 sponsoring governments, with around 100 countries supporting overall.

With COVID-19, as with many other diseases, the work of the Access Campaign continues.

ATTACKS ON HEALTH FACILITIES - 2005

In war-torn countries such as Syria, Yemen, South Sudan and many others, health facilities have been attacked, looted and destroyed. Attacks against medical facilities and health workers, deprive people of health services, often when they need them the most.

Challenge: Staff killed in attacks at medical facilities

Since 2005, Doctors Without Borders has lost 23 staff in nine separate events, including during the storming or bombing of hospitals. There have been more than 350 incidents involving Doctors Without Borders health facilities, ambulances, and the communities we serve in Afghanistan, South Sudan and other countries.

Adaptation: Doctors Without Borders advocacy response and UN Resolution 2286

UN Security Council (UNSC) passed the Resolution 2286 in May 2016.

Doctors Without Borders worked hard to ensure that the provision of medical care on both sides of the front line is protected. The resolution was an attempt to reassert the legitimacy and protected status of humanitarian medical action.

The resolution also enhanced the protection of healthcare in conflict. It formally extended protection under International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to humanitarian and medical personnel exclusively engaged in medical duties. This includes staff, medical activities and facilities of private humanitarian organisations, such as Doctors Without Borders. It also clarified and solidified the protection of hospitals.

The problem remains

Five years since UN Resolution 2286 was passed, hospitals and medical and humanitarian workers continue to be threatened and targeted in conflict.

In 2020, there were eight reports of incidents in Doctors Without Borders projects. In Afghanistan, armed groups brutally attacked the Doctors Without Borders maternity wing in Dasht-e-Barchi hospital. In Syria, hospitals and clinics we support have been routinely bombed. Ambulances in war-torn Yemen often come under attack. Armed incursions into our health facilities have occurred in places including Sudan. This year, Doctors Without Borders has recorded six incidents already in just the first quarter.

Doctors Without Borders still demands answers

With the COVID-19 pandemic still raging, attacks on healthcare continue. We continue to employ mechanisms, such as ensuring we're clearly identified and that groups know who and where we are. In places like Yemen and Afghanistan, our logo is very clearly marked on our ambulances and on the roof of our hospitals, and we proactively share the coordinates of our medical structures. These negotiations and mechanisms require constant maintenance and vigilance through dialogue with parties to the conflict.

It's crucial for us and the work we do that we preserve the sanctity and protection of medical care, and that we have access to all parties in a conflict to secure that protection. Establishing these ‘deconfliction' arrangements – which then must be respected by all sides – is vital to prevent attacks.

But we cannot do it alone. States must take all the necessary steps to ensure the maximum protection for the wounded and the sick, and medical and humanitarian personnel.

In the wake of an attack where the army or a state armed group was involved, an independent and impartial fact-finding investigation can often be an effective way to bring accountability and help put in place measures to avoid it happening again.

Three years after the 2016 bombing of the Doctors Without Borders-supported Shiara Hospital in northern Yemen, the UK and US-supported Joint Incidents Assessment Team – which was appointed by the Saudi and Emirati-led Coalition engaged in Yemen – failed to provide any true accountability.

Following incidents like these, Doctors Without Borders conducts our own internal review and assessment of the event, often making our own findings public. But sometimes – regardless of whether the circumstances were clear or not – we decide it's simply too dangerous for our patients, our staff, or both, to continue working where there has been an attack. On a number of occasions, this has led to the extremely difficult and heart-breaking decision to withdraw – the consequences of which often means people are left without adequate access to healthcare.

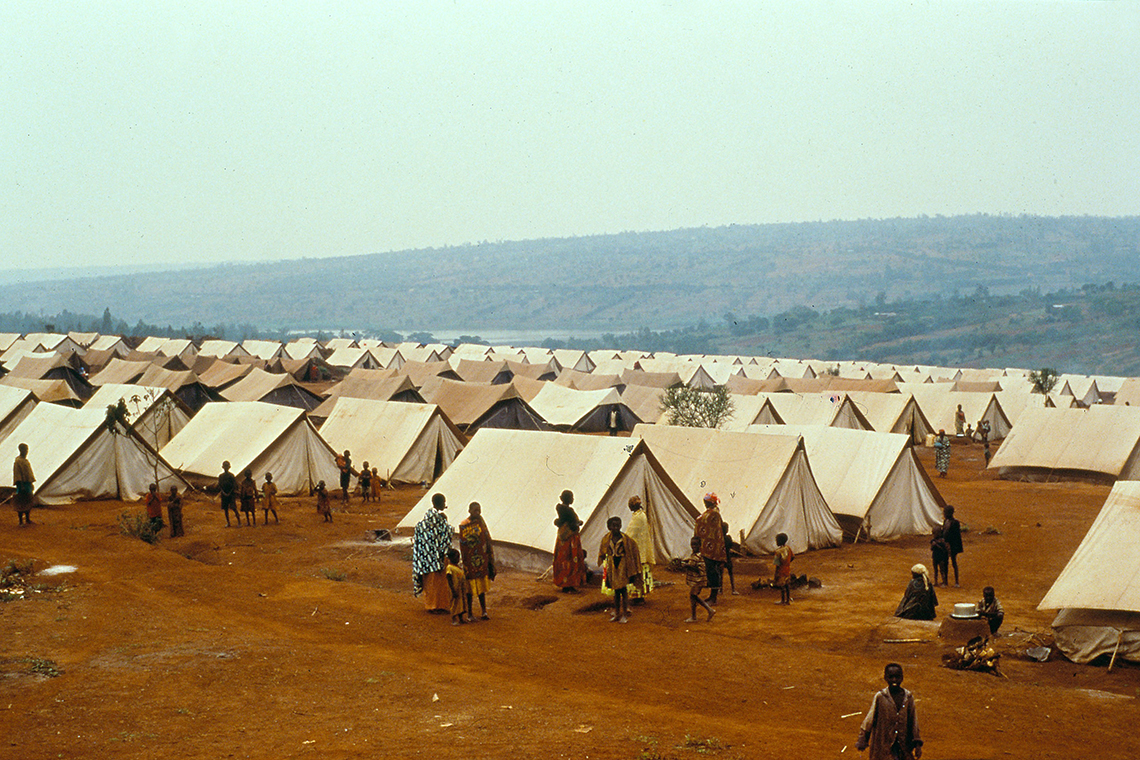

RWANDA GENOCIDE - 1994

For many years, there had been tensions between the Hutu and the Tutsi peoples of Rwanda. Though the Hutu settled in the country many centuries ago, the Tutsi minority ruled from the 16th century until the arrival of the Europeans in the 19th century.

In 1961, Rwanda declared itself a republic, and an all-Hutu provisional government came to power. Thousands of Tutsi began fleeing Rwanda.

Then from 1987, a predominantly Tutsi rebel organisation had been leading a war of re-conquest. In 1990, they first invaded Rwanda from the north, then a ceasefire was negotiated in early 1991, and negotiations between them and the government began in 1992.

On 6 April 1994, the plane carrying the Rwandan President was shot down as it approached the capital, Kigali. The slaughter — primarily of the Tutsi minority — commenced in the days that followed.

From April to July 1994, between 500,000 and one million Rwandan Tutsi were systematically exterminated by organized Hutu militiamen. The genocide was the outcome of long-standing plans by Hutu extremists. The extremists also killed many Rwandan Hutu who opposed the massacres and they seized power in Kigali in early July.

Challenge: Challenges beyond medical

From the moment these forces took control, Doctors Without Borders teams witnessed abuses and brutalities committed by the administration and the armed forces, particularly against displaced populations and detainees crammed into prisons. The violence increased in the months that followed, and rumours about the brutal behaviour of the new regime were corroborated by reports produced by human rights organisations.

When Doctors Without Borders teams attempted to help their neighbours in nearby houses, militiamen threatened them and ordered Tutsis to hand themselves in. In one such incident in Murambi, a town about 20 kilometres from Kigali, militiamen armed with clubs and machetes murdered a man right in front of several Doctors Without Borders volunteers.

On 13 April 1994, Dr. Jean-Hervé Bradol, the Doctors Without Borders programme manager for Rwanda and Burundi, arrived in Kigali with his emergency team to open a surgical programme and treat survivors.

"On 14 April, Rwandan Red Cross colleagues saw militia fighters take wounded patients out of ambulances and kill them on the side of the road."Bradol had what seemed to be an impossible task in such circumstances: to triage the wounded. "I examined each wounded patient and tried to determine whether it was worth the risk of travelling through part of the city and crossing all the militias' barricades. We treated less serious wounds on site, knowing that medical care was less critical to those patients than avoiding militia fighters who were planning to kill them."

Bradol estimates at least 200 Rwandan colleagues were killed during the genocide. "We don't know the exact number. Our offices were looted and our personnel lists were destroyed so it was impossible to get a precise count."

Adaptation: Speak out to criticise the inhuman condition

In April 1995, a Doctors Without Borders team witnessed the Rwandan army's deliberate massacre of over 4,000 displaced people in the Kibeho camp in southwest Rwanda. Doctors Without Borders spoke out publicly to denounce the killing and produced a report based on the eyewitness accounts of its volunteers.

The report documented the extent of the massacre, and differed greatly from the dismissive account prepared by an international commission of enquiry into what had occurred.

Doctors Without Borders again spoke out publicly in July 1995, to criticise the inhuman conditions in which detainees in Gitarama prison were being held and to call for improvements. This stance was backed by medical data collected by Doctors Without Borders volunteers.

In December 1995, the French section of Doctors Without Borders was expelled from Rwanda. The whole Doctors Without Borders movement regarded this move as a settling of scores by the Rwandan Government, given that it was volunteers of the French section that had directly witnessed events at Kibeho and had initiated the public denunciations.

At the end of 2007, Doctors Without Borders ended its 25 years activities in the country. The work had included assistance to displaced persons, war surgery, programmes for unaccompanied children and street children, responding to epidemics and so on.

- INNOVATION

CAMBODIAN REFUGEE CRISIS - 1976

In 1976, Doctors Without Borders established its first large-scale medical programme during a refugee crisis, providing medical care for waves of Cambodians seeking sanctuary. At that age, the idea of "humanitarian aid" was still relatively new. Doctors Without Borders teams in Thailand had no experience in refugee settings and no guidelines.

Challenge: Management of drugs and supply

Dealing with large number of refugees in Thailand was a new challenge to Doctors Without Borders,a rather young organization at that time. The field teams consisted of just doctors and nurses, with a high turnover, most of whom had no experience with the tropical diseases they had to learn how to treat.

Jacques Pinel, a pharmacist, joining the Doctors Without Borders project in Thailand in 1979 and described Doctors Without Borders as an "organization without organization. "One example was that drugs from different donor countries were in boxes piled under a tarpaulin and field workers took whatever medicines were easiest to find.

Innovation: Develop pre-packed emergency kits for various situations

Based on the work in Thailand, Doctors Without Borders learnt another lesson which is still valid today - the need to develop emergency kits that are adapted to each specific situation. Jacques Pinel created the first emergency kit in a kind of wooden cabinet, with all drugs and medical supplies perfectly displayed in what looked like little drawers. However, when he had finished the work, he and the team realised that the wood used to build it was far too heavy and could only be carried in the back of a pick-up truck. Hence the nickname, "semi-mobile equipment."

In the refugee camps Doctors Without Borders served, there were women ready to give birth, patients who had injuries, respiratory infections, and malaria that needed care. Several standard toolkits, including the "semi-mobile equipment", were made.

They were large boxes made by local carpenters that could serve as an examination table and that contained emergency kits and drawers in which supplies were classified by need. Standardized drug and equipment lists, including user manuals, were packed into kits.

Since then, Doctors Without Borders Logistics has created many others. The vaccination kits for measles, meningitis, and yellow fever enable Doctors Without Borders quickly to set up a cold chain and they include all medical and logistic supplies necessary for a vaccination campaign by several teams of vaccinators. There is also a kit for creating a hospital with inflatable tents within 48 hours, which has been used to treat patients in the aftermath of natural disasters in countries like Haiti, Philippines and Nepal, and in conflict zones of Yemen and Syria.

DECENTRALISED CARE - HIV TREATMENT - 1976

Significant advances having been made in HIV treatment over the last 25-30 years, including the efficacy and affordability of anti-retroviral therapy. Though the cost of first-line drugs is now cheaper than ever, but more than 12.6 million people were still missing out on receiving treatment at the end of 2019. While 1.7 million people became newly infected with the virus in 2019. Amongst 38 million people living with HIV/AIDS, over two-thirds of them live in sub-Saharan Africa.

Challenges: Huge needs but very few resources to manage a chronic disease in poor countries

The reality of the HIV pandemic is that the largest public health effort that humanity has ever undertaken to manage a chronic disease is fought primarily in poor countries. There are huge needs but very few resources in these countries. They cannot cope with a continuous flow of patients who require life-long follow up and treatment.

Stable patients want to live a normal life, without having to frequently come to overcrowded hospitals and queue for hours just to pick up their medication. In most circumstances, the time on the journey and in the hospital means they will lose a day's pay, which means lost food for themselves and their family.

In long running conflict areas like South Sudan and the Central African Republic, people will face a deadly cocktail of obstacles to access medical facilities for their treatment. Many people living with HIV have to make long and often dangerous journeys to find a clinic that offers HIV testing and care. Those who reach them, sometimes find empty shelves instead of the much-needed drugs, making it impossible for them to continue their ARV treatment.

Adaptation: Decentralise treatment with patient at the centre of care

Over the years, Doctors Without Borders has piloted and developed ways of decentralising treatment with a patient-centred and community-focused approach.

The decentralised care separates different kinds of appointments. Since the needs of different patients are different: there are those to see a doctor or nurse for a check-up, which is only necessary once a year for patients whose HIV treatment is monitored by viral load count. And there is picking up a supply of daily ARV drugs, which can be as frequent as once every month. The delivery of drugs is organised at community level through the support of peer groups.

A patient-centred approach could mean:

- Adapting clinic opening hours to suit the patients. They might be early morning clinics, so people can drop by on their way to work or late-night clinics for commercial sex workers;

- Letting people have three or even six-month supplies of their daily ARV drugs, instead of the usual one-month supply.

Taking the town of Khayelitsha, South Africa as an example, Doctors Without Borders piloted the adherence clubs model. Under this approach, patients, led by a lay worker, gather once every two months at the health facility or at a community venue, for ARV distribution. The group allows for peer support and health education among its members. Patients visit the health facility once a year for a clinical consultation and a viral load test. The model is being further expanded within the community, and adherence clubs are being organised in patient's homes instead of at a health centre. This model is well adapted to urban environments, especially where time spent at the clinic is an issue for patients.

Today, even in the resource limited areas, or conflict affected areas, a person who tests positive for HIV is offered counselling and started on treatment immediately.

CLINICAL GUIDELINES – 1980s

The most familiar problem has been and still is finding the resources Doctors Without Borders needed to practice medicine in places where everything was limited. This was particularly in refugee camps and remote areas, where everything had to be built from scratch.

Challenge: Large numbers of patients and a high turnover of medical personnel

Doctors Without Borders was and is often faced with large numbers of patients from poor communities facing significant physical threats. This was combined with a high turnover of medical personnel, most of whom had no experience with the tropical diseases they now had to learn how to treat.

The usual medical hierarchies would not necessarily be reproduced in the field. Because practical experience in these regions was the main qualification for the success of these missions, young physicians could exercise responsibilities that would normally be performed by department heads in their own countries, and nurses could take over the medical management of a mission. They needed as much help as possible from a text that was adapted to these emergency conditions.

So the Doctors Without Borders clinical guidelines were born out of the organization's mission to provide the best medical care it can during crises and their aim was to streamline the management of issues in the field and to standardize medical practices.

Adaptation: Develop scientific evidence based medical guidelines to standardise medical practices

In the early 1980s, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) drafted an emergency medical guide in Thailand. Oxfam designed a nutritional kit. Doctors Without Borders teams revised the texts based on their own experience to anticipate responses to a range of situations in which it would be used. This became the Clinical Guidelines.

The Clinical Guidelines were called the "green guide," after the colour of its cover. It was expanded and revised by its users.

Later, a guide to essential drugs was added to the green guide. It was designed for doctors unfamiliar with tropical environments, for nurses, and for national doctors working with Doctors Without Borders.

The introduction to the current edition explains:

Doctors Without Borders has been producing medical guidelines based on scientific evidence and lessons from our work in the field. The guidelines are the collaborative work of a number of experienced medical practitioners and specialists, and were developed for non-specialised medical staff. Data sources include the World Health Organization (WHO) and other internationally recognised medical institutions, as well as medical and scientific journals.The guides are designed for use by medical professionals involved in curative care at the dispensary and primary hospital. At the outset, the guides met the need for streamlining operations management, but they also sought to standardize medical practices. They take into account what may be basic technical environments in terms of diagnostic equipment, as well as restricted therapeutic means. They can be used as a basis for medical staff training.

Adapting to the digital era

In 2017, Doctors Without Borders launched the Medical Guidelines mobile app for iOS and Android, together with a website. The app functions as a locally stored mobile reference, which is available offline. It contains all the contents of the Doctors Without Borders Clinical Guidelines and Essential Drugs manuals, and contact information for all Doctors Without Borders offices around the world. In addition, the app can be accessed at any time on a variety of mobile devices, and has the ability to be updated instantaneously.